This is the second essay in our A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature series. You can find the first essay “The Moral Origins of Obscenity” here, or a complete series listing at the end of the essay.

Sixty Years of War

Now, if you were educated in North America, it’s very likely that you learned in school that the “French and Indian War/Seven Years War,” the “American Revolution,” and the “War of 1812” were three distinct and separable conflicts from each other. While this may hold broadly true from an Americanist standpoint, it is not an accurate picture of global geopolitics at the time. According my records, about 77% of the views for this website currently come from Americans and Canadians, so I hope that my European readers will pardon me for taking the time to properly contextualize this early period of American history. Understanding why British and American social history diverge during the early 19th century is absolutely crucial to understanding the modern state of trans publishing, because many early laws criminalizing obscenity, cross-dressing, and licentious publications arose as an often-incidental side effect of the schism.

In the broadest terms, the Sixty Years War was a series of interlocked conflicts between the British and the French over control over North America. The French had a vested interest in American independence as it challenged the British supremacy over the Atlantic Ocean and the New World, whereas the British, who still controlled Canada and a large chunk of the Pacific Northwest after the revolution, were struggling to maintain their hold on the American colonies even as they strengthened their naval dominance over the Atlantic. Britain and France were not the only belligerents in the Sixty Years War. While post-colonial propaganda might not consider them “nation-states,” there were a number of pre-existing countries in the Americas that also fought in this war, most notably the nation of Haudenosaunee, colloquially known as the Five Nations or the Iroquois Confederacy by colonial powers, which spanned the vast majority of the modern Rust Belt and straddled the colonial boundaries between the two Empires. I want to include a graphic that shows the extent of Haudenosaunee because it is an important tool to dispelling the organizing mythos of the British vs. French mentality in the American Northeast at the time.

Even this map doesn’t truly capture how large Haudenosaunee was. By my conservative estimate, this expanse would have covered somewhere in the ballpark of 250,000 sq. miles of land, which would make it roughly the 41st largest country in the world, about the same size as Afghanistan. From a population standpoint, there are wildly varying scholarly accounts of how many people lived in Haudenosaunee during this time. All accounts agree, however, that there was a precipitous drop in the population during the 17th Century due to epidemics and genocide. What also should be noted is that the Nation of Haudenosaunee is not only extant, but actually has more people today than they did in 1700. Today, the tribe numbers a population of over 200,000 people, and they even field their own national lacrosse team (a sport they invented) in international competition.

The Sixty Year War in the Americas is perhaps best understood not as a colonial struggle between the British and French (and later the United States) over the New World, but through the lens of Haudenosaunee’s desperate struggle to survive while surrounded by hostile foreign powers on three fronts. The Haudenosaunee would ally with whichever power was most politically expedient in the moment, attempting to play them against each other and preserve their land and fortunes. It is a bleak reminder of their situation and the genocide which enabled it that no matter who they allied with, the Iroquois were always the ones who lost in the Sixty Years War.

But even all of this context is often overshadowed in the European imagination by the conflicts between the British and the French on the European mainland during the latter half of the Sixty Years War, after the American Revolution had concluded and both Britain and France had lost substantial influence over the American colonies. In 1792, the French Revolution would erupt not just in France but across the entire Continent, accompanied as it was by a wave of foreign conquest by the new French government. These bloody images of the overthrowing of a monarchy, accompanied by the stark violence of the Reign of Terror and the rise of the Jacobins as a political force in the British imagination, was a direct influence upon the Treason Act and Seditious Writings Act of 1795 that we mentioned briefly in Part One, and it would become one of the primary national fears which drove the British Reform movement in the first half of the 19th Century. In direct response to the Revolution, the British would spearhead the first of six Coalitions designed to counter the French, which would result in a period of near-uninterrupted warfare on the Continent from 1792 to 1815. That same period would witness the birth of modern democracy in Europe, and, of course, the rise of our least favorite bloody-thirsty short king, one Napoleon Bonaparte.

Early American history elucidates the inciting force for both the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. The second president of the United States, John Adams, was disposed toward the British and their interests; but the third president, Thomas Jefferson, had previously been the United States Minister to France, and was inclined to turn American interests away from the British and toward the French. It is also necessary to understand that one of the primary causes of the American Revolution was a conflict between the colonists’ desire to expand Westward and the British government’s desire to honor a series of peace treaties made with the various Native nations, especially the Iroquois, at the time. In the Declaration of Independence, written by Jefferson, it states:

[King George III] has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. […] He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.23

Thomas Jefferson was one of the most prominent architects of Manifest Destiny and the genocide of the Native Americans. After being elected president in 1800, he would go on to negotiate one of the most consequential deals in global history, the Louisiana Purchase. The French had recognized that their influence in the Americas was waning, and selling the entire Midwest to the United States would be a far more effective strategy to counter British supremacy in the Atlantic than attempting to wage a trans-Atlantic war they could not conceivably win. One of the stipulations of the 1783 Treaty of Versailles that ended the American Revolution was a provision that the border of the United States would end at the Mississippi River, essentially capping the ability of the newfound nation to expand West even as British North American (Canada) and the French territories continued their Western march. Not only did the Louisiana Purchase double the size of the United States, it also completely freed the colonists to expand as far West as they please, neutering one of the few British victories in the Treaty of Versailles. If Haudenosaunee was large, then the Lousiana Purchase was massive:

Overnight, the Western half of British North America went from an isolated territory bordered only by a few scarce French garrisons to a thousand mile border with a hostile Empire directly to the south. When before the British could have essentially cut off aid to French troops by blockading New Orleans, it now had an adversary who not only had homeland advantage, but also had a loud and vested interest in expanding their land West – and also possibly North. Fearing a renewed French invasion of the New World with overwhelming American support, the British proceeded to invade France itself.

