Welcome to the Transfeminine Review!

We’re so glad you’re interested in learning more about the history of transfeminine literature. Before we get started, I wanted to give an overview of the goals of this project, as well as a broad outline of what this first essay is going to cover.

My name is Bethany Karsten. I’m a trans woman and the editor of this blog, and I’ll be your primary guide as we explore this largely-uncharted field together. The Transfeminine Review is a blog dedicated to documenting and exploring the history and development of transfeminine literature, paying special attention to unique themes and tropes in the works of transfeminine writers, as well as the social, economic, and legal conditions of their production. My grounding for this project comes from a mix of formal education in English, Trans Studies, Philosophy, and Sociology; I am particularly interested in the philosophy of art – why we tell stories in the way we do, what aesthetic qualities produce excellent fiction, how our work speaks to deeper truths about trans life and the world around us – and the sociology of art – how works of literature arise out of the economic conditions of the artist, and how transfeminine writers reproduce those material conditions of production through their work. In this sense, The Transfeminine Review is often less interested in what a book has to say than how it says, which underscores our inquiry about why those ideas manifest as such in the first place. Our understanding of transfeminine literature is grounded in a historical and developmental analysis of the field and employs a multi-disciplinary approach to our work to best capture the nuance and multiplicity which has always defined genderqueer life.

Our primary inspiration is complicated, as this blog flies in the definitional face of it. In her 2020 manifesto Essays Against Publishing, Latina trans woman, community organizer, and founder of the Trans Women Writers Collective Jamie Berrout develops the concept of the anti-press, “a form of mutual aid that is organized around the production of writing by writers and readers working collectively for their survival and a total abolition of hierarchies.”1 Berrout writes:

The anti-press is what happens when writers and readers who have no credentials, no authority, and no power decide to take matters into their own hands and simply help each other do the writing they’ve wanted to do and release it in such a way that sustains their lives, wounds the state by rejecting its hierarchies and organizing myths, and fosters connections with others like them which also brings the moment of liberation a step closer. […] The anti-press forms among people with nothing, people practically living below ground, in and out of underground economies. Writers and editors who don’t have nothing are free to organize themselves in different ways—by definition they have the resources for it—but their work wouldn’t be the anti-press because they’d have a different relationship to the people with nothing the anti-press would call them to collaborate with.2

As a rich white trans woman, I want to be very upfront about the fact that I do have credentials, authority, and power. I am fully aware of the privilege that allows me to create this project in the form that you’re reading it in. What I share with Jamie Berrout is a core commitment to challenging the hierarchies and organizing myths of trans publishing, as well as an earnest wish to improve the situation of trans women and transfemmes within the publishing industry. Berrout’s work changed my perspective on what it means to be a trans woman writer, and though my attempts will surely fall short, it is my hope that I can take up the torch on her ideals of abolition and equal access to the press with half of the amount of passion that she embodied and spread those ideas to the trans women writers who need them the most.

This essay will cover the scope, methodologies, and purpose of this blog. We will examine the small body of literary scholarship of transfeminine fiction that already exists. My goal is to highlight predominant myths around trans women in publishing, demonstrating how they may fail to accurately capture the complexity of books of trans woman writers. We will cover the scholarship of Sandy Stone, Mckenzie Wark (author of Reverse Cowboy), Trish Salah (author of Wanting in Arabic), and Jamie Berrout (author of Otros valles), among others. Apart from Stone, all four of these authors are writers in their own right – at the present moment, there are no scholars of transfeminine fiction who study it as their primary discipline. This lack of dedicated secondary scholarship is part of the problem, and I will be critiquing that as well. We will discuss how current scholarship of transfeminine fiction has failed to address the textual object (as opposed to its symbolic or mythological role in the broader scope of trans liberation), as well as the common presumption that transfeminine fiction must necessarily be a progressive or radical force. We will explain why this project focuses only on transfeminine authors, and pose important questions about how and why we discuss the works we do.

A Brief Overview of Transfeminine Literary Criticism

Trans people have only recently begun to gain human rights or basic social dignity in modern society, and it’s no secret that those gains are hardly equally distributed. Around the world, the fight for trans liberation rages on, and one key battlegrounds is the fight for equal access to publishing and the freedom of the press. From book burnings in Nazi Germany at Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexology to the 1960 obscenity trial of Virginia Prince to the recent spate of book bans across the United States, trans literature has always been a fiercely contested battleground. The contours of the discrimination and ostracism which its authors have faced have shaped the genre as we know it today, as have the underground channels through which trans people in every era have sought to subvert it.

