Introduction1

The history of contemporary transfeminine literature is defined more than anything by a sheer dearth of information. Before I attempt to make a single statement of historical fact, I want to emphasize that, then again so my reader understands: the history of contemporary transfeminine literature is defined more than anything by a sheer dearth of information.

I want to be clear that I mean a lack of published information. There is a lack of archival work, a lack of communication, and perhaps more than anything else, a persistent instinct (not one without warrant) that transfeminine literature must remain in obscurity. Knowledge about transfeminine literary history is often tucked away on obscure websites, or shared amongst friends in close circles of confidantes. Given the unreliable nature of trans kinship – trans women rarely have children to keep their histories, and any families of choice are contingent upon the continued survival of their communities in every sense of the word – when a trans person dies, specialized knowledge is often lost with them.

What is the purpose of this series? This is not a concrete theory, nor am I making any claims to absolute truth or complete information. What I want to present to you today is a sketch of what an account of transfeminine literary history might look like. There are years of archival work, interviews, research, reading, and study that will need to occur before anyone can claim to have an accurate picture of the development of transfeminine fiction as it emerged over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries – not in the least because the field seems uncertain that such a literary history exists in the first place.

Needless to say, if anyone has access to information that challenges, deepens, or adds nuance to any of the scholarship in this article, please don’t hesitate to comment below or email me at thetransfemininereview@gmail.com.

Over the course of my research, I have been able to identify a number of key figures in history who have made material contributions to trans literature in ways that are still visible today. Most of them, especially before the 20th Century, were cis men whose impact upon this field is incidental at best. I have done a great deal of research to try and deepen my understanding of those figures and their work. What I am less confident in, however, are my assessments of the interconnections between those various figures and communities. Please bear this in mind while you’re reading this.

As always, I hope that this is not the end of the conversation but the beginning of one. I’ve pieced this account together with sweat, duct tape, and not a small amount of spite, and I know that in the future, there will be scholars who will be able to produce much better scholarship on the subject than me. If that’s already occurred, you should probably go read that instead.

While the trans autobiography is obviously important to this discourse, A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature is a series about trans fiction, and more specifically the transfeminine novel and its origins. We will discuss places where shortform fiction crops up – undeniably, this is the more common form of trans fiction across history. But our ultimate goal with this essay is to contextualize the trans novel in its contemporary form, i.e., as popularized by Topside Press, and to assess the developmental history of its themes, tropes, and ideas. I am also particularly interested in this history not from the storytelling side so much as the publishing side. A fabulous tale of genderqueer or cross-dressing shenanigans from 1913 may be of interest to a trans reader, but if it was written and disseminated in isolation from other trans communities and had no apparent influence beyond its immediate circle, it is not a useful reference point for this project. The hypothesis of this essay – this whole website, really – is that there exists a continuous (though perhaps not unbroken) history of trans publishing, AKA the economic activities by transfeminine individuals relating to the publication of literature, that extends at least to the 1800s, if not earlier, and that it was that submerged communal creative activity and knowledge that would eventually provide the loam out of which a full trans publishing industry was able to emerge in the 2010s. While I have found a significant amount of evidence that supports this, I don’t contest the possibility that I am completely wrong and talking out of my ass.

Consider these ten essays an experiment, then. Allow me to present my research and preliminary conclusions. Whether I have assembled a cogent narrative or the pieces of an unsolved puzzle – that much remains to be seen.

Some Important Definitions

Before we begin, I want to sketch out a broad outline of the literatures I’m going to be discussing. There are four broad bucket categories of ‘trans’ literature that I’m going to be discussing, so let’s take a moment to address each:

“Transfeminine Publishing” – A broad encompassing term for the various economic activities of transfeminine individuals relating to the production and publication of literature. Note that this does not exclusively refer to those we might call “trans” in our modern day, but also transvestite and cross-dresser literary movements from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which are essential components to understanding contemporary transfeminine literature.

Petticoat Punishment/Discipline – A genre of underground Victorian erotica primarily centering around a pre-BDSM usage of domestic clothing and labor, corsets, and various other feminine accoutrements to emasculate and discipline male family members, typically husbands or sons. The genre had its observable beginnings in England in the late 1880s, and would quickly spread across the Continent before being largely purged over the course of the war period. Though it would be mostly a historical genre by the 1960s (for reasons we will discuss), production of petticoat punishment literature has been continuous since its inception, and there is still an extremely niche but active market for it today.

TG/TF (Transgender/Transformation) Fiction AKA Transition Fantasy – There is a misconception that all TG/TF is porn. Not only is this not true, but it also belies the historical origins of TG/TF as a distinctly sanitized genre. It is more accurate to describe TG/TF fiction as a species of genre fiction or perhaps even speculative fiction. But we’ll talk more about the classification of TG/TF later. Though it has earlier roots, TG/TF emerged as a publishing force in the 1960s in the United States, and its production continues to this day.

Transsexual Publishing – If you’ve ever heard a historical accounting of ‘trans fiction’ in the 20th century, they’re probably talking about this genre. This includes your standard memoirs, yes, but what I’ll be discussing moreso are the seeds of a business model for the transsexual author beginning around the 1980s – how the memoir genre enabled it, and how it also constricted it.

