Dorothy’s Boy (M.K. Bengtson, 3/10/2009) – Self-Published, Fiction (330 Pages), Free with Kindle Unlimited or $9.99 on Amazon, $12.49 Trade Paperback

Creon:

– Oedipus Rex, Sophocles1

Very well,

I will tell you what I heard from the go.

Apollo commands us – he was quite clear –

“Drive the corruption from the land,

don’t harbor it any longer, past all cure,

don’t nurse it in your soul – root it out!”

Oedipus:

How can we cleanse ourselves – what rites?

What’s the source of the trouble?

Creon:

Banish the man, or pay back blood with blood.

Murder sets the plague-storm on the city.

Oedipus:

Whose murder?

Whose fate does Apollo bring to light?

When we talk about a gender transition – a realignment of the body to suit the soul, such metaphysical endeavors – it has become common parlance to discuss it in term of euphoria. Gender euphoria is the panacea for a lifelong dysphoria, its opposite: a spinny skirt, the first signs of facial hair, an unthinking gender-neutral pronoun. Little things that elevate the transsexual from their gloom. For a trans woman, this often become such a process of purification – the cleansing of her maleness, the removal of all signifiers which once defined her. It is a powerful process, a mystical process. Where did the woman come from? From deep inside, from all around.

Of spirit, of soul.

The picture that I want to propose here of transition is not one of euphoria and dysphoria presented as an oppositional dichotomy, but rather one of catharsis. I mean this in its most original Hellenistic sense. Catharsis was originally the purging or removal of waste from the body, menstrual blood or feces; in our modern verbiage, however, it has become synonymous with the ancient poetic genre of tragedy. Aristotle was the first to make this metaphor, and wrote in his Poetics:

Tragedy, then, is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude; in language embellished with each kind of artistic ornament, the several kinds being found in separate parts of the play; in the form of action, not of narrative; through pity and fear effecting the proper purgation of these emotions. […] For Tragedy is an imitation, not of men, but of an action and of life, and life consists in action, and its end is a mode of action, not a quality. Now character determines men’s qualities, but it is by their actions that they are happy or the reverse. Dramatic action, therefore, is not with a view to the representation of character: character comes in as subsidiary to the actions. Hence the incidents and the plot are the end of a tragedy; and the end is the chief thing of all. […] [T]he most powerful elements of emotional interest in Tragedy- Peripeteia or Reversal of the Situation, and Recognition scenes- are parts of the plot.2

Peripeteia is an ancient literary technique perfectly illustrated by Sophocles’ classic play Oedipus Rex. Oedipus is the king of Thebes, which has become afflicted by a terrible curse that has ruined its crops and darkened its skies. Oedipus was raised outside the city, not knowing his parents, and only came to the throne after the death of his father. Fearing the wrath of the Gods, and suspecting that this curse has arisen due to the mysterious death of the former king, Oedipus declares that his father’s murderer has laid the curse down upon the land, and that he will be the one who finds that person and kills them, driving the curse from the land.

The modern reader will be familiar with the psychoanalytical idea of the Oedipal Complex, the notion that all psychological issues (transsexuality none the least) arise as a consequence of the fundamental infantile desire to kill one’s father and marry one’s mother. Over the course of the play, King Oedipus receives a prophecy from the blind prophet Tiresias that he is his father’s murderer, and that he has also married his mother, the Queen, and now shares her bed. Horrified, Oedipus becomes determined to root out the true murderer, only to slowly realize over the course of the play that Tiresias’ prophecy was true: as a young man, he had unwittingly killed his father, married his mother, and cast down the curse upon his own land. Peripeteia refers to this reversal of fortune, the irony that once Oedipus sought out the murderer, only to discover that murderer within himself. Tragedy arises from this reversal of fortune, and it is the catharsis of this moment – the realization, the emotional devastation, the collapse, the release of unthinkable and inexorable hidden truths upon the world – upon which hinges the entire emotional heft of the play.

In the theory of aesthetics, the two most important aesthetic sensibilities, i.e. the root forces which cause us to find emotion or meaning in art, are beauty and sublimity. In our popular culture, we often parse the aesthetics of a transition in terms of the beautiful. “Trans is Beautiful!” the popular sentiment declares. Every Beyoncé is in on it! While in many ways this is a buzzword, it bleeds out of trans activism and into the ways we conceptualize our lives. Transition is often framed as a move away from a grotesque or distorting Assigned Gender at Birth to a beautiful, happy, good, lovely new gender that has elevated the person from their suffering. The Greek root of dysphoria literally translates to dys-, “bad, difficult,” and -phoria, “to bear.” Euphoria, conversely, bears well upon its subject; eu-, “good, well;” in this picture of dysphoria, euphoria, and transition, the very act of moving to a chosen gender has a moral impetus. It is literally good to be trans.

Aesthetic philosophy has a long and ancient history of linking the good and the beautiful, framing the aesthetics of beauty as an ethics, a moral framework, an analytic that can be distilled down to a rational and objective truth. Plato did so extensively. So did Immanuel Kant, the forefather of modern philosophy. Scientific racism and, conversely, the modern colonial project, emerged in no small part out of a desire to quantify beauty as a metric of human worth (but that’s a topic for another article). By contrast, the philosophy of the sublime is often framed in much murkier terms, and, importantly, does not arise out of this form of moral framework. As a genre, tragedy owes far more to its sublimity than its beauty. In his work The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche writes:

At present, however, science, spurred on by its powerful delusion, is hurrying unstoppably to its limits, where the optimism hidden in the essence of logic will founder and break up. For there is an infinite number of points on the periphery of the circle of science, and while we have no way of foreseeing how the circle could ever be completed, a noble and gifted man inevitably encounters, before the mid-point of his existence, boundary points on the periphery like this, where he stares into that which cannot be illuminated. When, to his horror, he sees how logic curls up around itself at these limits and finally bites its own tail, then a new form of knowledge break through, tragic knowledge, which, simply to be endured, needs art for protection and as medicine.3

The core thesis of these two articles and the lens through which I want to read M.K. Bengtson’s 2009 duology Dorothy’s Boy and Finding Home is that transition is a form of tragic knowledge, and that the trans novel arises out of a desire to balm that tragic incomprehensibility. What I want to emphasize here is Aristotle’s observation that tragedy does not pertain to people or characters, but rather to actions. It is not the trans individual who is a tragic figure, but rather our very fundamental conceptuality of a gender transition as it exists in our modern society which takes upon a tragic structure, our supposition of the action-as-motion from “male to female,” from “female to male.” I want to emphasize in very stark language that it is a severe misreading of the argument I’m making here to claim that I’m saying that trans people are fundamentally tragic or that transition seen through the lens of tragedy is somehow a moral wrong or a sign of its fallaciousness. It is not transition or the trans individual but rather the nature and form of transphobic discrimination itself which provides the grounds for a uniquely trans catharsis.