This is not to say that the trans battle for the freedom of the press is a unique struggle. In many ways, the past few decades echo publishing struggles from centuries past. The long history of enslaved, segregated, colonized, and apartheid-affected people’s struggle to have their voices heard, the specter of discrimination still hanging over women in publishing, and the class issues inherent to the publishing industry all foretell the history of trans literature. Understanding “trans fiction” as a stable genre, much less one in isolation from other publishing struggles across modern history, is an error that encourages the belief that trans fiction as a genre “sprung from nothing,” so to speak, after the creation of Topside Press and the publication of Nevada in 2013 as a part of the broader “Transgender Tipping Point” mythos. While shared DNA exists across the fictions of transmasculine, transfeminine, and non-binary writers, it is often a by-product product of homogenization, gentrification, and the development of a cisheteronormative respectability politics for our literature. It is also far more accurate to claim a “trans memoir” or “trans non-fiction” genre than a “trans fiction” genre. In the current moment, “trans fiction” offers a palatable version of the various literary movements that proceeded it by lumping together all the writers under the “trans” umbrella. By doing so, the particularity of the historical threads which produced our literary movement have vanished from sight.

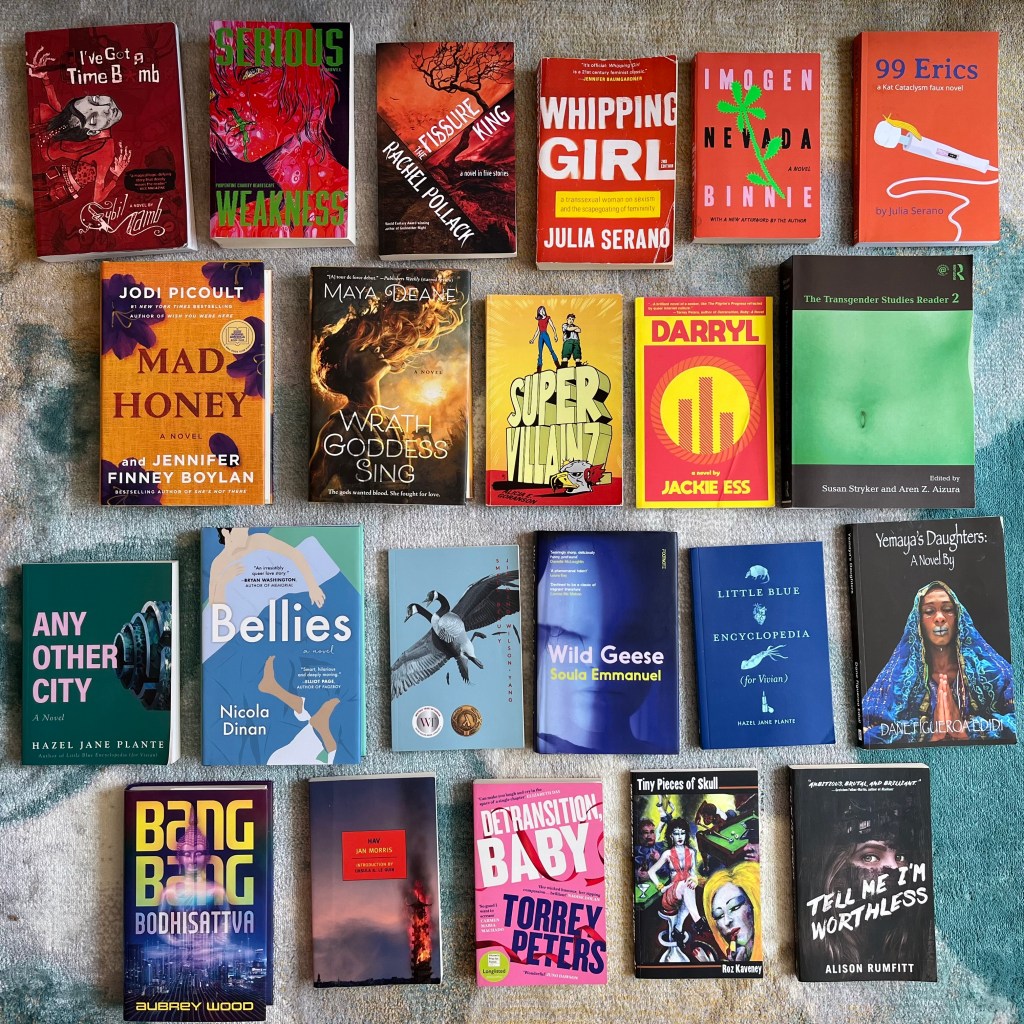

The methodological approach for this project, The Transfeminine Review, arises out of a survey of over 170 books by transfeminine-identified people spanning seven decades, and the researching and documentation of hundreds more. While influence from transmasculine and non-binary writers is clear in much of the literature after 2012, much of the literature written before the 2010s was produced in close-knit circles of transfeminine people living and surviving outside of co-ed activist circles. Moreover, even when produced alongside transmasc and enby writers, I have found that transfeminine literature tends to produce distinct themes and tropes that are unique to writers living under conditions of severe transmisogyny. While a survey of all trans literature would undoubtedly reveal “pan-trans” influences that precede Topside Press, it is my belief that a full accounting of the history and development of trans literature will be impossible until its various sub-groups and factional communities can be studied in all of their specificity and depth. My particular interests lay in the study of communities of trans women and femme-presenting AMAB non-binary people – those most affected by transmisogyny and transmisogynoir – and thus I have set out to chart here a possible course for what this form of inquiry looks like. Hence why this blog is called The Transfeminine Review, and why I will be speaking to only the experiences, texts, and scholarship of transfeminine writers for the rest of this essay.

While transfeminine scholarship has largely brushed off the notion of such a transsexual protogenesis, there still remains a second, more subtle mythology underlying how we discuss contemporary transfeminine fiction that holds that even if the production of transfeminine literature is not new, books like Nevada represent a emergence of a thematic literature that did not previously exist – was not allowed to exist – due to transphobia. Those with a passing familiarity of trans literature may have heard the “I’ve never heard a book talk about trans issues like Nevada” line before. Under this view, Topside Press is the beginning of an emergent but burgeoning minority literature, a view propagated from The New York Times to the New Yorker, and one which arguably arises from Sandy Stone’s scholarship in “The Empire Strikes Back: A Post-Transsexual Manifesto”, where Stone poses a cis-acceptable trans memoir industry against a silenced trans audience. She writes:

I am suggesting that in the transsexual’s erased history we can find a story disruptive to the accepted discourses of gender, which originates from within the gender minority itself and which can make common cause with other oppositional discourses. But the transsexual currently occupies a position which is nowhere, which is outside the binary oppositions of gendered discourse. For a transsexual, as a transsexual, to generate a true, effective and representational counterdiscourse is to speak from outside the boundaries of gender, beyond the constructed oppositional nodes which have been predefined as the only positions from which discourse is possible. How, then, can the transsexual speak? If the transsexual were to speak, what would s/he say?3

In the search for keystone texts upon which to say, “Hey, look, trans people have things to say too!” trans scholarship hesitates to dispute such ideas about trans voices and trans liberation. But this is an incomplete approach for understanding the history of transfeminine literature, one that both silences the voices who spoke before trans indie presses became an economic vehicle for the pan-trans author and makes it significantly harder to analyze and dissect what transfeminine literature is actually saying, why it says it, how it says it, and most importantly, how those themes and ideas have a distinct historical development inseparable from the social economies which produced them. In this myth of “originality,” transfeminine literary scholarship has to this point largely exempted itself from literary analysis that demand this degree of historical rigor or inter-textual (and intersectional) analysis. One of the key arguments of this mythology presumes that transfeminine fiction arose not from historical transfeminine literatures by both trans and cis authors alike, but rather from the autobiographical genre of the trans memoir. This is not to say that the memoir has not had significant influence – it has – but in many cases it is posited that a transfeminine fiction acquires the majority if not all of its DNA from various non-fictional media. This is a view espoused from, among many other places, one of the only prominent scholars of contemporary transfeminine literary history, Mckenzie Wark, who offers us the following picture in her essay “Girls Like Us”:

At the trans-lit conference I hosted, you laid out for us how in wrestling with these tensions, trans writing passes through four stages, in a sort-of dialectic, driven by the contradiction between the marginality of our experience and the dominant cultural forms available to hold them.

In the first stage, an emerging trans-lit presents your experience as just a curiosity within a universal story of gender as cis people already understand it, without your story much modifying the universal. This is the genre of the trans memoir. […] Jan Morris’s Conundrum is a finely written example. The gender novel written by cis people often acquires our pain second-hand from this genre.In the second stage, your character is punky, transgressive, oppositional. Sandy Stone called this our counter-literature. From Jayne County’s Man Enough to Be a Woman to Kate Bornstein’s Gender Outlaw, these books try to negate the universality of cis gender norms, but at the risk of becoming their mirror image.