Lost Literatures – The vast majority of transliterary production from the 20th century is, of course, lost. Most of it was destroyed. These fictions are the silent presence which moves beneath the surface of all this history – sex working literatures, TWOC literatures, genocided literatures. We’ll keep them in mind during our discussion.

Why Start Here?

Many literary histories do not begin until the first observable ‘text’ of their Canon. In the case of transfeminine literature, that first text is an 1893 work called Gyneocracy, which has been extensively documented by Peter Farrer, who was the foremost scholar on Petticoat Punishment literature. In our case, however, we will not arrive at this ‘Ur-text’ of the genre until Part Five of this series. Why?

This entire history orbits around an attempt to understand and contextualize the impact of a single figure in transfeminine literature. Virginia Prince is often heralded as a groundbreaking trans activist, a ‘transgender warrior’ as Leslie Feinberg put it, but the reality of her impact upon transfeminine culture is much murkier. In truth, Prince was a reactionary and a conservative, fiercely dedicated to her particular ideas about transness and transition, and often violently exclusionary of those who fell beyond those bounds. She is also potentially the most important transfeminine publisher of the 20th Century, as through her magazine Transvestia, she not only popularized a business model for the dissemination of TG/TF literature through mail order, but also played a pivotal role in the formulation and calcification of many transfeminine literary tropes that persist to this day.

Virginia Prince came into contact with Petticoat Punishment literature in the late 40s and early 50s through her relationship with Louise Lawrence, the most prominent trans activist of her time, who had been hired by Dr. Alfred Kinsey to document Petticoat Punishment literature as a part of a broader sexological project to study the transsexual of the time. While Prince would adopt much of this literature for circulation in her magazine, it was not without significant alterations to the tone, style, and conceptuality of much of the work. The product of this was a very particular strand of conservative white feminization literature that not only should be familiar to most transfemmes who grew up reading internet fiction, but also was a profound counter-influence on the trans publishing boom in the 2010s. The reason I have begun nearly 150 years before the first ‘transfeminine novel’ was published is because I want to understand not just the impacts of this conservative transfeminine literature of the second half of the 20th Century, but the political origins of that particular strand of trans conservatism as well, and why it seems to possess such a singular longevity and virulence within our literature.

Over the course of her career, Virginia Prince was beset by a variety of legal troubles and challenges to her work that significantly altered the shape and course of her writing, and the TG/TF genre as a whole. What I have discovered in my research is that, far from being disconnected from the struggles faced by the “street queen” or everyday transsexual of the time, it arises out of a greater system of discrimination that has implicated publishing as one of its primary aims from the very beginning. The first four articles in this series are thus dedicated to sketching out the legal and political histories that would eventually shape this literature, and extensively demonstrating how schisms in the trans publishing world from the 1960s to the 2010s are not new phenomena, but rather historical manifestations of these trends.

I would urge my trans readers to take these “cisgender” histories as seriously as they would an extensive discussion of an erotica pamphlet by a “male lady” in the 1720s. Though it is easy to dismiss a figure like William Wilberforce as irrelevant to our contemporary literature, an assessment of this history proves that he is anything but. Knowledge is power, and the nature of transliterary history has been left almost completely in the dark. It is my hope that over the coming weeks and months, I can provide a rigorous framework for future research, one that can become a baseline off which people can delve deeper into the specificity of the history I have discussed.

Additionally, definitions of “trans” identity will be continually changing over the course of this recounted history. Rather than trying to provide definitions at the beginning, I will instead say this: this is not a history of trans identity. It’s not even really a trans history. It’s just history. I am making no claims whatsoever to the historical identities of these individuals. Rather, what I aim to present here is an explanation for a particular form of literature as a historically grounded phenomenon shaped by its circumstances; its transness is merely incidental. This is not a “history of trans literature,” but a history of how we arrived at a thing called “trans literature” in all of its various implications.

So if this isn’t a story about trans literature, or at least not entirely, then what is it? First and foremost, this is a story about the power of publishing – and perhaps more importantly, who has the power to publish. It’s a story about how the personal foibles of individual men can have life-shattering effects on the lives of marginalized people centuries in their wake. It’s a story about social conservatism within progressive movements, how even prominent activists can be responsible for some of our more reprehensible ideas. And it is perhaps also a story about the fractiousness of trans history, and how unexpected and downright bizarre the origins of our stories can be.

The discrimination against trans people in the publishing industry was so severe that, until the 1980s, we have zero examples of novels by openly transfeminine authors getting traditionally published. The reason behind this comes down to a very complicated knot of legal issues surrounding cross-dressing, obscenity, licentious literatures, sedition, and a variety of segregationist, nativist, and evangelizing pursuits. These first four essays are dedicated to picking that knot apart, understanding how they affected trans publishing, and laying the groundwork for an understanding of how 21st Century transfeminine publishing has – and hasn’t – made progress against those institutionalized discriminations.

Or, as my editor Korra succinctly put it: “Obscenity law is how basically all out-groups are targeted. It’s the final piece of a puzzle, a formalization of social attitudes.”