Nietzsche himself is sharply critical of the notion that tragedy is a spectacle (as transphobes and Post-Modern philosophers often seek to paint the “spectacle” of transness). He writes:

[T]he chorus as such, without a stage, which is to say the primitive form of tragedy, is not compatible with that chorus of ideal spectators. What kind of artistic genre would be one derived from the concept of the spectator, one where the true form of the genre would have to be regarded as the ‘spectator as such’? The spectator without a spectacle is a nonsense. We fear that the explanation for the birth of tragedy can be derived neither from respect for the moral intelligence of the masses, nor from the concept of the spectator without a play, and we regard the problem as too profound for it even to be touched by such shallow ways of thinking about it.4

The key element of tragedy is prophecy, predestination, fate. What makes a tragedy “tragic” is not the fact that there is a poor or miserable outcome, but rather that the outcome has already been written before the main character has even begun to try and change it. A tragic literary structure does not hinge upon a character changing the world, but rather in the character realizing that the world has already been changed, and that the outcomes of their actions have been written from the start. This prophecy often takes on a literal form in the tragedy. This could be through a prophet like Tiresias, or, as is more common in our contemporary literature, through the dreams of the main character, which foretell their doom. Nietzsche observes:

So far we have considered the Apolline and its opposite, the Dionysiac, as artistic powers which erupt from nature itself, without the mediation of any human artist, and in which nature’s artistic drives attain their first, immediate satisfaction: on one hand as the image-world of dream, the perfection of which is not linked to an individual’s intellectual level or artistic formation (Bildung); and on the other hand as intoxicated reality, which has just as little regard for the individual, even seeking to annihilate, redeem, and release him by imparting a mystical sense of oneness. […] This is how we must think of him as he sinks to the ground in Dionysiac drunkness and mystical self-abandon, alone and apart from the enthusiastic choruses, at which point, under the Apolline influence of dream, his own condition, which is to say, his oneness with the innermost ground of the world, reveals itself to him in a symbolic (gleichnishaft) dream-image.5

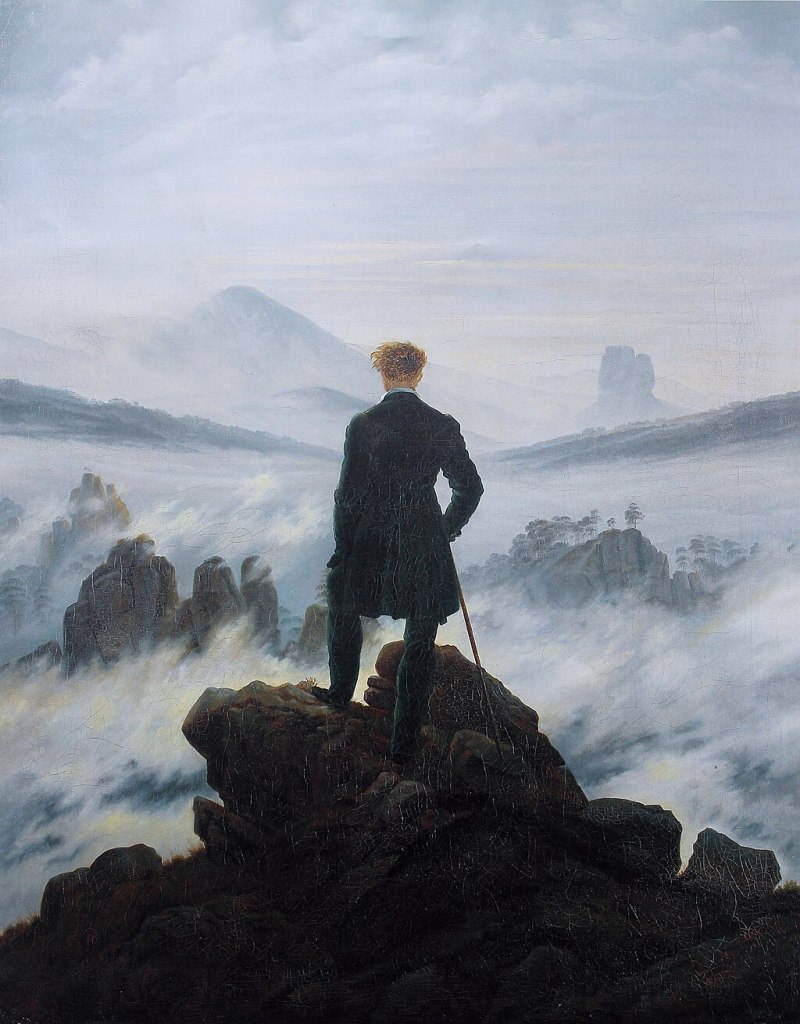

The sublime, as Nietzsche and many other philosophers present it, is the sensation when one becomes overwhelmed by the towering weight of nature, the oneness of God, the totality of the universe, then finds the strength within oneself to rise above it and observe nature as it is. It is a concept that has been heavily associated with the movement of Romanticism, which sought to capture that emotion in its artwork. Sublimity is the emotional response evoked by such awe. Nietzsche is particularly occupied with one’s self-assertion above the abyss or the One. By contrast, however, in the tragic mode, perhaps the most important emotional response to the Sublime is that of surrender, or the acceptance of their doom. This acceptance is the core root of the emotion of catharsis – not a triumph over fate, but a submission to it.