This campaign against the French went on for two years between 1803 and 1805, and it ended with two of the most decisive military defeats in history: an absolute naval victory by the British at the Battle of Trafalgar in October of 1805, and an absolute land victory by the French over a primarily Austrian and Russian force at the Battle of Austerlitz in December of 1805. With Napoleon’s navy essentially obliterated, Britain had wrestled control over the Atlantic Ocean even as their failure to aide Austria or Russia paved the way for Napoleon to steam-roller his way across the entirety of Eastern Europe in the years to come. Rather than rebuild the navy, though, Napoleon pioneered what would become known as the Continental System, an economic blockage that united nearly the entirety of Europe in an embargo against the British. The Continental System went into effect in 1806, and in 1807 the British would respond with a counter-blockade against the French, one that accompanied a significant increase in the policing of the Atlantic Ocean. Under their trade embargoes, both the British and the French stipulated that a cargo ship following the regulations of the other other power could be detained and its cargo seized. In principle, this seizure would affect economic goods most strongly, but in practice it was the seizure of humans that would eventually lead to the War of 1812.

The British began heavily policing American activities in the Atlantic Ocean and impressing American sailors into service on British naval vessels, and tensions in both the Atlantic and the Mid-West eventually escalated to the War of 1812. By pitting the Iroquois in Tecumseh’s Confederation on the British side and the Creeks and Cherokees on the American side against each other, the combined Imperial violence succeeded at finally decimating all major remaining Native American military powers east of the Mississippi River and north of Georgia, putting a permanent end to Haudenosaunee as a major political power in the region. Moreover, the British attempted to weaponize American slaves against their owners, enlisting Blacks with the promise of freedom after they won the war. That victory, of course, never came, and in many ways the War of 1812 calcified the slaveholding interest within the American government. In considering the legacy of the War of 1812, scholar Jason M. Opal writes:

[T]he War of 1812 was a victory for all the major white interest groups in the southeast region of the United States, many of which had previously been at odds. In particular, speculators – who tended to be political and military leaders – and poor settlers – who were often seeking to escape governments run by such men – “won” enough land not to have to worry about who got what. In western North Carolina, for example, poorer settlers had long struggled to gain title to lands they had originally purchased in 1783 and 1784 but that had been transferred to state and federal authority and retroceded, in part, to the Cherokee. This caused considerable tension between and among settlers, borderland elites, and the federal government. The devastation of Cherokee and Creek lands that culminated during the War of 1812 not only opened up huge tracts of land for all kinds of white migrants but also convinced large numbers of them that their government, or at least parts of it, shared their fundamental interest in landed independence. Whether or not those migrants had slaves, and even whether they claimed one hundred or one thousand acres, mattered less than it had a generation previously. That is, the sheer availability of land and the shared narrative of wartime suffering muted the many conflicts of interest between emigrant streams. Combined with the U.S. defeat of the Mississippi Territory Creek Indians in the Creek War of 1813-1814, the War of 1812 made the rapid expansion of slavery not only possible but also blameless; the race-nation, rather than any one territory or polity, had won the right to make of the Gulf Coast what it wished. The victors also did not have to tolerate any possible thread to slavery, which is why, in many respects, the Seminole War of 1818 followed quite naturally from the aftermath of the war in 1815. Put another way, we should consider the War of 1812 as a turning point in the history of slavery in its broadest sense, and we should link the long-term results of the conflict to the rise of the militant slave owners of the antebellum period.5

Meanwhile on the British side of things, their loss at the Battle of New Orleans, and indeed the entire war, was heavily overshadowed by the ongoing drama of the Napoleonic Wars, which involved far more troops and a far more significant power struggle. With a triumph at the Battle of Waterloo, the British had their own national victory over France’s Continental System to celebrate. However, the war with the Americans still had its impacts:

The truth is, the British were never happy. In fact, their feelings ranged from disbelief and betrayal at the beginning of the war to outright fury and resentment at the end. They regarded the U.S. protests against Royal Navy impressment of American seamen as exaggerated whining at best, and a transparent pretext for an attempt on Canada at worst. It was widely known that Thomas Jefferson coveted all of North America for the United States. When the war started, he wrote to a friend: “The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us experience for the attack of Halifax the next, and the final expulsion of England from the American continent.” Moreover, British critics interpreted Washington’s willingness to go to war as proof that America only paid lip service to the ideals of freedom, civil rights and constitutional government. In short, the British dismissed the United States as a haven for blackguards and hypocrites.6

What does any of this have to do with transliterary history? More than you might think. With their victory at the Battle of New Orleans, the United States had received essentially a free mandate to expand West as much as they wanted to. This was only compounded by the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, which declared that “the political system of the allied powers is essentially different in this respect from that of America”7 and that the US would tolerate no European colonialism within its borders.

I have highlighted Haudenosaunee here because the region is the birthplace of the American cross-dressing ban. I won’t linger here, because Part Four of this series will cover the issue in extensive detail, but from 1843 to 1851, cities in Missouri, Ohio, Illinois, Tennessee, and New York would pass the first explicit bans on cross-dressing in the United States. While only New York’s ban would explicitly cite a fear of disguise as the indigenous Other as its inciting cause, understanding the fall of the Iroquois Confederacy in the view of US-UK relations brings to light a crucial way in which this part of the United States emerged in the national consciousness as a contested transverse, the imagined location of British tyranny, and the gateway to the American West.