We begin our story at least a century earlier than most people would expect…

The Moral Origins of Obscenity

“God Almighty has set before me two great objects: the suppression of the slave trade and the reformation of manners.”

– William Wilberforce, October 28th, 17872

The first thing that you need to know about William Wilberforce is that he does not map cleanly onto any contemporary metric or evaluative compass of “political morality.” By the standards of our time, he is too progressive to be conservative; too conservative to be progressive; too monarchist to be a liberal; and above all, entirely too influential in the course of world history to be distilled down to any such terms. But his particular brand of moral crusading, which was deeply informed by his evangelical heritage, may come across as all-too-familiar to the modern day transsexual. To this day, Wilberforce remains a figure célèbre in Evangelical history circles – and who could blame them? A hardcore evangelist who happens to be one of the most important figures in the abolition of British slavery? The marketing pitch writes itself.

William Wilberforce was born in Yorkshire in 1759 to a life of extraordinary wealth and privilege. As a child living with his aunt and uncle, he was inducted into the Evangelical faith, while also coming into contact with John Newton, who wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace” and had previously reformed from a slave trader to a true abolitionist. Though his mother would take him back in and attempt to disabuse him of his evangelism, her efforts would ultimately be unsuccessful. While I would consider it an unreliable source for just about anything else, The Wilberforce School in Princeton, New Jersey offers us a compelling description of Wilberforce’s rediscovery and commitment to his evangelism on their website:

In 1784, while respected as one of Parliament’s leading debaters, Wilberforce decided on a European tour and invited an Irish friend to accompany him. When the friend declined, Wilberforce asked Isaac Milner, the brother of Joseph Milner (his former schoolmaster) to join him. Isaac, an Anglican clergyman, was known as a brilliant Cambridge scientist and mathematician. Unaware of Milner’s evangelical convictions, Wilberforce was surprised to find that someone whom he could respect intellectually could also embrace a Christian worldview. Together they read and reviewed the Greek New Testament and Philip Doddridge’s The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul. By the end of two European trips, the politician was convicted of his sin. He acknowledged “a sense of my great sinfulness in having so long neglected the unspeakable mercies of my God and Savior.”4

I want to give you a sense of what an Evangelical picture of Wilberforce’s life looks like because it was introduced to me through a similarly rosy though rather more secular portrayal. My education about Wilberforce began in middle school, when my entire grade was made to read Bury the Chains by Adam Hochschild, then to watch the 2007 biopic Amazing Grace, which was based upon Wilberforce and Newton’s lives. I will note that Bury the Chains was a far better product than Amazing Grace, as Bury the Chains was also prominently the account of the life of Olaudah Equiano, one of the most important figures in Black history and a prominent architect of the end of chattel slavery in the Caribbean. I’ll also give my middle school credit – our unit was mostly dedicated to Equiano, not Wilberforce or Newton. Nevertheless, as an impressionable thirteen-year-old, I walked away with the impression of William Wilberforce as a titan of abolition, a remarkably progressive figure in the history of the Anglophone world and an early example of social justice to look up to.

Going back and rereading Bury the Chains, it’s not hard to see how I arrived at that impression:

Critics then and now have attacked Wilberforce for showing more pity for slaves than for suffering Britons. He was entirely faithful to his own view of the world – one divided into generous rich and grateful poor, into those wise enough to vote and those too unpropertied for the privilege, into Christians who knew God’s truth and heathens who did not. Nonetheless, to his credit, it was a world in which slavery ultimately had no place. Furthermore, although he supported harsh legislation against sin, to sinners he met personally he was the soul of kindness. He gave generously to charity; in one year of food shortages, he contributed far more than his own income. When he bought a piece of land with tenant farmers on it, he lowered the rents and never complained if people fell years behind in their payments. He frequently paid the bills of debtors he took a liking to, so they could get out of jail. He was so honest that he would not permit his servants to tell a visitor he wasn’t home if he was, and as a result his hospitality was always larger than his table.5

You could have told my middle school self that the man paved the streets of London’s filthiest slums with gold, and I probably would have believed you.

Modern historians, Christian primary schools, and soppy biopics about the role of Good Christian White Men in abolition are hardly the only culprits of this mythologization of Wilberforce’s life. As far as I can tell, William Wilberforce has been a saintlike figure in the Evangelical imagination for centuries, and I find that his resume as an abolitionist is often used to obscure the far murkier work he dedicated to the “reformation of manners.” It must be noted that a very significant amount of the modern historical record of Wilberforce’s life comes to us through a five-volume biography written by his two sons, which exhaustively chronicled the details of his life. I also want to emphasize that Wilberforce’s commitment to “moral reform” was no secondary objective in his life – his impact upon the matter was so great that historian M. J. D. Roberts began his account in his book Making English Morals with Wilberforce’s life work. This book also appears to be the source for many accounts of one of Wilberforce’s early-career accomplishments, which has been suggested as an inciting incident in the broader development of this shift in English morals:

Wilberforce had started at the top. Already, in the spring of 1787, he had successfully played on the susceptibilities of the archbishop of Canterbury and of Queen Charlotte in order to induce [King George III] in Privy Council to consent to a royal proclamation against vice and immorality. This proclamation was issued on 1 June and duly forwarded by the Secretary of State to county authorities. Its contents combined a general denunciation of moral decay with a particular call for the enforcement of existing laws against drunkness, gaming and profane, licentious or disorderly behavior.6

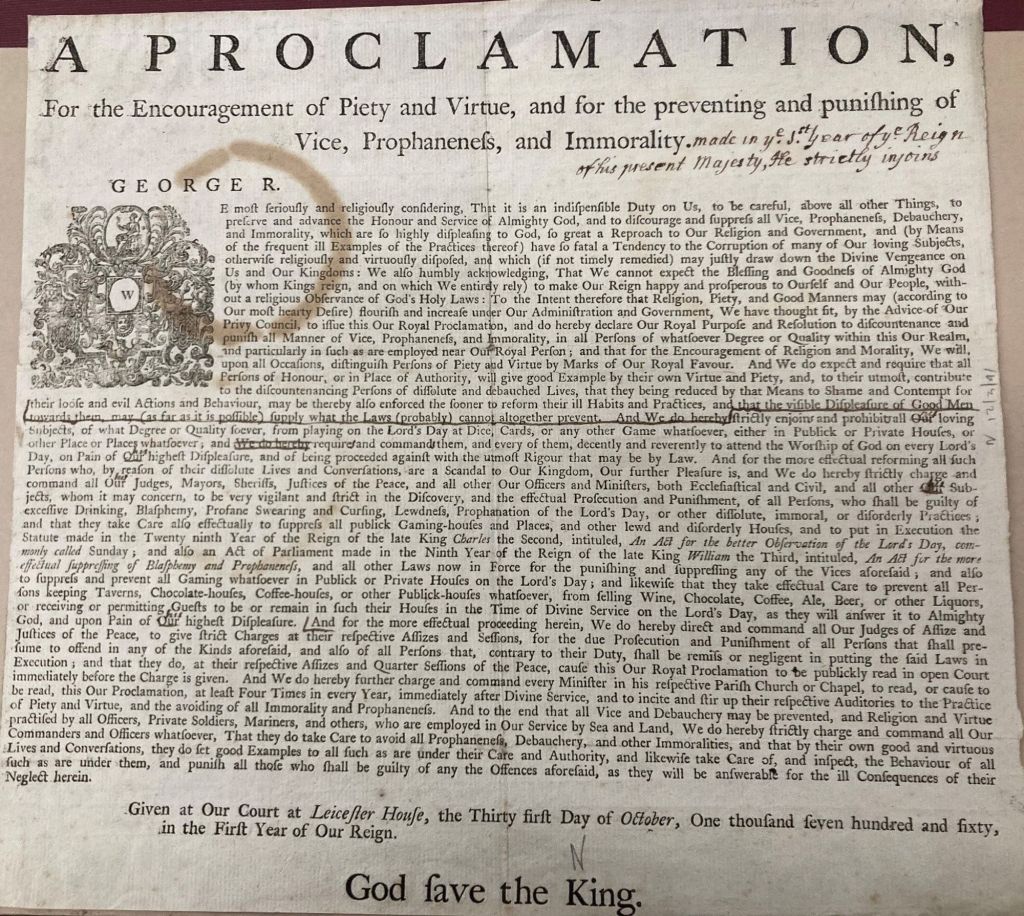

The way that this and many other sources present this is misleading. While it is true that Wilberforce popularized this document, known as the “Proclamation For the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing of Vice, Profaneness and Immorality,” various versions of it had been circulating within the British monarchy and its edicts since almost a century earlier during the reign of Queen Anne.7 While I wasn’t able to track down a full version of the 1787 proclamation, I was able to find the full text of a proclamation issued with the same title by King George III in 1760, which I will enclose an image of below for reference. This 1760 version is notable for two reasons. Firstly, it indicates that Wilberforce did not urge King George III to create a proclamation, but rather to adapt, update, and reissue a proclamation made in the first year of his reign. Secondly, this proclamation is notable because it played a small but significant role in the broader incitement of the American Revolution, as it was also republished prominently in the colonies:

Understanding this document in the context of the American Revolution will give us a very odd preview into a series of schisms in the development of transfeminine literature about two centuries later. I know that’s an absurd claim, but hear me out. For those who haven’t brushed up in their Revolutionary War history: King George III is most notorious for “losing the colonies” in the American Revolution, and perhaps best known to a contemporary American audience as the only white actor in any production of Lin Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton. He is a cartoonish villain to the American imagination and a complicated figure in British history, and it is the extreme complexity of this disconnect – and the abolition of slavery which would drive a schism between the social development of these two countries over the following decades – that will provide the social context that would eventually allow for the emergence and shape of the American TG/TF genre from its British Petticoat Punishment cousin.