It is perhaps more apt to think of the trans figure in tragedy not as the King, he who has married his mother and killed his father, but rather as the Prophet, the one who foretells the King of his doom. In this sense, the “tragedy” of transition may not even be a tragedy of the transsexual, but rather a tragedy of the transphobe, the one who seeks the destruction of their fate. I do not think that it is a coincidence that the prophet in Oedipus Rex is Tiresias, who famously lived out a significant portion of his life as a woman after Hera cursed her. The transfeminine protagonist is not a tragic figure, but rather a prophet thereof: she foretells doom, her very presence in the story becomes (to the Post-Modern imagination) a herald of the unknown, and the arrival of the sublime, which shall destroy the ego and bring catharsis upon gendered normativities which exist within the world.

Post-Modern philosophy, taking up the aesthetic yoke of yore, often conceptualizes the transsexualized body as a sublime herald of a more general peripeteia of the post-modern self. In this view, the image of the transsexual represents a broader and more fatal destabilization of the human, an argument which trans studies has been all to happy to take up and adapt. Rita Felski writes:

An existing repetoire of fin-de-siècle [end of century] tropes of decadence, apocalypse, and sexual crisis is reappropriated through self-conscious circulation, yet simeltaneously replenished with new meaning, as gender emerges as a privileged symbolic field for the articulation of diverse fashionings of history and time within postmodern thought. Thus the destabilization of the male/female divide is seen to bring with it a waning of temporality, teleology, and grand narrative; the end of sex echoes and affirms the end of history, defined as the pathological legacy and symptom of the trajectory of Western modernity.6

This fundamentally tragic interlinkage of the transsexual, doom and prophecy, dream-images, and the sublime took on its modern form in psychoanalysis, namely the work of Sigmund Freud and his trans interpellation via Magnus Hirschfeld and the field of sexology. One could of course make a rote recitation of Freud’s various ideas about gender non-conformity that have seeped into our culture: auto-eroticism, penis envy, the hermaphroditic bisexual, etc. Instead, I want to highlight how Freud paints the Oedipal Complex as a formulation wherein sexual perversion is a tragic consequence of a psychological failure to develop a correct relationship with one’s body:

It has been justly said that the Oedipus complex is the nuclear complex of the neuroses, and constitutes the essential part of their content. It represents the peak of infantile sexuality, which, though its after-effects, exercises a decisive influence on the sexuality of adults. Every new arrival on this planet is faced by the task of mastering the Oedipus complex; anyone who fails to do so falls a victim to neurosis. with the progress of psycho-analytic studies the importance of the Oedipus complex has become more and more clearly evident; its recognition has become the shibboleth that distinguishes the adherents of psycho-analysis from its opponents.7

The great irony – perhaps tragedy – is that it was the resistance and denial of fate which produced the root tragedy of Oedipus as much as the murder and the incest themself. Perhaps in this sense the true “Oedipal Complex” is not the dogma of psycho-analysis alone, but the spurious belief that an “Oedipal desire” or inversion in general is an active force which one must rail against. This portrait of masters and victims frames sublimity as a force to be conquered, and portrays those who fail to do so as inferior claimants to the “good” of the beautiful sex. When the victim of the sublime who is of course a pervert and a moral degenerate fails to overcome the subliminal drive, they become a manifestation thereof, an aspect of the sublime itself to be mastered and conquered. Perhaps it should not then surprise us that Freud takes up an extremely Kantian argument in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality when he says, “[Inversion] is remarkably widespread among many savage and primitive races, whereas the concept of degeneracy is usually restricted to states of high civilization; and, even amongst the civilized peoples of Europe, climate and race exercise the most powerful influence upon the prevalence of inversion and upon the attitude adopted toward it.”8

It’s important to cite this view of the distinction between a “civilized” degeneracy and a “savage” inversion because it clarifies that, to people like Kant and Freud, the “savage” brain was not physically capable of overcoming its perverse tendencies. What distinguishes the peripatetic inversion of the colonized subject from the degeneracy of the white transsexual is an understanding that the fundamental ability to experience the beautiful can only be obtained by the white race. Thus, what separates the degenerate from the invert is this presupposed ability to resist the Oedipal Complex, to master and dominate it. In this sense, the white rich transsexual becomes a symbol of fate due to their inability to escape the sublime: they represent the failure to colonize, to master the savage and the unknown, a fundamental riveture within the Imperial-Colonial system. This illustrates a fundamental dissonance which can be found in much of the sexological literature, perhaps best embodied by the infamous article “Psychopathia Transsexualis” by David O. Cauldwell:

Among both sexes are individuals who wish to be members of the sex to which they do not probably belong. Their condition usually arises from a poor hereditary background and a highly unfavorable childhood environment. Proportionally there are more individuals in this category among the well-to-do than among the poor. Poverty and its attendant necessities serve, to an extent, as deterrents. […] Although heredity had a part in producing individuals who may have psychopathic tendencies, such pitiful cases as that described herein are products, largely of unfavorable childhood environments and overindulgent parents and other near relatives. […] Progress is being made. Within a quarter of a century social education may serve as a preventive in all but a few cases and social organizations may be able to rehabilitate the few who fall by the wayside.9

We are presented here with two transsexuals – the poor, implicitly racialized inverted transsexual who is already doomed by their circumstances, and the morally degenerate rich transsexual, who really should know better but chooses the “lifestyle” anyway. Even the language of progressive sexologists like Magnus Hirschfeld echoes this language of tragedy, admixture, moral decay, and the sublime. What I find absolutely remarkable about Hirschfeld’s work is how closely he echoes Nietzsche’s language about the nature of tragedy. He writes:

All of these sexual varieties form a complete closed circle in whose periphery the above-mentioned types of intermediaries represent only the especially remarkable points, between which, however, there are no empty points present but rather unbroken connecting lines. The number of actual and imaginable sexual varieties is almost unending; in each person there is a different mixture of manly and womanly substances, and as we cannot find two leaves alike on a tree, then it is highly unlikely that we will find two humans whose manly and womanly characteristics exactly match in kind and number.10

What I want you to take away from this passage is that Hirschfield is not proposing a theory of transvestism that examines the sublimity of the periphery as the productive grounds for understanding gender, but rather reinterpreting the sexual invert within the analytical bounds of the beautiful and the West – in essence, rather than to push beyond that closed circle into the awe of the abyss, to retract the very idea of the transsexual away from the Sublime. “There are no empty points:” Hirschfeld’s sexology was fundamentally incapable of imagining a rupture in that circle. This is a trend that has remained largely unbroken ever since: the transsexual cannot be a discontinuitity with the sphere of the West, or if she is, only insofar as she represents a failure of the conservative comprehension; she is merely an admixture, a species, not the brutalized subject of a tragedy in motion, but the tragedy in and of itself, and thus utterly banal. She becomes an “MtF,” a literalized inversion, identifiable by and inextricable from the social trends which have shaped her, and in doing so attempts to represent herself as a moral representation of a beautiful ideal (or vice). All discourse around the trans body therefore becomes a question of morality – how can the transsexual be beautiful if the transsexual is trans? Dysphoria as a moral perversion. Euphoria as a moral virtue. Sublimity lost beyond the pale.