In a very real sense, the entire project of the Sixty Years War was the conquest of Haudenosaunee, built off of the voracious desire of the American colonial to settle the Ohio River Valley and its surrounds. Over the coming decades, Indian Removal would see the Iroquois largely displaced and the white colonists to overwhelmingly take their place. Importantly, the white colonization of Haudenosaunee and its full incorporation into the American project was not the death of this intense fervor over the land, but rather the incipient site of its transmutation. The Midwest would continue to be a place of transit for the rest of the 19th Century for slaves, free Blacks, Mormons, Catholics, and Central and Eastern European immigrants, and thus the American objective would shift from offense against the Natives to a defense of its new “heartland” against the foreign invader (still Native-coded in the White imagination, both vis a vis the “native” white settler and the “invading” immigrant). For the slaveholding parts of this region, namely Missouri, this would also be conceptualized as the defense of the slave-owner’s right, and this blueprint would play an extremely consequential role on the general development of transgender law during this period of American history. We will return here in Part Three and Part Four of this series, but before we can get there, we need to wrap up our discussion about the history of British obscenity law and the outcomes of William Wilberforce’s moral crusades.

British Abolitionism and the Slave Trade Act of 1807

Another war swept up in this broad Great Power struggle between the British and the French was the Haitian Revolution, which lasted from 1791 to 1804 and resulted in the establishment of the free state of Haiti. Looking at the context of the Haitian Revolution, a slave revolution that became a war of independence, lays bare the hypocrisy of both the French and the British on the slavery issue. More importantly, looking at Wilberforce’s career through the Haitian lens dismantles even the nuanced picture of his presupposed benevolence that I presented to you in the first essay in this series. Fergus writes:

There is a close link between rightwing, neo-imperialists’ attitude to Wilberforce today and abolitionists’ reactions to the Somerset case [a 1772 landmark ruling that made it illegal to transport a slave out of Britain]. To many scholars and laypersons the story of the abolition of Britain’s slave-trade and African emancipation is synonymous with the biography of William Wilberforce. The veneration of Wilberforce and the restoration of his sainthood status are less

acts of hero-worshipping than a case of Britain’s moral leadership of North Atlantic imperialism, deliberately blurring the historical fact of Britain as the Dominant slave-trading nation throughout the eighteenth century. Yet, in many respects, his iconic profile mirrors that of Sharp particularly in downplaying the defense of slavery against the glorification of abolition of the Slave trade. The logic of Wilberforce as the primary icon of British imperial conscience is falsely premised on the subliminally fashioned portrait of him as emancipator of enslaved Africans. This portrait sells best when held up against the historiography that emphasizes Africans as collaborators in the crime of ‘selling their brethren into slavery.’ The same image makers craftily marginalise African freedom fighters or erase them from the noble struggle for freedom against vested interests in the trade and the institution of colonial slavery. It is not passing strange that celebrants of moral imperium persist in a-historically twinning of Wilberforce’s achievements in abolition of the trade to emancipation, and often confusing the two issues. By the time of his retirement from parliamentary politics in 1822, Wilberforce had done nothing that could link him to a call for immediate and unconditional emancipation. The window dressing is important to cultists of imperial benevolence; for one thing, it explains the twenty million pounds sterling that the British government advanced in 2006-07 to a select group of cultural and intellectual image-makers to ensure the maximum impact of ‘Wilberfarce’, as Tony Martin sarcastically rebranded England’s bicentennial celebrations. To Martin, ‘Amazing Grace’ and other films such as ‘Amistad’ are loaded with “subtle innuendos” and “contentious issues” of epistemology and pedagogy; cinematography in this case is seen as is a cultural imperialist tool that packs images of disempowerment overtly and subliminally.8

In his landmark book The Black Jacobins, C.L.R. James examines how Wilberforce’s choice to take up the cause of the slave trade in the first place was not a strike of divine inspiration, as the Evangelicals frame it, but rather a move of political expediency:

But the West Indian vested interests were strong, statesmen do not act merely on speculation, and these possibilities by themselves would not have accounted for any sudden change in British policy. It was the miraculous growth of San Domingo that was decisive. Pitt found that some 50 percent of the slaves imported into the British islands were sold to the French colonies. It was the British slave-trade, therefore, which was increasing French colonial produce and putting the European market into French hands. Britain was cutting its own throat. And even the profits from this export were not likely to last. Already a few years before the slave merchants had failed for £ 700,000 in a year. The French, seeking to provide their own slaves, were encroaching in Africa and increasing their share of the trade every year. Why should they continue to buy from Britain? Holland and Spain were doing the same. By 1786 Pitt, a disciple of Adam Smith, had seen the light clearly. He asked Wilberforce to undertake the campaign. Wilberforce represented the important division of Yorkshire, he had a great reputation, all the humanity, justice, stain on national character, etc., etc., would sound well coming from him.9

It is not accurate to claim that the slave trade was abolished out of any sort of moral prerogative from any of the imperial powers involved. Rather, it was a matter of political and economic expediency, little more than another pawn in the great tug of war between two intercontinental empires. Case in point: Saint-Domingue was one of France’s most profitable growing colonies at the point where it rose up on August 21st, 1791. They don’t usually teach about the Haitian Revolution in the United States (wonder why), so I think it’s important to emphasize that over 100,000 slaves joined the revolt, and by 1792, they had occupied a third of the island. Fearing a complete loss of the colony and swept up in a revolutionary fervor of its own, France partially abolished slavery in the region in 1792. Almost immediately after, France would declare war on Britain – and knowing of the discontent of the white colonial planter class in Haiti, Britain smelled blood in the water and took advantage of the turmoil to try and break the French dominion by reestablishing slavery in the region.

Britain successfully invaded Haiti in 1793, and captured the capital of Port-du-Prince in the Battle of Port-Républicain in 1794. In another world, this might have been the end of the revolution, but later that same year the Haitians managed to expel the Spanish from the other half of the island and run the British from the Tiburon Peninsula. Humiliated and angered, the British sought a total conquest of the islands and sent thousands of men to the West Indies (upon the mandate of William Pitt, the same man who had urged Wilberforce to forward the abolition of the slave trade just years earlier), only to be rebuffed by yellow fever and resistance from the islanders. By 1798, the British had ordered a complete withdrawal from the island, leaving it once again in the hands of the freed slaves and their leader, Toussaint Louverture.