The third stage came with Imogen Binnie’s Nevada, and took the form of a string of sad trans girl novels, deeply interested in the particulars of your life among other girls like us, with as little interaction with the cis world as possible. In this intentionally minor literature, we neither conform to, nor oppose, the universality of cis gender. We live in a world of our own. Casey Plett’s Little Fish and Kai Cheng Thom’s Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars are very fine examples. […two more stages follow]4

Wark presents a picture of the development of transfeminine literature that proceeds from memoir (our lived experiences) to theory (assessments of those lived experiences) to fiction (interpretations of those assessments). It is a fairly compelling view, and one supported by most current narratives about transfeminine literature. I also believe that it is wrong. In many way, this narrative relies on the premise that “our” literature arises as a response to “their” literature, AKA the faceless transphobe, TERF, gender novel writer, or general malcontent who relishes in the schadenfreude of trans pain. Its critical flaws are outsourced to an oppositional dichotomy against the cisgender literary foil. Certainly there are examples which back this up – again, one of the most prominent purveyors of this mythology is Sandy Stone, as “The Empire Strikes Back” was written in response to transphobic personal attacks by Janice Raymond, the text which would go on to create the field of trans studies. With the majority of trans scholarship arising out of the trans studies context, scholars of contemporary transfeminine literature have, to this point, sought to apply the same methodological approach from trans studies to a literary application and understanding of transfeminine fiction. In many way, this work has almost resembled a copypasta of trans studies’ homework:

“Trans Studies Literature was created as a brave and defiant response by Sandy Stone Topside Press and Imogen Binnie to transphobic attacks by Janice Raymond Gender Novels and the old-fashioned transsexual medical interview memoir, and has since become the fertile ground for imagining new and unprecedented possibilities for trans people in academia publishing. For the first time, our stories are being told by us instead of cis academics writers.”

Or so the story goes, at least.

The most blunt critique of this unfortunate trend comes from trans critic Andrea Long Chu, who wrote in 2019:

[W]hat’s happening [in The Empire Strikes Back] is that Stone is, like most scholars of gender in the nineties (and the aughts, and our own decade), molding her object to fit her theory, which is not by coincidence the same as the then fashionable theory. In other words, the basic narratological form of the medical discourse—what Stone calls a “plausible history”—has in fact remained largely intact. All Stone’s done is switch out the original content of that history (disease, diagnosis, cure) for a different content, namely, the prevailing elements of gender theory in the nineties (performativity, disruption, transgression). In fact, she’s laying the groundwork for the long-standing intellectual move in which the trans person, just through the act of existing, becomes a kind of living incubator for other people’s theories of gender.5

It’s important to note that transfeminine fiction itself is not the target of this particular critique. The actual novels themselves are by and large telling genuine, heartfelt, and important stories about what it means to be transfemme in this world. What I’m seeking to bring into question here is how we analyze those stories. How do we write about transfeminine novels? Why are our books always “ground-breaking” or “provocative?” And more importantly, how do we understand these books as a corpus? Which books get the privilege of that conversation? The fault with the minority picture and the sui generis picture is that they are less concerned with the literary object and more concerned with the literary subject, less with the actual textuality of a novel and more with the role it plays in an activism context. As such, readings of transfeminine novels are often centered more around how they represent trans femmes in real life, as opposed to how they compare to other representations of trans femmes in fiction. There is almost a face-blindness to structure, development, and history of the actual books themselves. Moreover, in cases where transfeminine novels are assessed as textual objects of literary study, they are often treated as not possessing any unique characteristics or oddities that can’t be explained away using conventional literary criticism techniques. Transfeminine authors and novels tend to be shuffled into a broader trend of #ownvoices literature, which largely attempts to increase ‘representation’ by replicating traditional white cishet literary practices for marginalized communities, or else filed under a subheading of ‘queer literature’ or ‘trans literature’ to be left on the shelf. While this has not been an unproductive trend, I still find those cis-traditional pieces of literary scholarship to be surface-level examinations of transfeminine tropes and themes which struggle to pierce to the heart of why transfemme authors want to tell these stories, and why they don’t want to tell others.

This trend of assessing transfeminine literature on the basis of either its verisimilitude/social commentary or its legibility for cis-conventional criticism is reflected in the work of another trans literary scholar, Trish Salah, who forwards a better (but still flawed) theory than Wark. Before critiquing her work, I want to first appreciate that Salah echoes and inspires many of the arguments I’m making here about the limitations of the minority picture of transfeminine literature. She writes:

As I’ve mentioned, from the 1950s to the 1990s, there were successive waves of intense cultural production by transsexual, transvestite, and transgender peoples […] [which] seem to disappear from view in the shadow of the outpouring of publishing during the second decade of this century. […] How then are trans literatures appearing in our time and place? If they appear as newly fashioned things, how are they made from what has disappeared from view? How might we think about emergence without producing either a national or a minority canon? What and how do trans somatechnics, transsexual critique, which I would also describe as trans sex worker critique, and trans of color poetics speak to or through one another, engage or refuse minority discourse, contest or subvert the trans normative? […] Contemporary trans literature is both haunted by and working through these difficult histories. We have yet to fully know how this work exerts a contouring influence on what can be written as trans in the (contested) present.6