While the 1760 declaration itself would be mostly forgotten to an American audience, it would find a second life in 1774 with one of the Revolutionary War’s greatest antagonists, the governor of Massachussetts Thomas Gage, who published an ill-advised parody of the Proclamation with Loyalist printer Margaret Draper. Gage’s popular policies included the enforcement of the Intolerable Acts, a series of four acts designed to punish the people of Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, including an ordinance that allowed the quartering of British troops in the homes of private citizens, AKA the reason we have the Third Amendment. The good people of Massachusetts were not particularly fond of this. This article, subsequently written in July of 1774, was an attempt to quell the unrest, and called for the colonists to “avoid all Hypocrisy, Sedition, and Licentiousness, and all other Immoralities.”10 While it did not come from George’s mouth himself, it’s important to understand that both the “Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue” and George’s reign as a whole are both inextricably tied to the loss of the United States, and the deep impact that it had upon the British psyche.

So there was a whole war over British tyranny, Britain lost, and the United States was born. The public shame of losing the American Revolutionary War (at the hands of the French no less, whom the British had been tussling with for dominance of the Americas for the better part of a century) was so great that King George seriously considered abdicating the throne on multiple occasions. Professor Arthur Burns provides us with an extremely important reading of George’s 1783 Abdication Speech, drafted but never delivered, which acknowledged the defeat but offered us a tantalizing set of other observations:

Such an understanding, however, did not preclude – indeed it necessitated – a clear understanding of the course of events which had led to this outcome. The speech very clearly sets out the analysis, both short and long-term, at which the king had arrived by March 1783. He was clear in his belief that, as he stated near the start of the speech, ‘Unanimity … must have rendered Britain invulnerable though attacked by the most powerful combinations’. Therefore the fact that it had proved only too vulnerable could be attributed to the absence among the governing political class of ‘the first of public Virtues, attachment to the Country’, this having been replaced by ‘selfish views’. This development in turn George attributed to the decline of a proper ‘sense of Religious and Moral Duties in this Kingdom’, to which ‘every Evil that has arisen owes its Source’. And here we see George placing the immediate context of the loss of America within a much longer timeframe, one bringing into consideration the whole history of the high politics of the nation since his accession in 1760 and indeed before. In particular, he located the actions of leading politicians in the cabinet crisis within a much broader interpretation of the actions of a political class who had collectively frustrated the ambitions which he had set out for himself as monarch on his accession, and indeed trespassed upon his royal prerogatives.12

This view within the British Monarchy held that an American immorality or licentiousness was one of the primary causes of the American Revolution. To compensate for the psychological loss of the British superiority in war, the British aristocracy attempted to reconstitute a moral superiority that might restore them to their rightful place as the foremost nation in the world. As so does Burns contextualize the reissuing of the Proclamation four years later in 1787: “Four years later George would issue a ‘Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing of Vice, Profaneness and Immorality’ which explicitly linked this to avoiding divine retribution on the nation as a whole.”13

It is important to observe that, while the Anti-Vice elements of this shift in British society are more relevant to our inquiry about transfeminine literature, many of these early censorship innovations were aimed at sedition and insurrection against the backdrop of the American and French Revolutions than licentiousness. The DNA of the Thermidorian Reaction, the conservative backlash in the wake of a social revolution, is going to be absolutely crucial to understanding the criminalization of obscenity and cross-dressing in the United States, so keep it in mind. On the Crown’s turn against insurrection in the 1790s, Naomi Wolf writes:

But that relative state tolerance for free speech would change. With the coming of the French Revolution, many radicals in Britain were inspired by the uprising across the Channel; activists such as Thomas Paine and Richard Price called for universal freedoms and for government by the people. So elite’s fears of domestic populism and of radical groups led to innovations in systematically crushing dissent. In one state crackdown, for instance, British dissidents were labeled ‘Jacobins’ and identified with terrorists, and press hysteria led to vigilante groups engaging in violence against them. In 1792, after having lost the American colonies, King George III issued a “Royal Proclamation against Seditious Writings.” A year later, William Pitt sent spies to infiltrate British activist groups in his “reign of terror.” In 1794, the government suspended habeas corpus law – and arrested activists who sought to flee. Then the ‘Gagging Acts’ were passed, which made it a crime to hold public meetings. Powerful tests of modern state controls of speech were essayed and proven out.14

So, we return to the work of William Wilberforce. Despite all of his faults, Wilberforce’s decision to link the import of abolitionism to this climate of desired moral superiority was a stroke of sheer genius. Remember that in 1787, the American Constitutional Convention was busy ripping itself nearly to pieces over the issue of slavery. The product of this was the three-fifths compromise, a deal that would allow each slave to be counted as “three-fifths of a person” in state censuses in order to artificially inflate the power of the vote of White Southerners in the new House of Representatives, as the Southern slaveholders knew that they would be outnumbered by their abolitionist Northerner counterparts otherwise. Even at the time, this decision sparked a moral outcry as one of the more blatantly unjust pieces of politicking in human history. In this moment of tumult in both Britain and America, Wilberforth lobbied the King to issue a renewed version of his 1760 edict, revised and updated to meet the moral needs of the present day.