With the British gone, four years later it would be the French who were invading once again, this time under Napoleon’s instructions to reinstate slavery in the region and throughout the Empire. Napoleon would successfully took back control over the region, but when it became clear to all that the French intended to reinstate slavery, the Haitians began to rebel again in 1802. This was the other context in North America besides the Louisiana Purchase that contributed to the 1803 British invasion of France – not just the French enabling of American slaveholding interests, but the restitution of French slavery in the West Indies as well. Less than a decade after the British had been invading Haiti to protect the slaveholding interest, they were now attacking the French for trying to restore slavery. With the French properly distracted by their war with the British, Haiti would be able to finally declare its independence in 1804, and leaving an indelible impact upon the abolitionist movements in both Britain and the United States alike.

We return now to the history mentioned in the first section of this article. The Battle of Trafalgar had taken place in 1805, and by 1806, the trade war between the British and Napoleon’s Continental System had begun in earnest. With the French looking to reestablish themselves in the slave trade and the British looking for ways to curtail French maritime power, the regulation and policing of the slave trade became a political possibility for the first time as an expression of anti-French sentiments.

At the same time, and as far as I can tell, completely unrelatedly, one of the provisions that had been written into the Constitution of the United States was soon approaching its date of activation. One of the many compromises on slavery was a set date after which the abolition of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade (not domestic slavery) would be permissible. In the Constitution of the United States of America, the Founders wrote that “The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a tax or duty may be imposed on such importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each person.”11 By 1806, the writing on the wall was clear that this policy would ultimately be implemented, as ought to be evinced by the massive spike in slave importations in the four years leading up to the ban. In his December 1806 address to Congress, Thomas Jefferson (a proud slave-owner himself) said to Congress:

I congratulate you, fellow-citizens, on the approach of the period at which you may interpose your authority constitutionally, to withdraw the citizens of the United States from all further participation in those violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, and which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country, have long been eager to proscribe.12

The moral dissonance of owning over 600 slaves but worrying about the “violations of human rights” on slave ships is wild. But I digress. In 1807, both Britain and the United States would pass laws which abolished the importation and international trafficking of African chattel slaves. Britain would go one step further and also abolition the practice of domestic slavery (though this was mostly nominal, as a system of “apprenticeship” would take its place and serve a similar role for the next thirty years).

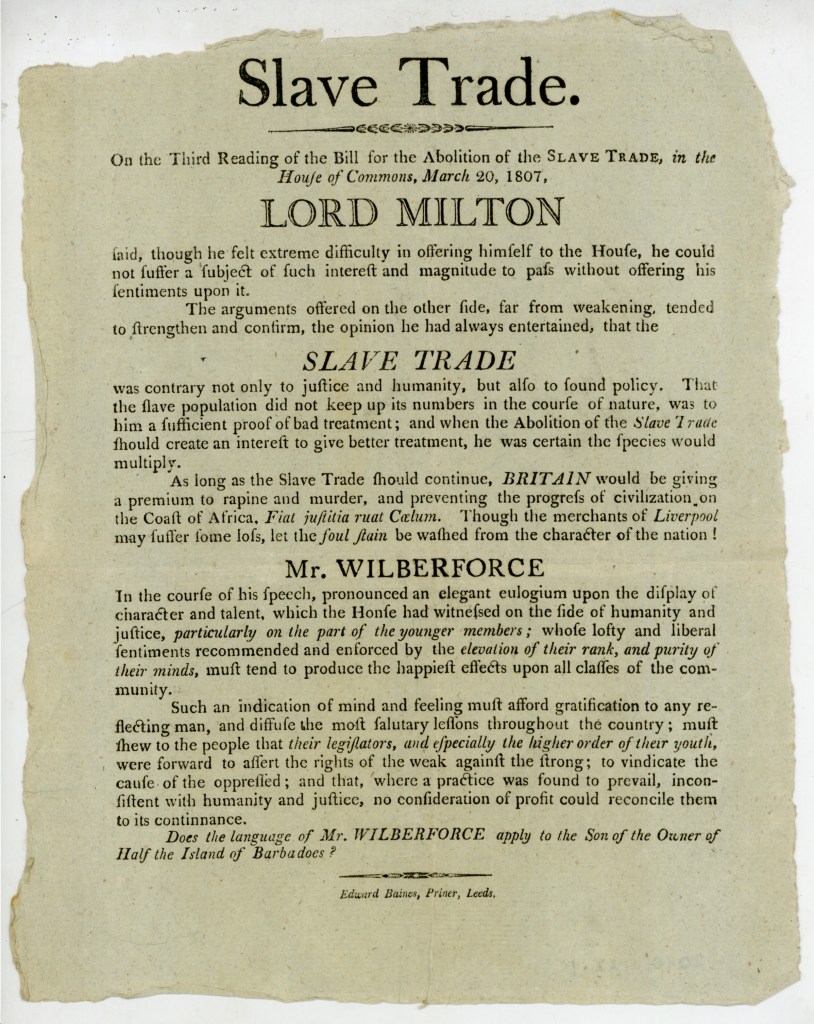

This handbill is interesting to me for a number of reasons. Firstly, it’s important to recognize that the publishing of this handbill, Edward Baines, was a prominent abolitionist in the city of Leeds, and that Milton and Wilberforce were opposing candidates in one of the most important elections in British history, the Yorkshire MP election of 1807. Wilberforce, an independent, was one incumbent, and Lord Milton was the Whig challenger to both him and the incumbent of the other seat, one Henry Lascelles, a Tory slaver and a plantation owner in Barbados. If you’ve been looking ahead at our list of article titles, you may have noticed that Part Three is specifically about the American Whig party. Well, it’s important to note here that William Wilberforce was not a Whig, and that in fact even though he agreed with Edward Baines on the issue of abolition, many of his other policies more closely aligned with Lascelles. The Georgian Society for East Yorkshire describes his political alignment in the election as an “independent Tory.”14