These are the right questions, and one of the goals of this blog is to explore them. It should be noted that Salah’s work in “Transgender and Transgenre Writing” attempts an overview, not an answer; nevertheless, it’s clear that she doesn’t have an answer yet when she immediately turns from this question to a three-page analysis of Nevada. Like I said earlier, this is a better picture than Wark’s, but there are three primary flaws with this approach. Firstly, Salah provides no real interrogation of the relationships between various communities under the umbrella of “trans fiction.” As a survey of the ‘genre,’ trans fiction as a whole is taken as a coalescing force which moves with some degree of commonality and purpose, which again is a decent enough assessment as long as you’re not trying to understand trans lit from before 2012. In this sense, Wark’s account of the historical specificity of transfeminine fiction is more successful.

Secondly, Salah’s analysis hinges upon the Deleuzean argument of a “minor literature,” positing the literary act of creation as an individual intrigue and a political force which acts in opposition and subversion to the dominant thread of a ‘major’ literature, i.e. a socially normative cis literature. The production of transfeminine fiction in this form, Salah argues:

[s]uggests that if trans genre writing is a minor literature, then it works to both problematize and collectivize enunciation, which is not to say that the literature is homogenous, but rather that it works ‘to express another possible community and to forge the means for another consciousness and another sensibility […] The opacity of trans as umbrella and analytic shields conversations that both divide and circulate between genderqueer, transgender, two spirit, intersex, non-binary, ftm and mtf transsexual communities. Beyond this opacity, a fractious and impossible collectivity/nonrepresentativeness marks the work of the minor against minoritarian becoming.7

This builds upon her earlier assertion that “thinking trans genres in a minor key means thinking such writing as simultaneously making an entry into the human and disrupting and reordering that genre of being.”8

Salah uses the argument to disrupt the emergent minority literature argument, but the mechanism of this disruption is not an explanation for the historical development of trans literature, but rather the suggestion that the individual concern of each novel as “indispensable, magnified” to the degree that it erupts and fractures existing literary trends and norms. Those individual breaks form the possible terrain for imagining new trans possibilities in fiction. This argument works decently for contemporary trans literature after Nevada, but it completely face-faults the moment you perform a comparative analysis across that historical dividing line.

More importantly, it skirts around the creeping possibility that Salah starts to acknowledge in this essay but can’t quite embrace, which is that post-Nevada trans literature isn’t quite as removed from what came before as trans authors like to claim. She makes the important observation that “we write literary histories that exclude out folk forms, our obscene, erotic, and illicit forms, our woodworked and transsexual writers, non-Anglo European and/or non-university educated writers, and/or nominate only worthy, canonical progenitors for the current moment of flourishing.”9 The minor literature argument presents a disunified and amorphous field, one defined more by difference than any literary commonality, and I would argue that this argument upholds this conception of the literary avant-garde as disconnected from the history of transfeminine literary production which came prior. Her argument of a ‘reordering of genre’ suggests that books like Nevada and Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars have some degree of merit in their assertions that they represent a stark and revolutionary departure from what came before.

And they do – I don’t contest that. But any approach to resolving these difficulties that stake its assertions upon the departure of individual texts (especially when considered apart from the material conditions of their production) from an imagined or mythologized literary norm will inevitably fail to articulate the actual norms, tropes, and genres which cause those texts to be produced as they are in the first place. Genres, much like genders, tend not to materialize out of thin air, quite contrary to an account of transsexualism that would posit the production of the ‘artificial’ or ‘new’ woman. Literary tropes are not simulacra; there might not be an original, but they are not copies of a non-existent ideal insomuch as embodiments of a powerful undercurrent which has never ceased to exist.

The far bigger problem with Trish Salah’s argument, however, is that it commits another fatal presumption common among Trans Studies theorists – the notion that trans literature is not just a progressive force, but rather tantamount to a radical one.

This is false.