While the majority of this document was merely a restatement of earlier edicts, there was one new addition to the record that will prove itself of the utmost consequence for the history of transfeminine literature:

The proclamation declared the royal intention to punish “all manner of vice, profaneness, and immorality,” forbade “playing on the Lord’s Day at dice, cards, or any other game whatsoever, either in public or private houses,” and commanded special energy in the enforcement of the laws against “excessive drinking, blasphemy, profane swearing or cursing, lewdness, profanation of the Lord’s Day, or other dissolute, immoral, or disorderly practices . . . public gaming-houses . . . unlicensed public shows, interludes, and places of entertainments . . . loose and licentious prints, books, and publications,” and the supplying of refreshments during the time of divine service. 1 But though the scope and wording of the proclamation reveals Wilberforce’s own preoccupation with the personal morals of his fellow-citizens, the Home Secretary’s covering letter lays stress upon “the depredations which have been committed in every part of the kingdom, and which have of late been carried to such an extent as to be even a disgrace to a civilised nation,” and urges action “for the preservation of the lives and properties of His Majesty’s subjects.” (emphasis mine)15

While I don’t know if this is the origin of these ideas, the 1787 “Proclamation For the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue” is the earliest document that I have been able to find that links together the banning and destruction of taboo, illicit, and erotic literatures with the modern project of nation-building in the wake of a perceived national humiliation. I want to emphasize that it is not the particularities of Revolutionary War history, but this connection of morality, nation, and book-banning that is the key historical factor to observe here.

So, what relevance does this have for understanding transfeminine literary history? We need to contextualize this within the history of genderqueer lives in Britain at the time.

The first important thing to know is that sodomy was a capital crime in the United Kingdom until 1828, meaning that it was punishable by death. There was also a shift in the definition of sodomy over the course of the 18th century:

In the 1600s and into the 1700s, the term “sodomite” applied to a practicioner of any form of non-reproductive sex, whether between members of the same sex or not. Despite the threat of the death penalty, sexual acts between adult males and adolescent males and females were commonplace and–during the 1600s–generally socially accepted. About 1700, gender lines and cultural expectations regarding sexual preferences became more rigid.16

In 1691, a new organization was founded called the Society for the Reformation of Manners, which had as its primary goal the banning of prostitution in the United Kingdom. One of the primary targets of their actions was the historical center of what we might now today call “queer subculture” in London, the molly house, a type of public house notorious for being a center for sodomites, prostitution, and public sex in urinals. In 1727, a preacher named Richard Smallbrooke condemning the molly houses for their sodomite practices, and celebrated the Society for the Reformation of Manners for their work in quelling them. He said:

Once more; since that most detestable and unnatural Sin of Sodomy, which but rarely appears in our Histories, and that among Monsters and Prodigies, has been of late transplanted from the hotter Climates to our more temperate Country, and has dared to shew its hideous Face among a People that formerly had it in the utmost Abhorrence; it is now become the indispensable Duty of the Magistrate to attack this horrible Monster in Morality, by a vigorous Execution of those good Laws, that have justly made that vile Sin a Capital Crime. […] On this Occasion therefore I think it my Duty to Congratulate those among us, that have the Courage to bear the Odium of a Virtuous Singularity in a degenerate Age, to appear on the Lord’s side, (as Moses expresses it, Exod. xxxii.26.) and to join the Sons of Levi in supporting the Cause of Religion, upon their late good Successes in this spiritual Warfare. It is no doubt a very pleasing Reflection at present, and will be an unspeakable Consolation in the last Moments of Life, of all good and active Magistrates, that they have used their Authority in supressing several lewd Houses, and infamous Nurseries of Debauchery; or in contributing to clear the Streets of their greatest Nuisances, the soliciting Night-walking Strumpets, those shameless Scandals of their Sex and Country. And that those abominable Wretches, that are guilty of the Unnatural Vice, have been frequently detected and brought to condign Justice, is very much owing to the laudable Diligence of the Societies for Reformation. . . .17

The next year, a molly house run by one Miss Muff, legally Jonathan Muff, was raided by the police. During this raid, nine “male ladies” would be arrested. A contemporary newspaper of the time, The Flying-Post, reported:

Jonathan alias Miss Muff, and nine Male Ladies were all apprehended last Sunday Night at his House in Black Lyon Yard near White Chapel Church, carried to New Prison, and examin’d next Day before a Magistrate, when J. Bleak Cawland charged on Oath with committing the detestable Sin of Sodomy, was committed to Newgate, another to Bridewell, and Miss Muff with the other six to Newgate: Two Persons were also catch’d in that horrid Act last Week at Redding; one of whom was immediately pump’d, thrown into a Bog-House, and then rinsed in stinking Ditches; what will come of the other Beast is not said.18

Despite their successes in tamping down on the molly houses, the Society for the Reformation of Manners would fall out of favor in the 1730s, and though sporadic attempts would be made at its reformation throughout the 18th Century, they would ultimately prove unsuccessful – that is, until one William Wilberforce made it his mission to pick up the legacy of their moral crusade in the 1780s and 1790s. At the time, England was undergoing a rapid increase in population due to industrialization, and a climate of urban decadency, wage gap, and extreme poverty had contributed to a widespread social malaise. In Making English Morals, Roberts writes:

A third measure of the unease aroused by unrestrained commercial growth is to be found in responses to the growth of a particular industry – that of publishing. If any one industry aroused anxiety about consumer frailty more widely than another, it was […] the publishing industry. The subversive potential of mass literacy had long been recognized in general terms, but the massive success of late eighteenth-century publishers in locating new markets for exploitation gave immediate and recurring reason to deplore the growing licentiousness of the press. In some degree this increased sensitivity may be seen as one facet of the general concern felt for the moral indiscipline of the lower orders. In some degree this increased sensitivity may be seen as one facet of the general concern felt for the moral indiscipline of the lower orders. […] By the mid-1790s, as we shall see, attitudes such as these were to be overlaid by explicit fears of political and social subversion – English Jacobins retailing French revolutionary ideas to the gullible English masses – and concern about the reading of the lower orders turned to panic.19

In the aftermath of the publication of the Proclamation in that November of 1787, Wilberforce would found the Proclamation Society Against Vice and Immorality, which was dedicated to combatting the forces observed in King George’s declaration, included but not limited to the licentiousness of the press. In 1802, this society would directly inspire the creation of the Society for the Suppression of Vice, which was a similar and far more influential organization which would operate until 1885. Against the bloody backdrop of the French Revolution and the aftermath of its American predecessor, the sex panic of the 1790s was seen as “a matter of national security.” Katherine Binhammer writes: “In linking sexuality to the health of the nation (regardless of whether that nation is imagined as Whig or Tory), social commentators claim that the state of the nation can be judged through the condition of the country’s morals and, by extension, through the manners of its women.”20

The primary object of this sexual panic was the role of women in English society, which would in many ways presage the role of women in the Regency Era, and as such most of the historical scholarship focuses on that. However, sodomy was also a primary concern, especially with the Society for the Suppression of Vice. In the document “Report of the committee of the Society for carrying into effect His Majesty’s proclamation against vice and immorality, for the year 1799,” the Proclamation Society establishes that these literatures were at the heart of their objectives moving forth into the 19th century. They wrote:

The publication of obscene books and prints is an offense which attracted the Society’s earliest attention, and to which as to an object of the first importance it has uniformly continued to direct its regard. At the same time, may be mentioned a crime analogous in its nature, which to a degree of great enormity has more than once occurred – that of indecent exhibitions of various sorts. It is unnecessary to enlarge on the mischievous effects of which these offenses are productive, especially to the morals of the rising generation; and to what an extend the contagion, particularly that of indecent publication, had diffused itself, may be inferred from the discovery, that, in addition to the other modes by which this moral poison had been infused into the circulation, there was good reason to believe that it had found its way into a female seminary of education.21

The pamphlet then proceeds to describe the case of “a young man in a very respectable situation” who was “suddenly hurried into the commission of a capital crime.”22 While I cannot confirm this (perhaps an archivist could), it seems very likely to me that this capital crime was that of sodomy, as it immediately goes on to propose the “regulation of public houses” and the “alteration of the Vagrant laws.”23

Thus William Wilberforce would enter the 19th century with the twin evils of slavery and poor morals fixed within his view.

This is Part One of a eleven-part series on the historical development of transfeminine literature. Part Two, “Trans-Atlantic Relations and the Obscene Publications Act of 1857,” can be read here.

A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature

- Part One: The Moral Origins of Obscenity

- Part Two: Trans-Atlantic Relations and the Obscene Publications Act of 1857

- Part Three: American Evangelicalism and the Ineptitude of the American Whig Party

- Part Four: The Birth of American Anti-Trans Law

- Part Five: Petticoat Punishment and the Comstock Act of 1873

- Part Six: Continental Erotica, Magnus Hirschfeld, and the Nazis

- Part Seven: Virginia Prince and the ‘Invention’ of the Transfeminine Press

- Part Eight: Jan Morris and the Conundrum of the Transsexual Author

- Part Nine: Transfeminine Publishing and the Digital Revolution

- Part Ten: Topside Press, Nevada, and the ‘Transgender Tipping Point’ Myth

- Part Eleven: Detransition, Baby, the Pandemic, and Transfeminine Publishing Today

Reading List

Primary Texts

- “By the Queen, a Proclamation, for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing Vice, Profaneness, and Immorality” – Queen Anne (1708)

- “Reformation Necessary to Prevent Our Ruin, 1727” – Rictor Norton (1727)

- “Jonathan alias Miss Muff, and nine Male Ladies were all apprehended last Sunday Night” – The Flying-Post (1728)

- “Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing of Vice, Profaneness and Immorality” – King George III (1760).

- “By the Honourable Thomas Fitch, Esq; Governor of His Majesty’s English colony of Connecticut, in New-England, in America, a proclamation. Whereas his Most Gracious Majesty, from a regard to the honour of God and a concern to promote religion” – Thomas Finch (1761).

- “Province of Massachusetts-Bay. By the Governor. A Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue…” – Thomas Gage (1774).