The history of elections in York is fascinating, and I would recommend this article if you want to learn more about them. The interesting thing to focus on here is the Whig rhetoric regarding the abolition of the slave trade, namely that “as long as the slave trade should continue, Britain would be giving a premium to rapine and murder, and preventing the progress of civilization on the Coast of Africa” (emphasis mine).

What Lord Milton refers to here is what was known as the Colonization Movement, spearheaded in the United Kingdom by the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. Many in the West may be aware that Sierra Leone and Liberia were both created as colonies for the ‘return’ of emancipated slaves to Africa by the UK and the US respectively; this was the movement that created those colonies. The Black Poor Committee had been created in 1786, but it wasn’t until the British Navy established a naval base at Freetown in 1803 in conjunction with the war with France that the colonization of Sierra Leone began in earnest. Prominent sponsors of the Committee included William Pitt and, of course, William Wilberforce. In these early years after the nominal abolition of domestic British slavery, many liberal thinkers in Britain advocated from freed slaves to be deported to Africa as a part of the broader colonial project, not in the least to assert a stronger British colonial claim in the face of French aggression.

This was hardly the only way in which the abolition of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade was an extension of the colonial project instead of a repudiation. In both Britain and America, the 1807 laws were passed not because they protected the “rights” of Black slaves, but because they calcified the pre-existing economic advantages of those who already owned slaves, allowing them to corner various parts of the early capitalist market. Alex Jones writes:

So, in 1807, when Napoleon imposed his blockade against European trade with Britain, plantation owners in the well-established (but heavily exploited) British sugar islands stepped in to support the Abolition of the British Slave Trade. This way they could stop the supply of slaves to the newer but more fertile plantations (Trinidad and British Guyana). This would protect them from being undercut by cheaper sugar in the British market. The Jamaican and Barbadian plantation owners were a strong lobby in Parliament, and their switching of sides was enough to tip the balance (Williams, 1944). The irony, that the British slave trade was abolished in part because slave plantation owners in Barbados and Jamaica, who already had all the slaves they wanted (the slave’s children ensured a steady supply), were scared that plantation owners in Trinidad and British Guyana may be able to undercut them if they were allowed to import more slaves.15

He comments further on the interchange between this and the birth of the British colonization movement:

In 1807, just as Napoleon declared [the Continental System blockade] on the UK and the UK abolished its slave trade, Henry Thornton, the director of the Sierra Leone Company, requested that the British Government assume full responsibility of the colony. He was concerned that, as a private sector venture, it was not financially viable, and it would not be able to subdue the increasing pressure for self-rule from the new settlers. Britain obliged Thornton’s request. On 1st January 1808, the small settlement of people that had started as a private sector venture 15 years earlier, was nationalised into a Crown Colony. With everything that was going on, it made sense for the Government to oblige Thornton’s request. It had recently established its new navy base and was in the process of setting up the new Court for the enforcement its abolition of the slave trade. There were also long-standing aspirations for increased trade with West Africa (which had been a key driver of the private sector enterprise to develop Freetown in the first place). It was seen as a potential competitor/alternative to the Caribbean as a source of imported materials for Britain. Given what was happening in Europe, it was in Britain’s interest to establish and maintain firm links with markets elsewhere around the world, whether in The Americas, Africa, India, China, Australia or the Pacific. Wherever the market, a safe haven in Freetown with a deep harbour would always be a useful stopping point from which to venture further.16

Once again we ask: what does any of this have to do with transfeminine literature? I’ll confess that these first two sections have mostly been signposting important historical trends and metrics that will help us to analyze innovations in transphobia and publishing discrimination down the line. There is a certain tendency in queer history to view it as a disconnected, perhaps emergent, phenomenon within the broader historical schema. Queer movements may be inspired by historical phenomena past, but they are never extensions thereof, nor does queer history feed back into the broader watershed of human development. A rigorous analytic of transfeminine literature proves itself to be anything but: the history of trans literature cannot be extricated from enslaved histories, Trans-Atlantic histories, or imperial histories, and we shouldn’t shy away from that in our critiques.

The reason I have gone to such lengths to demonstrate how Wilberforce and the British Empire were not acting out of a progressive abolitionist benevolence but a pragmatic and Imperial sensibility is because, at the end of this essay, I am going to claim that the same forces that abolished slavery in the British Empire were also responsible for the early criminalization of obscene literatures. A TERFish picture might thusly attempt to claim that the criminalization of trans literature has “always been a progressive goal,” or that British transphobia is somehow an anti-racist or anti-colonial project.

Both ideas are false and betray a lack of historical insight. The early criminalization of obscene literatures in the United Kingdom arose from a combination of the Evangelical moral sentiments we discussed in our first article and the reactionary dick-measuring contest with France which we have laid out in the two sections above. While the British abolition of slavery and the criminalization of obscene literature moved through the same broad social confluence, it is inaccurate to claim that the “reformation of manners” and the criminalization of trans speech was only made possible because of abolitionism or racial justice, or that one naturally followed out of the other. It is also inaccurate to claim that the British crusade against obscene literatures arose because of racism. If anything, anti-vice crusading against obscene literatures and British abolitionism were incidental to each other at best, tangential at worst.