Dorothy’s Boy (2009)

“I’m not going to be a man when I grow up.”

– Dorothy’s Boy, M.K. Bengtson (2009)11

“You’re nuts, we are boys and boys grow up to be men.”

Kent exclaimed, “Not me!”

“So are you going to grow up to be a woman?”

“I haven’t thought about it like that. I just want to be like my mother.”

Before we deep-dive into these books, two asides. I will be extensively talking about the entire scope of the plot, including all twists, characters, and themes. If you want to read the duology before hearing me talk about it, this is your warning to stop reading and go find the actual book instead. Secondly, I’ll be talking about a lot of heavy topics here, including but not limited to transphobic violence, suicide, murder, rape, death, childhood sexual assault, religious bigotry, dated social norms, and a variety of other things. If you find any of that objectionable, this will also be your moment to click away.

Dorothy’s Boy (2009) is a strange little autofictional childhood bildungsroman about growing up trans in the 50s, 60s, and 70s during the Boomer generation in rural Pennsylvania. When I read the book for the first time, I came away with an impression of a string of vignettes loosely connected by themes of trans identity, religious struggle, and repression in suburban life. That doesn’t do this book justice, though. Bengtson’s vision of childhood is not just a string of recollections but a surprisingly deep psychological examination of transfeminity in the Mid-Century, lingering on vivid images and dreamily bobbing along from one life event to another. While it has many structural similarities to a trans memoir, Dorothy’s Boy excels not in the narrativization of a trans childhood but in those little moments in the interstices which slowly emerge into a vivid panorama of the aging transfeminine mind by the end of the sequel.

Our main character is Kent, later Kelly Anderson, a young ‘boy’ raised within the Evangelical faith by his controlling neurotic mother. In many ways, this parable mirrors the psychoanalytic picture of the transsexual that I outlined above. Though Kent may have had a predisposition to his femininity, it is clear from the very beginning that Kent’s mother Dorothy is framed as a primary reason for his childhood desire to be a girl. In the opening scene of the book, we see Kent dressed up as the Wicked Witch of the West to go trick-or-treating with Dorothy, in what will become a recurring use of Wizard of Oz imagery across the two books. From the beginning, it’s clear that Dorothy’s relationship with her child is infantalizing and often uncomfortably psychosexual. In that opening scene, she holds Kent’s hand across the street (Kent is eleven) and takes off his dress in public in front of Benny Saunderson when he overheats. In a later episode, we see that Dorothy has left a pair of velvet panties in Kent’s underwear drawer, which she then violently scolds him for wearing outside the house with no other clothes on. This pattern of feminine expression being associated with public exposure continues throughout the book, as Kent is repeatedly forced to strip or emasculate himself in public.

The picture we receive of Kent’s psychological development is uncomfortably Freudian. He had a mother so overbearing that people would call him “Dorothy’s boy” and an absent father who was abusive to his mother then left before he was born. Kent develops a severe misandry over the course of his childhood, envisioning men as the root of all violence and developing a terror of being seen as a man. The twist on the classic Oedipal Complex comes, of course, in that rather than wanting to marry his mother, Kent ostensibly wants to be his mother. Kent is the antagonist of her self-centered life; Dorothy only wanted a girl, and dislikes boys as much as Kent does. If one reads Dorothy’s Boy as a Freudian metaphor, then the whole book – and Kent’s entire transition to Kelly – could be read as a psychological portrait of one trans woman’s mental relationship with her mother over several decades. The most compelling evidence for this reading comes at the very end of the book, when Kelly declares her Halloween costume for the year, but even in the process of doing so refutes the Freudian reading of Kelly’s life and transition:

“What costume are you going to wear?”

Kelly thought about it for a moment then replied, “I’ll go as Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz.”

“I am a bit surprised that you would want to go as a character with your mother’s name. Isn’t that the same costume that you wore as a boy in grade school?”

“The costume doesn’t have anything to do with my mother. My grade school costume was the wicked witch. I don’t need to secretly express my gender in a witch’s costume, I’m not Dorothy’s Boy anymore.” Ellen thought she upset her partner. She opened her mouth to speak but Kelly put her fingers over it.

Kelly continued, “I’m going as Dorothy because she finally went home in the movie. It’s so true, there is no place like home, here with you.” She put her hand on Ellen’s arm, Ellen put her head on Kelly’s shoulder. “I love you.” Kelly smiled.12

One of the many reasons this book is exceptional is its sympathetic and nuanced portrait of a trans lesbian in 2009. This penultimate representation of transbian self-actualization is powerful because of its willingness to reclaim the name and mantle of Dorothy from Kelly’s mother. And if the book had simply ended there – had it not had a sequel – that would perhaps be as much meaning as one could draw from it: a psychoanalytical portrait of a transfeminine childhood that, while interesting on its own merits, ultimately owed more to a sexological portrait of the transfeminine mind than anything else and did not strike at the heart of any deeper truth. Dorothy’s Boy, however, has a sequel released later that same year, one which completely opens all of the subtle questions and ideas from the first book; and Finding Home peculiarizes many of the innovations of the first book, and by that token, Dorothy’s Boy demands our deeper analysis.

Recurring motifs become the vehicle for both gender and fate over the course of the book. Early in the book, Kent goes out into the woods with a couple neighborhood boys to kill snakes. The boys call him a sissy and taunt him for being effeminate; Kent’s snake slaughter becomes a way of attempting to prove himself as a man. But when he goes back to the house, Dorothy scolds him for hunting the snakes and doesn’t believe he’s the one who killed them, forcing him to throw the snakeskin away.