- “A Draft of a Message of Abdication from George III to the Parliament” – King George III (1783)

- “Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing of Vice, Profaneness and Immorality” – King George III (1787)

- “Royal Proclamation against Seditious Writings” – King George III (1792)

- Treason Act of 1795 (United Kingdom)

- Seditious Writings Act of 1795 (United Kingdom)

- “Report of the committee of the Society for carrying into effect His Majesty’s proclamation against vice and immorality, for the year 1799” – Society for Giving Effect to His Majesty’s Proclamation against Vice and Immorality (1800)

Secondary Texts

- The Life of William Wilberforce – Robert Isaac Wilberforce and Samuel Wilberforce (1838)

- History of Liquor Licensing in England Principally from 1700 to 1830 – Beatrice Potter Webb (1903)

- “The Sex Panic of the 1790s” – Katherine Binhammer (1996)

- Making English Morals: Voluntary Association and Moral Reform in England, 1787-1886 – M. J. D. Roberts (2004)

- Bury the Chains: Profits and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves – Adam Hochschild (2006)

- Amazing Grace – Michael Apted (2007)

- Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love – Naomi Wolf (2020)

- “George III: well-intentioned but faced with insurmountable problems” – Guildhall Library Blog (2022)

- “The Abdication Speech of King George III” – Arthur Burns (accessed 2024)

- “Homosexuality and the Law in England” – Douglas O. Linder (accessed 2024)

- COVER: Unknown, after John Collet. “A Morning Frolic, or the Transmutation of the Sexes.” Mezzotint. Date Unknown. https://collections.britishart.yale.edu/catalog/tms:30717 ↩︎

- Wilberforce, Robert Isaac, Wilberforce, Samuel. The Life of William Wilberforce, Volume One. 1838. 149. ↩︎

- Hickel, Anton. Portrait of William Wilberforce. 1794. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_wilberforce.jpg ↩︎

- “William Wilberforce.” The Wilberforce School. Accessed September 5th, 2024, https://www.wilberforceschool.org/updated-about-us/william-wilberforce ↩︎

- Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves. New York: Mariner Press, 2006. 314-315. ↩︎

- Roberts, M. J. D. Making English Morals: Voluntary Association and Moral Reform in England, 1787-1886. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. 17. ↩︎

- Great Britain. Sovereign (1707-1714 : Anne), Eighteenth Century Collections Online, and Queen of Great Britain Anne. By the Queen, a Proclamation, for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue, and for the Preventing and Punishing Vice, Profaneness, and Immorality. Anne R. Printed by Charles Bill, and the executrix of Thomas Newcomb, deceas’d; printers to the Queens Most Excellent Majesty, 1708. ↩︎

- “George III: well-intentioned but faced with insurmountable problems.” Guildhall Library Blog, 2022. https://guildhalllibrarynewsletter.wordpress.com/2022/04/25/george-iii-well-intentioned-but-faced-with-insurmountable-problems/ ↩︎

- Fitch, Thomas. By the Honourable Thomas Fitch, Esq; Governor of His Majesty’s English colony of Connecticut, in New-England, in America, a proclamation. Whereas his Most Gracious Majesty, from a regard to the honour of God and a concern to promote religion. New London, Connecticut, 1761. PNG. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.00301300/?st=text ↩︎

- Gage, Thomas. Province of Massachusetts-Bay. By the Governor. A Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue… Boston: Margaret Draper, July 23, 1774. ↩︎

- Hewes, Lauren. “The Acquisitions Table: A Proclamation for the Encouragement of Piety and Virtue.” Past is Present. The American Antiquarian Society, 2015. https://pastispresent.org/2015/acquisitions/the-acquisitions-table-a-proclamation-for-the-encouragement-of-piety-and-virtue/ ↩︎

- Burns, Arthur. “The Abdication Speech of King George III.” Georgian Papers Programme, accessed September 5th, 2024. https://georgianpapers.com/2017/01/22/abdication-speech-george-iii/ ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Wolf, Naomi. Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love. London: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2020. 34. ↩︎

- Webb, Beatrice Potter. History of Liquor Licensing in England Principally from 1700 to 1830. London: Longman, Green & Co., 1903. https://archive.org/stream/historyofliquorl020144mbp/historyofliquorl020144mbp_djvu.txt ↩︎

- Linder, Douglas O. “Homosexuality and the Law in England.” Famous Trials. Kansas City: UKMC, Accessed September 6th, 2024. https://famous-trials.com/wilde/329-homosexual ↩︎

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Reformation Necessary to Prevent Our Ruin, 1727,” Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. Updated 29 April 2000, amended 24 July 2002 <http://www.rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1727ruin.htm>. ↩︎

- Rictor Norton (Ed.), “Newspaper Reports, 1728,” Homosexuality in Eighteenth-Century England: A Sourcebook. 10 August 2002, updated 21 July 2018, 2 September 2020 <http://www.rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1728news.htm> ↩︎

- Roberts, Making English Morals, 28. ↩︎

- Binhammer, Katherine. “The Sex Panic of the 1790s.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 6, no. 3 (1996): 409–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4629617. ↩︎

- “Report of the committee of the Society for carrying into effect His Majesty’s proclamation against vice and immorality ,for the year 1799.” Society for Giving Effect to His Majesty’s Proclamation against Vice and Immorality. 1800. 11. https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_report-of-the-committee-_society-for-giving-effec_1800_0/page/n9/mode/2up ↩︎

- Ibid, 13. ↩︎

- 14. ↩︎

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.