I know that it’s an odd theoretical move to spend this much time outlining a historical ambivalence, but don’t underestimate the importance of staking this out. As we’ll extensively explore in Part Three and Part Four of this series, the American criminalization of cross-dressing and obscene literature was a deeply racist project, one invested in the calcification and preservation of chattel slavery. A reductionist view with the express political aim to, say, moralize against trans rights might take up this clear racial impetus behind the American system and contrast it against its murkier British cousin, and use that conversely to claim that British transphobia is far more progressive and that, if one simply removes race from the equation, transphobia actually would become a “feminist” or “social justice” issue. I would argue that this sort of sleight of hand is one of the primary reasons why TERFism has been so much more successful in the United Kingdom than in the United States across party lines.

Ultimately, the association of slavery with the criminalization of cross-dressing and obscene literatures is the most important factor in the development of social attitudes around the issue. Even in 1807, there was a broad sentiment among the Anglophone ruling class that slavery was a sin that would eventually need to be purged from the social conscience. While the criminalization of obscene literatures may not have caused the abolition of slavery or vice versa, the association between the two in the British Evangelical conscience via Wilberforcean moral ideals offers British transphobia a certain rosy moral glint to the British liberal that its distant American cousin severely lacks.

It also comes down to the geopolitical locality of slavery in the UK versus US in the period between 1807 and the American Civil War. The British Slave Trade Act of 1807 (nominally) abolished slavery within the British Isles and its various waters, while preserving it in its distant colonies. Conversely, the American Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves prohibited the foreign slave trade while preserving slavery in its home territory. We must recognize that, in this sense, Britain and America had not yet shaken off the vestiges of their relationship as colonizer and colony – neocolonialism at its finest. What this means is that for the British, there was a clear distinction between issues in the motherland and issues in the colonies. With the 1807 act, the issue of slavery had been neatly portioned off into the colonial sphere. By contrast, the issue of obscene publications was one marginal piece of a much broader moral and social reform movement that took place in the home sphere. As such, class, immigration, and religious bigotry would play a far larger role in the British criminalization of trans literature than race, as those were the issues animating the domestic politics of the Isles at the time (hence why William Wilberforce could be such an ardent advocate for the perils of enslaved peoples in the colonies while simultaneously supporting strict measures against the British lower class, religious minorities, queers, and immigrants at home). The United States had no such separation, and thus no clear bifurcation between the issues of cross-dressing, obscene publications, and slavery.

But that’s a topic for the next few articles.

The Vagrancy Act of 1824 and the Obscene Publications Act of 1857

Up to this point, I have been broadly trying to establish a baseline about the state of social issues at the turn of the 19th Century in the Anglophone sphere so that we can dive into the nitty gritty of the American criminalization of cross-dressing together without having to stop every five seconds to give broad-scale social context. Ultimately, the British side of this story has a lot less impact on the modern shape of transfeminine literature than the American side does. What this means is, at this point, we can take a speedy tour through the next few decades of British history without trying to give a comprehensive view of social trends at the time. The ultimate goal of this section is to A) provide useful context that’ll help to inform our discussion of the American criminalization of obscenity and B) give a broad picture of the connective tissue between the late 18th Century and the late 19th Century vis a vis the British criminalization so that we don’t have to massively backtrack when the UK becomes relevant again.

It is notable that around the start of the 1820s, Wilberforce fully shifted his attention away from the efforts to colonize Sierra Leone and toward the total abolition of slavery in the British Empire. In, he helped to found the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery Throughout the British Dominions, which was ironically responsible, among many other things, for the 1824 pamphlet by Elizabeth Heyrick “Immediate, not gradual abolition” and the publication of the first slave narrative by a black woman, The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, in 1831. The efforts of the Anti-Slavery Society combined with the upheaval cause by slave revolts in Jamaica during the Baptist War in 1831 and 1832 (mirroring revolts in Haiti prior) produced the conditions which allowed for slavery to finally be banned throughout the British Empire in 1833, then eventually fully implemented in 1838. Famously, Wilberforce died the week after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 passed the British parliament, adding a certain mythological sparkle to the accomplishment. The Herald wrote of his death: “Thus terminated the mortal career of as pure and virtuous a man as ever lived…”17 Certainly Wilberforce was one of the primary architects of the international demise of slavery. His moral accomplishments, however, are murkier terrain, and not necessarily so simple to track after the passing of the man himself.

At the same time that William Wilberforce was shifting his moral and political attentions from the British Parliament to a more radical abolitionism, the next important law in the history of transfeminine literature was passed, the British Vagrancy Act of 1824, which was primarily constituted to deal with a severe homelessness and immigration issue in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. The primary goal of the bill was Anti-Jacobin and Anti-French, but it also had as its secondary aim the regulation of prostitution. Roberts writes:

The fostering of family ties was also a large part of the message which moral reform leaders took with them when they moved into the world of moral destitution beyond the home base. […] [T]he particular disorders which reformers identified among the post-war urban labouring classes were usually linked to a general preoccupation with the stability of family life. Vagrancy, begging, prostitution, juvenile street crime: all might be brought under control if family life could be reestablished.18

One thing that I find very ironic about this is that Wilberforce was actually a staunch opponent of the Vagrancy Act, which he believed was far too draconian toward the homeless. Nevertheless, the Vagrancy Act of 1824 updated the Vagrancy Act of 1744 and reflected the standards of the time, including a new provision against the distribution of erotic publications that very much sounds like it could have been written by Wilberforce:

[E]very person wilfully exposing to view, in any street, road, highway, or public place, any obscene print, picture, or other indecent exhibition; every person wilfully openly, lewdly, and obscenely exposing his person in any street, road, or public highway, or in the view thereof, or in any place of public resort, with intent to insult any female […] shall be deemed a rogue and vagabond, within the true intent and meaning of this Act; and it shall be lawful for any justice of the peace to commit such offender (being thereof convicted before him by the confession of such offender, or by the evidence on oath of one or more credible witness or witnesses,) to the house of correction, there to be kept to hard labour for any time not exceeding three calendar months19

Like most of the legislation that criminalized obscenity in the first half of the 19th Century, the provision against obscene prints in the Vagrancy Act was only one insignificant detail ferreted away in a much larger bill. While it may not have explicitly labeled prostitution or erotica as its aims, the Vagrancy Act would be used to police both. Moreover, it came with a significant increase in the severity of the crime – once a minor charge, vagrancy was now sentenced with hard labor and imprisonment. Notably, about five days before the passage of the Vagrancy Act, Wilberforce fell extremely ill and was rushed away to the countryside.20 One must ponder, had he been well for the vote, if the bill would have passed in such an extreme form.

The aftershocks of the many wars with the French was the primary force behind the Vagrancy Act of 1824, and while its impacts may be less immediately obvious, anti-French sentiment also influenced the next law we need to talk about, the Offenses Against the Person Act of 1828. In 1791, one of the many actions of the French Revolutionaries had been to pass a new penal code which notably did not criminalize sodomy. While Napoleon did away with many of their innovations, the Napoleonic Codes upheld this refusal to criminalize sodomy, setting an incredibly important new precedent for the situation of homosexuals around the globe. Human Dignity Trust writes:

Spain and Portugal, for example, adopted similar laws inspired by the Napoleonic Code in 1822 and 1852 respectively, until Spain re-criminalised in the mid-20th century and Portugal in 1886. However, during their period of decriminalisation, these codes were exported to many Spanish and Portuguese colonies. The French Penal and Napoleonic Codes had a profound impact, directly and indirectly, on legal systems across the globe leading to the implemention of criminal codes that did not criminalise same-sex activity: Andorra (from 1791), Monaco (1793), Luxembourg (1795), Switzerland (some cantons in 1798 and nationwide from 1942), Belgium (1810 under French rule and 1830 upon independence), the Netherlands (1811 – this includes the Netherlands Associates of Aruba, Curaçao and St Maarten), the Dominican Republic (1822), El Salvador (1822), Brazil (1830), Bolivia (1832), Turkey (1858), Guatemala (1871), Mexico (1872), Benin (1877), Japan (1882, although it is recognised that Japan has largely never criminalised and the influence of the Napoleonic Code only stopped a very brief period of criminalisation), Paraguay (1880), Argentina (1887), Italy (1890), and Honduras (1899), Peru (1924), Poland (1932), the Philippines (1932), Denmark (1933) and Uruguay (1934).21

Obviously this list extends far beyond the relevant timeframe. What matters is that many of the most powerful members of the Continental System – France, Spain, and the Netherlands – were all engaged in this decriminalization of the crimes of sodomy and buggery around the timeframe in which this intense anxiety had arisen in British society about war refugees, continental immigrants, and vagrant violence. Much like the Vagrancy Act, the Offenses Against the Person Act of 1828 contained one statute about sodomy buried among dozens others – but that was precisely the goal of the Reform Movement. Up until this point, Common Law was still the most important metric of legality in the British Empire, i.e. decrees and royal edicts made by various royals over the centuries that formed the backbone of governance. One of the Reform Movement’s primary aims was the consolidation of the morass of Common Law into easily navigable and enforceable statutes that would provide a consistent criminal justice system. Lisa Surridge writes:

On 27 June 1828, the British Parliament passed into law the Offenses Against the Person Act. Known as “Lord Lansdowne’s Act” after the Home Secretary who introduced it in the House of Lords, it formed part of Sir Robert Peel’s sweeping reform of the criminal law achieved between 1825 and 1828. In those three years, parliament streamlined the criminal codes of the nation, repealing 278 piecemeal statutes and putting eight omnibus statutes in their place. Peel’s reforms clarified and consolidated the procedure in criminal cases and organised the laws governing evidence, theft, and offenses against the person. By 1830, when Peel left the Home Office, fully 75 per cent of criminal offenses were governed by legislation passed in the previous five years (Jenkins 27). The reforms reflected Peel’s core beliefs: that the law “should be as precise and intelligible as it can be made” (Hansard 1214-15) and that the legal code defines “the moral habits of the people” (1214). Historian Gregory Smith hails the 1828 Act as “the first truly comprehensive piece of legislation designed to address interpersonal violence in British society” (58). Unlike many previous pieces of legislation establishing the nation’s criminal code, it was not inspired by a particular crime but by an urge to clarify and simplify the legal code itself.22

And to be clear – this was an enormously progressive bill that laid down many core foundations for our modern law. It streamlined the British Justice System, made it way easier for women to seek help with domestic abuse, and made the first equivocation between the attempt to commit a crime and the actual committal thereof. Unfortunately, it also narrowed the definition of sodomy and buggery to homosexual intercourse and made the sentence for that crime the death penalty.

I want to keep in mind this trend of seeking to reform Common Law by producing comprehensive statutes to explicitly govern moral and civil behavior – it’ll become relevant again in Part Four of this series.