Undeterred, Kent goes back out the next morning to keep snake hunting alone. But this time, he discovers a nest with dozens of snakes. With his grandfather’s axe, Kent frantically tries to kill all of the snakes before they bite him, covering his hands in snake blood, then runs away from the scene of the massacre. But though he leaves the dead snakes behind him, the fear and foreboding linger. He narrates:

Instead of feeling relief, he then imagined that some snakes might be chasing him. As he looked back, he thought he felt something in his pants.

He cried, “Oh, dear God, please save me!” He began to stomp his feet to shake out the hidden creature. He stomped harder and harder until his feet stung. No snake came out but that was of little comfort, he was convinced that some creature was in there. Half running, half stomping, he made his way home to the safety of the basement. Immediately, he took off his pants to find the snake only to find a bit of the dry high grass. He laughed, holding the thin golden brown stalk.

He put the axe away then washed the snake blood off his hands. Feeling very tired, he sat in a faded green old metal patio chair. The cold metal sent a shiver though him, a welcome relief after being so overheated. He leaned back, closing his eyes but began to have involuntary shudders. No matter how hard he tried, he could not shake the memory of black striped snakes writing in the thick brown mud. […]

For years, Kent was plagued with nightmares about snakes. He had frequent pangs of guilt for killing them, fearing some sort of retribution for his crime against nature. He had attempted to be like the other boys and it sickened him to do it. For the rest of his childhood, unlike the other boys of Elmwood, he never fished or hunted. He detested killing. Kent had even more reason to feel that being a male was foreign and unnatural, yet he didn’t think he had a choice. Somehow, he would be one someday but he still hated the idea of it.13

This is hardly the only time in the book when Kent attempts to invest himself in a signifier of boyhood, only for it to become an intense recurring motif of his fear thereof. His experience with the snakes comes to be a representation of the phallus in his mind; but as the book progresses and Kent gets older, however, the consequence of the masculine signifier grows increasingly deadly. Early in the book, Kent gets into model airplanes and nearly talks his way onto an airplane flight, only to discover in the next chapter that there has been a horrible aviation accident and a man who was supposed to take him flying has horribly died. He narrates:

Kent didn’t throw up but felt very sick. He went home and tried to nap hugging his stuffed animals to try to forget what happened. He knew that he could have been in the aircraft with Bakot when it went down. He couldn’t forget the image of Bakot lying in the woods without feet. He wondered, how could these men fly airplanes when death was so near? Why was it that men wanted to prove their bravery by death defying actions? He thought back to killing rattlesnakes in the dry river bed, his last attempt to be manly. Once again, he thought that he was not and did not want to be a man.14

A second episode later in the book is even more explicit, this time framing Kent’s attempts to engage in masculine activity not just as a foolish defiance of fate, but as the direct doom of the transfeminine:

A woman cried, “Where is Tommy? Anyone seen ‘im? Go look an fetch ‘im.”

Benny saw a white shape in the water but couldn’t quite make it out. Then he realized what it was, a body floating face down in the water.

Pointing to the body, he yelled, “Kent, look over there! It’s a body, floating in the river!”

The family sprang up and ran into the water. The father reached the spot first and he pulled out a six or seven year old blond haired, large headed boy from the water. He was wearing a pair of short, ragged, cut off jeans. His skin was bluish pale white, limp as a rag, he was clearly dead. The family was weeping and moaning but said nothing intelligible. The father carried the boy’s body and they slowly walked into the forest.

Benny whispered, “Look at that long hair. Is that a boy or a girl Kent?”

Kent thought about it then said, “I don’t really know, I guess since his name is Tommy, he is a boy. Come on let’s get out of here. I think I’m gonna be sick.”

“Yeah, it’s too creepy to go swimming here now.”

Benny and Kent picked up their towels and backpacks and walked back through the woods. The forest was eerily silent as though nature itself was chilled by the event.15

Over the course of this first book, nature begins to emerge as a certain counterbalance to the masculine forces in Kent’s life, and we begin to see the first glimmers of sublimity emerge. Kent associates manhood with death and femininity with the natural world, and over the course of his adolescence, tries to lose himself within the former, convinced that it’s the only way forward with his life. He drives a nice car and goes on dates with girls and slowly, inexorably crumbles under the weight of it all. Masculinity makes him cruel, and the world punishes him for it. In one vignette, Kent bullies the only kid in his grade who’s weirder than he is, Steve Metzger, only to watch him drown on a canoe trip later that week. Immense guilt consumes him, only intensified when Benny brushes it off as “what guys do” and Steve’s mother thanks Kent for always being kind to him. M.K. Bengtson is a master of pathetic fallacy, and the end of this vignette is a particularly deft example of it:

The days following were dark and gray. The bleak weather reflected the sadness pervading Elmwood. Low clouds obscured the sun and a soft drizzling rain soaked the land. Wisps of fog drifted through the trees as though spirits were about. Kent wondered if nature too was mourning Steve’s passing.16

Throughout the book, Kent is convinced that he is doomed to become a man, a worldview informed by his Evangelical upbringing. The clever slight of hand that Bengtson weaves through this book is, even while reaffirming the beliefs of Dorothy and the Church that queerness is a sin punishable by death, slowly building up a relationship between Kent and nature which exists beyond those strictures, weaving the subtle threads of fate throughout his trials and tribulations. It’s here where the power of the Wizard of Oz metaphor begins to reveal itself. For his entire life, Kent has believed that he’s been fated to always be Dorothy’s Boy – the Wicked Witch of the West, fated to be killed by Dorothy herself. Through his entire adolescence, he is trapped within the contradiction of his mother’s indulgence of his femininity and her violent insistances that he not be a ‘queer’ and take ownership of his manhood. This lifelong struggle culminates toward the end of the book with a suicide attempt, where, abruptly, Nature suddenly takes on its own voice:

Gender issues were ruling his life. He could not compete with boys in any way that he felt was good enough. There was always something wrong lurking under the surface in his mind. His outbursts finally cost him the girl that he dearly loved.

He drove around in the cold winter night, wondering if he should drive into a tree or off the road into the river. The idea of ending it all seemed very appealing again. It was a clear moonless winter night, darkness was total except for a dazzling display of the Milky Way stretching across the sky. He longed sleep and not wake up. Death was close, only a simple turn of the wheel would do it. Lots of teens died on these narrow county back roads.