Literature is and always has been a bastion of transfeminine conservatism. When I speak of a ‘transfeminine conservatism,’ note that I do not mean right-wing reactionary blowhards, but rather the strict preservation of social norms, ideas, and customs that have developed among transfeminine communities, specifically white transfeminine communities, over the past decades and centuries. This manifests as strict normativities around sex and gender (often coupled with deeply, deeply unhealthy expressions of sexuality and self-harm) which go unquestioned not just in white transfeminine literature, but also most published transfeminine literature. This conservatism produces a symbiosis between lived white transfeminine life and literary white transfeminine life, which has had a bleed-through effect across the medium that inevitably ends up impacting TWOC too. I have yet to see a literary analysis of transfeminine literature that engages with this reality. The closest a scholar has come to a real honest engagement with this idea has been, once again, Andrea Long Chu, whose article “Did Sissy Porn Make Me Trans?” brushes upon the topic:

What it means, rather, is that in sissy porn, heterosexuality, especially in its coercive forms, is not a sexual orientation so much as an aesthetic form calibrated to reflect the basic heteronomy of desire—that is, the fact of desire’s originating outside of the subject. From this perspective—desire’s perspective—everyone’s a bottom, and not the politically reparable kind. The political lesson of sissy porn is this: Being trans can feel like getting fucked. There are, I like to say, at least two kinds of trans people: people who are trans because they want to be trans, and people who are trans because they don’t want to be trans. Sometimes these are the same people. But it’s this second mode of desire—where transness is, paradoxically, often tragically, constituted by a desire not to be trans, or by (we could say) a desire’s desire not to exist—to which sissy porn is designed to appeal. Hence the voice in which the sissy caption speak: anonymous, all-caps, and thick with authority. Desire is talking. It says to bend over.10

The transfeminine literary avant-garde have sworn off TG/TF (Transgender/Transformation) fiction, erotica, and sissy porn as ‘not representative’ of what trans fiction is and can be, but I think it is absolutely undeniable if you have read even a small amount of transfeminine literature that “being trans can feel like getting fucked” is not an uncommon refrain in the published books by trans women that get talked about the most. Whether it’s James in his AGP rabbithole in Nevada or Reese playing her disrespectful ‘AIDS Cowboy’ game in the beginning of Detransition, Baby, it is a nigh omnipresent theme. All of this amounts to a very important idea that Chu also touches upon in the introduction to this essay: “This work I’m sharing with you today is part of a larger project called Bad Politics. By bad politics, I mean what happens when subjects living under oppression just don’t feel like resisting that oppression and do something else instead.”11 Positing transfeminine literature as an inherently minor literature, or even as a literature which has recently taken on minor characteristics, underwrites and subverts our ability to have a real academic conversation about bad politics in transfeminine literature and how the themes, genres, and tropes represent a historical trend that has both material and political causes. And make no mistake, there’s a lot of bad politics in transfeminine fiction. For every book by a transfemme author that offers a radical or systemic critique of trans life, there are at least ten that uphold systems of domination, marginalization, and alienation within transfeminine communities. Perhaps this should be common sense – trans literature is no exception to Sturgeon’s Law. But if academic literary scholarship can’t adapt to the fact that A) transfeminine fiction is a Thing, and it has been for a decade if not a century, and that B) we are long past the stage where it is productive to praise books merely for existing, and that C) a failure to offer any meaningful critique or analysis of trans literary themes, tropes, and genres fails the entire trans publishing industry, not just trans academia – then transfeminine fiction will continue as always: undertheorized, underdocumented, and all too soon forgotten.

Or, more accurately: a small cadre of authors will successfully assimilate into the petit bourgeois of the trans/queer literary establishment, and an even smaller group into the cis literary establishment, and an entire domain of transfeminine history will be overwritten by a milquetoast, whitewashed, cisnormative accounting of how we got here and why our books read the way they do.

I think that would be a tremendous loss for the entire trans community.

Perhaps it should not surprise us (given that these mythologies are overwhelmingly predominant within indie trans publishing circles) that most of the transfeminine literary scholarship adequately addressing the shortcomings of the trans literary movement of the 2010s has come from the absolute margins of the field of trans publishing. Among the most important (and least recognized) of the 2010s critics of contemporary transfeminine literature is Jamie Berrout, the primary organizer and editor of the Trans Women Writers Collective. Printed in her 2015 collection Incomplete Short Stories and Essays but presumably written earlier, she wrote one of the only sustained contemporary critical accounts of this period of trans literary ’emergence’ that both Wark and Salah have attempted to retroactively theorize. When discussing The Collection, Topside Press’ first book, Berrout writes about watching the production of these mythologies in real time:

The Collection is, well, a collection of short stories about trans people – though, they’re not necessarily written by trans people – published by Topside Press. In an article in Original Plumbing (undated but I’d guess it’s from 2011), white trans man writer/editor Tom Leger lamented the lack of recognition that trans writers face in comparison to the cis writers who make a mockery of or perpetuate stereotypes about us, especially in the arena of the Lambda Literary awards. The article ends with a big pitch – Leger tells us that there’s hope in the form of a new trans book publisher that he (pronouns unsure) was starting up. That publisher is Topside Press. Interestingly enough, despite Leger’s great concern for trans writers, it seems that trans people of color are all but absent from this collection of trans stories. Now, what does that mean for the content of the book? What does that mean for a trans woman of color who picks up the book? […]

It was early in my transition and I had been searching for trans books that I might find myself in, yet I had only come across books about white trans people. And then I found The Collection –

it seemed as if, through the long list of authors in the book, I would finally see stories that reflected my own. But after reading a handful of the first stories I felt troubled. Why weren’t there more stories about people of color or more authors of color? […] As I pulled up name after name, the search engine showed one white face after another; many with graduate degrees, many with first novels already published; it seemed there was only one author of color in the entire book.I was confused. I asked myself, If there are so many white trans people getting books and comics published, if there are so many of them getting money and recognition and social support from their writing, why are there so few trans people of color who can say the same? Why does The Collection treat race and ethnicity like things that are outside the scope of the book, beyond reflection or concern, when racial disparities within the book are so stark?12

While there have been significantly more inroads for trans women of color in publishing since this essay was produced, race and ethnicity are hardly the only major issues to have been sidelined by the trans indie publishing boom. Class, ability, and nationality are also often neglected. There emerges a ‘default’ image of the trans author – a well-educated but lower-class able-bodied AngloCanadiAmerican trans person of ambiguous gender and sexuality, probably White or Asian, who had a tough past but has finally found success now that trans literature has arrived as a vehicle for her long-deserved success.

My aim in pushing this argument is not, to be clear, to bandy about accusations or suggest that progress has not been made. Rather, what I want to pose is that as the situation has improved for the trans author, the trans editor, and even the trans reader, a peculiar cultural amnesia has settled upon the field, one which fiercely resists attempts to connect our new ‘progressive’ literary present to an old ‘regressive’ literary past. Old authors and texts are obliviated from memory – in this overwhelmingly presentist discourse, trans literature acts as a standard-bearing force for an imagined contribution to trans liberation or something of the like. This is partially the fault of a tremendous and recurring generational gap within the trans community, where any representation of “trans identity” that doesn’t conform to the contemporary norm of transition – be it ‘transgender,’ ‘transsexual,’ ‘transvestite,’ ‘street queen,’ ‘sexual invert,’ or even more outdated language – gets erased and pushed out of our media in favor of whatever gender identifier is most favorable in the moment. What ensues is a total disconnect between our understandings of 21st and 20th century transfeminine fiction, a disconnect that neither accurately represents the history of the genre nor facilitates progressive motion toward a better situation for the marginalized transfemme writer in the future. While this amnesia is not entirely unusual for literary criticism – certainly not every mystery book or romance from a century ago is remembered – its pronouncement in the trans community remains both unusual and extreme.

It must be emphasized that this cultural amnesia is not some innocent oversight or a victimless quirk of the trans literary community. The writers who get erased from transfeminine history are almost always those most marginalized among us. I have been doing this research for over a year and a half now, and I can’t express to you how many times I have stumbled upon the works of a trans woman of color, only to discover that she is already dead. It’s exhausting to discover a new author, get really excited about her work, only to discover that either she was murdered or killed herself or simply just inexplicably disappeared, and that nobody even noticed. It’s exhausting.

It’s so fucking exhausting.

And look, I’m a white American trans woman. I’m rich enough to buy hundreds of books. I have a college degree. I had accepting parents and a good childhood. I am lucky.

But the transfeminine authors who aren’t?

They’re the ones whose work we simply allow to disappear. And that’s pretty fucked up if you ask me.

Books by trans women disappear all the time. The preservation of transfeminine literature should be a major issue within the community, and yet almost nobody talks about it, mostly because they had no idea those books existed in the first place. Sometimes this is because of a lack of access. Sometimes it’s because people never bothered to look. Usually it’s both.

Or as Berrout puts it in her 2020 work Essays Against Publishing:

What I want to say to trans women writers is that we’re no different. Because we lose sight of the ways that our work is formed out of and furthers colonization. We forget the ways all of this is bound together: how trans womanhood (the picture of a trans woman; who is seen and allowed to be one) is constructed out of race/racism, which itself also constructs colonial gender; how Trans Literature has been and continues to be a white supremacist project, which is also colonization, also gender; how publishing is built on the capitalist logic of merit, hierarchies of worth and superiority, which are also constitutive of the colony, of gender.

Publishing after all is a culture of death. It is rooted in the fascist notion that there are people who deserve to write and those who don’t; that it is good and well for editors to determine who gets to write and be published based on a writer’s proximity to whiteness, their social class and level of education, their ability (in contrast to disability; ableism too is fundamental to publishing) to overwork themselves and create a nice product that fits into their capitalist model, and their willingness to perform literariness and craft, all of which are arbitrary, racist ways

of determining what is proper and what is improper, human and less than human.13

Once you’ve sat with arguments like these for a bit, it puts Trish Salah’s argument that trans literature is a minor literature because it ‘challenges the boundaries of what it means to be human’ into perspective.