He thought, They will all be sorry, and even line up to see me in the casket, just like Steve Metzger.

His hand started to pull the wheel but he heard something, a quiet calm, female voice.

“Kent, don’t, you have more to do.”

Startled, Kent looked around for who said this but he was alone in the car.

He shouted, “Who said that!” He felt that he was losing his mind. Silence.

Whatever the source, the voice was enough to stop him from killing himself. Slowing down and driving properly, he found a turnaround spot in the road and drove to Dorothy’s house. He quietly opened the door and into his room. The last person he wanted to talk to tonight was his mother. He fell into bed, crying into his pillow making as little sounds as possible.

He wailed, “Why God, do I have to do this? It is so hard. I can’t be like the other boys and now I can’t even… KANT EVEN… keep a girlfriend. I lost Claudia. I’ll do anything you say, please give Claudia back to me!”

He waited for an answer. None came. Instead, he fell into a dreamless sleep.

The next morning, brilliant midmorning sunlight streamed through his window, waking him. The light was cheery and uplifting but Kent hated it. The light reminded him of a world of happiness but he was heartbroken. He got up and stared into the disheveled reflection of himself in the bathroom mirror. The young man in the mirror looked pathetic and ugly to him, even more so than he normally felt about his image.

He talked to his image in the mirror, “You have got to get your act together.” He thought, This can’t end now. Maybe I do have something to do like the voice said.17

This is where the Prophet begins to slowly emerge from the shell of the Boy. Even so, Kent continues to reject the call and cling to a flimsy semblance of tragic masculinity. He has a disastrous experience in grad school, has a disastrous failed marriage where he loses all contact with his two kids, and subsequently gets disowned by Dorothy for being queer. Death is always close at hand – his new nightly routine is to chant “Kent is dead” to himself until he falls asleep. Dorothy’s mental health issues get worse, and the people in his hometown ironically (hardly coincidentally) begin referring to her as the Wicked Witch. This chiasmus of Dorothy and Kent in the Wizard of Oz metaphor is heralded by the slow unfolding of prophecy as Kent comes to accept herself and adopts her new life as Kelly and falls in love with her future second wife, Ellen.

First Kent realizes that in his nightly dreams after his recurring “Kent is Dead” routine, when his male form is shot and killed, Dorothy is always the one who shoots the gun. This leads to a breakthrough in therapy regarding his childhood sexual trauma, and begins to open up the possibility of transition. Then, Kent is plagued by the persistent dream of his mother’s doorstep piled up with mail – and mere days later, he gets a call from the hospital and learns that Dorothy has passed away. The third prophetic dream of herself enjoying sex and orgasming as a woman finally cracks her egg, and from the privacy of her nightly visions, Kelly comes into the world for the first time. This chapter is aptly titled “Awakening,” and begins as follows:

Morning sunlight streamed into the bedroom, bathing everything with glorious color. Floral scented fresh California air flowed over Kent, fast asleep in his bed. A California Jay chattered just outside the window. He was in the midst of a strange and wonderful dream. In it, a beautiful woman was making love to him. He was lying on his back and she was doing oral sex on him. But wait, he thought, something was different. He had breasts with fully erect nipples and most amazing of all, he had a vagina! He was a woman being made love to by another woman! The orgasm he experienced was incredible. Instead of being only in his genitals as he was accustomed to, it flowed through his entire body. Nothing he had ever experienced as a male was anything like this.

He awoke in the midst of a dry orgasm, his body shuddered with ecstasy. Then another wave of pleasure swept over him in a second dry orgasm. As wet ones were deeply disturbing, he found the new ones to be sublimely wonderful.18

Moments later, she is Kelly, and remains so for the rest of the duology.

Nature, feminine pleasure, sublimity, and prophetic dreams of her future body (she gets SRS later) all form this moment of radical acceptance where Kelly finally accepts that she’s not a man. But I want to make a claim here that might be surprising – I don’t think that this is an example of catharsis. In common parlance, yes, absolutely. But this moment is not the reason I’ve written this article, and it’s certainly not the reason why I’ve spent so much time setting up all of these ideas about tragedy and fate. In fact, I would make a further claim that may be even more surprising to my reader – I don’t think that this is necessarily a proper example of peripeteia either! Certainly Kelly has gone from male to female; certainly she has gone from Kent to Kelly. But ultimately there has been no shift in perspective over the course of this book, only of character, and barely so at that. There was never a single point in the book where it wasn’t incredibly obvious that Kent wanted to be a woman. Hell, as a standalone novel, Dorothy’s Boy can’t even be called a tragedy. If anything it’s a comedy, albeit one that is neither funny nor light-hearted – Kelly figures her shit out, leaves Pennsylvania for San Francisco, gets all the toxic people out of her life, and even gets to have the 2009 lesbian version of marriage at the end. It’s hardly a comedic book, but in the Greek sense of the word, it fits the bill.

No, if there’s any tragedy in Dorothy’s Boy, it is a tragedy of manhood, specifically white queerness and white queer manhood in Mid-Century suburbia, one which Kelly prophesied from the very beginning of the book and which reaped its gruesome conclusions in death from the start to the end. The tragic figure was never her, but rather her childhood friend Benny, who was her foil and has been mentioned a couple times here already. Benny was also queer, and probably in love with Kelly the whole time, but he had the enormous misfortune to be the son of a Evangelist, who Bengtson gives us an unpleasant description of early in the book:

Bill was busy writing his latest sermon on the depravity of the homosexual lifestyle. It was a recurrent theme in his ministry. He was in fact, famous for his flamboyant histrionics in the pulpit of his tiny church on the edge of town. People would go to listen to his sermons partly because of the entertainment value. Reverend Bill however was deadly serious. He didn’t care why they came as long as they kept coming and listened to his message. […]

Reverend Bill preached sermon after sermon about cleaning up society from all sorts of depravity, perversion and gluttony. Sexual sins were a favorite topic and drew the biggest attendance. He was very charismatic but few took him seriously. Still, they dutifully filled his offering plate each Sunday. To them, it was the ‘Reverend Bill Show.’ The irony was that many of the parishoners were in illicit homosexual relationships, ones unknown to their spouses.19