Where do we go from here?

From where I am sitting, it is undeniable that contemporary transfeminine literary scholarship is lagging at least ten years behind transfeminine literary production, and that in this vacuum of rigorous criticism, scholarship, or secondary infrastructure designed to assess the field of transfeminine publishing, important details about literary history have been falling through the cracks at an abominable rate. This is not an unpredictable problem. It takes time to train good academics, and I am likely at the very earliest edge of people who grew up with trans books. I was reading trans YA fiction from Meredith Russo and Zoe Taylor at fifteen in 2017. Simply put, that would have been an impossibility five years earlier, or at the least, a severely limiting project scarce on nuanced books to spark a genuine passion in the discipline. It’s now seven years later, and I’ve only just graduated from college, where I was in, once again, a fractional percentage of trans people who ever get the luxury of formal education from another trans person at any level of schooling, forget college. I had two trans profs in college, a trans man and and trans woman, one whom was Black. My high school debate coach was non-binary. At least four of my teachers besides the trans folks at various grade levels going all the way back to middle school have been openly gay. I can’t emphasize enough how rare and unprecedented it is to get that much queer education. It would take me at least four to five more years to get a PhD in English, after which point I would likely still need to find a faculty job for my publications to be taken seriously. The reason you are reading this now instead of in five years, or maybe never, is because I have disposable income, and by sheer lottery of birth, happened to have a particular set of interests that made me passionate about the issue.

So any potential scholars on the subject are at the beginning of their careers and probably can’t afford the books yet. When they do have the money to acquire books, they will likely spend it on the same set of fifty-odd books that have been published by the indie press circuit over the last decade first, as those are the books which already have critical engagement, or whichever critically acclaimed books happen to get publicity and buzz during the 2020s. With no scholarship to build upon, it will become progressively more and more difficult to backdate the history of transfeminine literature, and the production of secondary literature about those fifty books will turn into reproduction, and what now remains a threatening but fragile mythology will increasingly become a concrete narrative, a written gospel in the annals of trans history. That’s not to say that there won’t eventually be a better assessment of transfeminine literary history from the beginning of the 20th century to Nevada. But we are better equipped right now to assess, document, and critically dissect the development of contemporary trans literature than we will be at any point in the future. Data decays, books disappear, trans elders die. Transfeminine academia should strike while the iron is hot.

The Transfeminine Review is my personal attempt to bridge that gap and produce as much raw data and scholarship about books from poor, marginalized, POC, sex-working, self-published transfemmes as I can, with the ultimate aim of contributing to a better understanding of the history and development of transfeminine literature. It is entirely likely that my efforts will be unsuccessful, and that in the process of trying, I will add my own shortcomings and faults to the conversation. But at least there’ll be somebody on the internet trying. Hopefully my work here will inspire people who can do it far more competently and accurately than me.

The goals of this website are multi-faceted, so expect a decent variety of criticism, journalism, review work, interviews, and other various literary activities. I am acutely aware at how spare the field is when it comes to this material – my hope is never to be the only person doing this kind of work, but rather to simply be the first, or one of them.

This is a call to action for the transfeminine literary community – a call to remember our history, lest in its absence we be doomed to repeat it.

We wrote a follow-up to this essay entitled “How ‘Trans as Method’ Litcrit Fails Transfeminine Authors” and you can read it here.

- Berrout, Jamie and Bess, Isobel. Essays Against Publishing. Self-Published, 2020. 38. ↩︎

- Ibid, 38. ↩︎

- Stone, Sandy. “The Empire Strikes Back: A Post-Transsexual Manifesto.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 230. ↩︎

- Wark, McKenzie. “Girls Like Us.” The White Review, December 2020. ↩︎

- Chu, Andrea Long and Drager, Emmett Harsin. “After Trans Studies.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 6, no. 1 (2019). 110. ↩︎

- Salah, Trish. “Transgender and Transgenre Writing.” In The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First Century American Fiction, edited by Joshua L. Miller. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. 187-188. ↩︎

- Ibid, 182. ↩︎

- 178. ↩︎

- 186. ↩︎

- Chu, Andrea Long. “Did Sissy Porn Make Me Trans?” Self-Published, 2018. 10. ↩︎

- Ibid, 1. ↩︎

- Berrout, Jamie. Incomplete Short Stories and Essays. Self-Published, 2015. 150, 162. ↩︎

- Berrout, Essays Against Publishing. 5-6. ↩︎

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.