Unlike Kent, who was never quite able to stomach being a man, Benny took aggressively to his manhood, constantly pressuring Kent into being more manly and throwing away his femininity. But he was fleeing queerness no less than Kent was. Fits of homosexuality would often be followed up with slurs and anger, and Benny had even less leeway for survival in his household than Kent did. Their friendship breaks down in high school as things quickly begin to spiral downward for Benny. His father gets more controlling as his rebellious streak grows, sending him to what essentially seems like the Pennsylvania boarding school version of conversion therapy. When Benny comes back from the boarding school more rebellious than before, he accidentally stumbles upon his father having an affair and flees the scene, only for his father to call the cops and order them to arrest Benny for ‘stealing’ his car. Faced with the very real possibility of incarceration, Benny flees to the draft office, where he signs up for the Navy and leaves for Vietnam just as the police arrive. He escapes prison in the military, and his father keels over from a heart attack a few weeks later. Bengtson writes:

Benny left for boot camp, not bothering to see his family. In a few weeks, Benny was on a supply ship in the steaming waters off the coast of Vietnam. He would spend the next two years in that hellish environment. He did not get along with anyone in the service, was nearly given a court martial, and by the time he got out, he was a severely disturbed man.

Bill was a changed man after the incident, he stopped having affairs and attempted to put things right with Betty. He repeatedly wrote to Benny in the Navy but Benny threw away the letters unopened. Bill’s health deteriorated as he suffered from a series of heart attacks, looking twenty years older […] One Sunday, in the midst of an unusually vitriolic rant, he clutched his right arm, his eyes bulged from his reddened face and he collapsed at the altar.20

What interests me here about the letters detail is how closely it mirrors Kelly’s vision of the unopened mail on Dorothy’s porch right before Dorothy dies. But whereas Kelly prophesizes the letters as an omen of death, Benny pays them no mind whatsoever. Certainly there is a reading to be made here about the parallels of homophobic parents dying alone and unloved by their queer children – but I think there’s a more interesting reading that Kelly’s vision of the unopened letters is not just a herald of her mother’s death, but the death of Benny too.

The second to last scene of the book is the final confrontation between Kelly and Benny, neither of whom have seen the other in years. After a briefly cordial exchange, it becomes very obvious that Benny did not come out of Vietnam and the loss of his father with a rosy picture of queer identity:

He mumbled, “Ah, Kent, I don’t know… ah… what fork to use.”

“It is Kelly, Benny. Can’t you see that I am not Kent in any way, shape, or form?” She gestured with her hands toward her body, “Benny, to answer your question, you put the napkin on your lap and take the small outermost fork first.”

Irritated, Benny pecked at the shrimp, finally picking them up with his hands. With a mouth full of shrimp, he said, “Remember when we used to go to Luigi’s for Hoagie submarine sandwiches, Kent?”

“Yes, I do Benny but please call me by my name. It is Kelly.”

“I don’t see anyone named Kelly, only my old buddy Kent. I know you think you are a woman Kent, but I am here to tell you that you are not and can never be. I had a message from God to contact you. I called around Elmwood asking about you and our old school chum, Shaun Simpkins, told me you lived out in California. He told me that you were doing this sex change thing. I knew right then and there that God was sending me to minister to you.”

“Is this the mission that you were talking about? You sound like your father, Benny. You thought his beliefs were homophobic crap even in the sixties, what happened?”

“I realized, years after he died, that my father was right, all along. He was a saint in a sinful town. He was the lone voice of God in a modern day Sodom and Gomorrah. He died without me ever saying I was sorry about stealing his car and running off to the Navy. I hurt him bad. One night as I lied in bed, he came to me in a vision. I suddenly saw everything his way and how right he was. I decided that night to preach the gospel and take up my father’s burden to drive out gays and lesbians where ever I go.”

Kelly said, nervously, “So how do I exactly figure into this mission of yours.”

“It is immoral and sinful to change your sex. God doesn’t make mistakes. You were my best friend when we were kids and I owe it to you to keep you from this abomination. I don’t want you to go to hell.”21

What I find interesting about this is that, lining the timelines up, Benny would have started receiving “visions from God” at around the same time as Kelly – God, of course, being a mental stand-in for the voice of his father. Of all the ways that Benny foils Kelly in this book, I find this to be the most compelling. Not only does it illuminate the stark difference between their life trajectories as queer people, but it also illustrates how, from the very beginning of the book, Kelly has framed her transition through moral terms and terms of the beautiful, even as subtle forces of the sublime have moved through her life. This scene fascinates me because it seems that in some important way, the motivation behind Benny’s claim that it is “immoral” to be transgender arises from the exact same source and upbringing as Kelly’s repeated assertion that it would also be immoral to be a man. It’s the same rhetoric, the same logic spun around. Both Benny and Kelly were raised in the same faith, taught the same lessons about right and wrong and the world they were meant to live in. Both of them grew up queer in a homophobic small town, both of them began having prophetic dreams after a lifetime of abuse and trauma. The only difference – the most important difference – was that Kelly managed to carve out room for herself to be queer in the world, and Benny did not.

Benny lusts after Kelly. When he sees her in a swimsuit, he tries to kiss her despite his deep loathing. When Kelly pushes him away, Benny has a brief crisis of faith, then grows violent and physically assaults her. He knocks her unconscious into the pool, where she nearly drowns, then flees to meet his fate:

Benny looked at Kelly’s blond hair, spreading out in the water. The image of the dead boy floating in the river at Pickering years ago, flashed into his mind. He couldn’t summon the courage to approach Kelly. He suddenly realizes what happened.

“Oh what have I done?” he cried, “WHAT HAVE I DONE? OH DAD, WHAT HAVE I DONE?”

Panic overcame him, he ran in circles around the patio, not aware of what he was doing. In a few seconds, he partially came to his senses and saw the gate to the street, bolted down the path, stumbling halfway. His hands were shaking, he fumbled for his car keys, nearly dropping them. He leapt into the car, slamming the key into the ignition and floored the throttle. The ancient engine roared to life. The old car seemed to howl in protest as he dropped it into first gear and popped the clutch, lurching away at top speed. He was running away, running to escape from Kelly’s body floating in the water, running to escape from his desires for another man and most of all running to escape from himself.

His father’s face appeared in the windshield silently mouthing something. Benny closed his eyes, weeping, choking for air.

“Dad, I’m so sorry, I didn’t mean to hurt you, I only wanted you to love me. I tried to make it up to you. I messed it all up. Oh God, I killed Kent! I loved him!”

The road took a turn, the car careened off the pavement and into a neighborhood park. A row of small bushes did little to slow the vehicle. A sickening bang and the sound of breaking glass shattered the evening silence as the car collapsed around the trunk of a large palm tree.

[…] Losing consciousness, he heard the radio playing, “I can’t get no..ah sa..tis..fac..tion…” He half smiled, his blank eyes stared into nothingness.22

The parallels between this death scene and Kelly’s suicide attempt in the car should be obvious. What differs is that when Kelly was able to hear the voice of fate telling her not to end her life, Benny had completely blocked it out. For Kelly, even when the “darkness was total,” the Milky Way still lit her path; but Benny cannot help but collide with the void, and disintegrate upon contact with it. In effect, what we get here in this scene is a dark mirror of what might have happened to Kelly had she not been able to grapple with her transfemininity. This moment, far more so than with Kelly, could be considered catharsis. At the last possible minute, Benny realizes his truth, and the subsequent collision provides the immediate emotional impact. But even though this is a cathartic moment, it is not a peripatetic one. Benny might have reached an acceptance about his queerness, but his worldview has not shifted. Nothing that happened over the course of this book to either of these characters was inevitable or truly determined – even in these final moments, Kelly and Benny are both making active choices in the way they approach each other, and it is those choices (and the moral ideals behind them) which drive this final confrontation, not any matter of doom, destiny, prophecy, or fate. The characters change their world; the world does not change the characters. Thus, Dorothy’s Boy taken as a standalone novel without consideration to the sequel cannot be considered a tragedy,

At this point, I want to revisit our Freudian analysis from earlier in the article. Taken in isolation, Kelly’s choice to dress up as Dorothy to reclaim her story seems like it could be a subversion of the Oedipal Complex trope. But knowing that Kelly and Benny represent two quasi-symbiotic views about the moral values and aesthetics of queerness, I want to interrogate this ending from the perspective of them embodying together a Freudian picture of sexuality. Benny is wracked with the guilt of having killed his father; Kelly has taken on the guise of femininity she always wanted, but moreover has replaced her mother as Dorothy, even as Dorothy has become the embodiment of the Wicked Witch. Benny has replaced his father too – first in life, then in death. While both Kelly and Benny have experienced tragedy on the personal level, neither of them have experienced what I would describe as a queer peripeteia, an experience that has fundamentally challenged either of their core narratives of becoming or senses of self. Neither of them have been proven incorrect in their perceptions of the world beyond a surface level (yes, the difference between “I am a sinful fag and that’s fine” and “I am a sinful fag and deserve to go to hell for it” is surface level); no radical life-altering truths have changed their view of their own failures; they have not broken the circle, so to speak – or if Benny did, then it was only briefly, obliquely, and he did not survive the contact.

If anything, I would argue that Dorothy’s Boy is most powerfully understood as an examination of the psychological failure to achieve queer peripeteia. At various points in the third act of the book, both Kelly and Benny had glancing contact with the forces of fate and sublimity, yet both of them refused the call, refused to let the world act upon them. Yes, Kelly might have survived, transitioned, gotten the girl. Love did win, or something. But neither were able to escape the moralizing of their childhood; and in the course of two opposing viewpoints within the same moral conceptuality coming head to head, the reader leaves Dorothy’s Boy not with the impression of the titanic catharsis of its characters, but rather the moral parable of queer acceptance and a coming to self. It provides the satisfaction of a well-written fable, not awe. Case and point: aside from the bit about Kelly dressing up as Dorothy and some aftermath of Kelly learning about the car crash, the epilogue is basically just a feel-good sex scene with Kelly and Ellen having fun and gender euphoria.

Remember, tragedy is defined not by characters but by actions, grand forces, and their various transmutations. At its heart, Dorothy’s Boy is a transition narrative – a complicated one, one which defies easy analysis, but a transition narrative nonetheless. The plot of the book does not involve a peripeteia of that core fundamental conceit. It’s a character piece: the characters change, feminize, but their understanding of transition and queerness remains unmolested.

Next week, I’m going to tell you about the sequel to this book, Finding Home, and why I’ve spent so much time laying out this picture of tragedy. Before I leave you, though, I want to linger on one thing that may jump out in view of the title of the second book. Let’s return to the passage where Kelly is declaring that she’ll dress up as Dorothy now:

Kelly continued, “I’m going as Dorothy because she finally went home in the movie. It’s so true, there is no place like home, here with you.” She put her hand on Ellen’s arm, Ellen put her head on Kelly’s shoulder. “I love you.” Kelly smiled.23

To put it simply, this is an absolutely diabolical piece of setup on M.K. Bengtson’s part. In fact, basically every single thing that happens in Dorothy’s Boy is setup for the stakes of Finding Home. But you’ll have to tune back in next week if you want to find out why 😉

- Sophocles. The Three Theban Plays: Antigone, Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin Classics, 1982. 164. ↩︎

- Aristotle. Poetics, trans. S. H. Butcher. Cambridge: Internet Classics Archive. VI. https://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.1.1.html ↩︎

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Ronald Speirs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. 75. ↩︎

- Ibid, 38. ↩︎

- Ibid, 19. ↩︎

- Felski, Rita. “Fin du siècle, fin du sexe: Transsexuality, Post-Modernism, and the Death of History.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 566. ↩︎

- Freud, Sigmund. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, trans. James Strachey. New York: Basic Books, 2000. 92. ↩︎

- Ibid, 5. ↩︎

- Cauldwell, David O. “Psychopathia Transsexualis.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 40-41, 44. ↩︎

- Hirschfeld, Magnus. “The Transvestites.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 37. ↩︎

- Bengtson, M.K. Dorothy’s Boy. Self-published, 2009. 32. ↩︎

- Ibid, 319-320. ↩︎

- 25-26. ↩︎

- 91. ↩︎

- 150. ↩︎

- 122. ↩︎

- 234-236. ↩︎

- 288-289. Some of these page numbers might be off btw, Kindle is weird on my phone ↩︎

- 106-107. ↩︎

- 228-229. ↩︎

- 312-314. ↩︎

- 318-319. ↩︎

- See 12. ↩︎

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.