By the early 1830s, Reformism had gone from a pet project of men like Wilberforce to a sweeping social movement that had completely reshaped British society. Perhaps the two capstone pieces of legislation during this period were the Reform Act of 1832 and the Abolition of Slavery Act of 1833. We’ve already discussed the latter, so I want to turn your attention to the former – not because of what the bill was about (very little to do with obscene publications), but because of how the efforts to pass it were responsible for the political rise of the next Dead White Dude who’s responsible for the current state of discrimination in trans publishing, one Baron John Campbell. There were multiple attempts to pass the Reform Bill, which eventually managed to squeak through because the Tories fell out of power, and though his famous 1831 speech came for a version of the bill that didn’t ultimately pass, I still find it illustrative of this man and his legislative priorities:

The House of Commons was intended by the Constitution to represent the people, and be returned by the people; and the true principle of the Constitution, was laid down in the writs issued by Edward 1st. Quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbatur. All the people, according to that, ought to have a voice in the election of their Representatives. He admitted that in those summonses the principle of Universal Suffrage was laid down, and upon him and upon those who objected to Universal Suffrage was cast the onus of proving that Universal Suffrage would lead to inconvenience. He was prepared to show, that Universal Suffrage would lead to great inconvenience, monstrous ruin, and universal destruction. But still there was a medium between Universal Suffrage and giving the right to particular individuals to return Members to that House. He saw no reason why the numbers of that House should not be reduced, and he could not agree with some hon. Members in thinking the hon. and gallant General’s motion of little importance. If, however, that motion should be agreed to, he hoped that the Reform Bill would still be allowed to pass, for he was confident that great benefit would be conferred on the country by that measure.24

“Great inconvenience, monstrous ruin, and universal destruction” – remember that. It should also be noted that passing this Reform Bill was directly responsible for getting this man elected to office in 1832, as the constituency he represented, Dudley, had not previously had an MP. Ronald Pearsall gives us a rather droll description of Campbell’s career between his entry to Parliament in 1830 and the passage of the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, commonly known as Lord Campbell’s Law, which is the final piece of legislation we’ll be discussing in this essay:

Industrial times threw up a different kind of justiciary – the middle-class man who had done well in business and was something of a zealot, and who knew what he liked and could pick out smut at a hundred paces. The Obscene Publications Act of 1857 held that magistrates throughout the country had the power to order the destruction of “any obscene publications held for sale or distribution on information laid before a court of summary jurisdiction. The man who was responsible for this act was Lord Campbell, a learned and industrious gentleman who made up for his lack of sparkle with glum determination. […] He put in sterling work on projects that less enthusiastic members shirked – the Fines and Recoveries Abolition Act of 1833, the Inheritance Act and the Dower Act of the same year, the Wills Act of 1837. His main admirable object, however, was to get rid of the cumbersome technicalities that bogged down the law in primeval mire. He became Attorney General in 1834, and speedily took action against the bookseller Hetherington for blasphemous libel, an action he blithely justified on the ground that “the vast bulk of the population believe that morality depends entirely on revelation; and if a doubt could be raised among them that the ten commandements were given by God from Mount Sinai, men would think they were at liberty to steal, and women would consider themselves absolved from the restraints of chastity.” This extraordinary statement is one of the clearest demonstrations of the view that morality has no real existence, but is dependent on the fear of divine chastisement. […] As the Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench he was inclined to histrionics […] and he was accused – as a Chief Justice should not be – of unduly influencing the juries, as well as concealing purple passages for gallery applause. Here was the man who made himself arbiter of the fate of literature. He was not the kind of person to be thwarted by the difficulty of defining obscenity. 25

Oh, and lest you think that the man was not influenced by Wilberforcean ideals – he very much was. In his autobiography, he writes of his formative experiences hearing of Wilberforce’s work on abolition:

At five Wilberforce rose and the deepest silence prevailed. He was heard with a mixture of admiration and reverence. His genuine sincerity, his perfect disinterestedness, his devotedness to the cause, his exalted tone of morality, his deep religious feelings, gave a solemnity and sacredness to his manner which, united with his persuasive reasoning, his playful imagination, his easy elocution, and his musical voice, carried enthusiastic conviction and rapturous delight into the breasts of all present who were uninfluenced by sordid motives for countenancing the traffic ; and dismay, shame, and almost remorse, into the hearts of those who, from a love of private gain or a dread of injury to the public from loss of commerce, had steeled themselves against the dictates of reason and humanity. […] The motion was lost by a majority of four, the amount of which was probably arranged by George Rose, the Secretary to the Treasury, with a view of saving the slave trade and keeping up the hopes of the abolitionists and the credit of the Minister. After hearing this debate I could no longer have been satisfied with being ‘Moderator of the General Assembly.’26

Call me crazy, but I’m pretty sure he liked the guy.

John Campbell would be responsible in 1857 for passing Britain’s first major obscenity act, the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, which made the publication of erotic literatures a statutory offense for the first time. Colin Manchester describes the character of the act in his article “Lord Campbell’s act: England’s first obscenity statute,” where he observes:

Legislative attention was initially confined to dealing with specific aspects of obscenity such as indecent displays and importation through customs and excise, with provisions being incorporated into statutes dealing essentially with other matters. Whilst these measures went some way toward combatting the pornography trade, they had only a limited impact. The 1857 Act was different, for it aimed to systematically put down the trade by introducing new powers enabling police constables to seize obscene material and seek its destruction before magistrates.27

Of course, the Society for the Suppression of Vice had been repeatedly petitioning and lobbying for the creation of this sort of legislation for over half a century by this point. So, what changed? I’ll give you one guess. One guess.

Yup – it’s the goddamn French again. Naomi Wolf observes:

France, the source of alarming revolutionary influences, experienced its own backlash against freedom of speech. In the spring of 1857, the great French novelist Gustave Flaubert was prosecuted in Paris. His offense was having published sections of the novel Madame Bovary in serialized form in La Revue de Paris […] The charge was “outrage to public and religious morals and to morality” and “offending public mores.” […] All the men were acquitted – but the trial left its mark. […] The trial established for the modern state that there was such a secular thing as “public mores” or “public order,” and that books could threaten this new thing. The idea, codified in modern form in France in 1857, was further adapted and developed in England and ultimately reached the United States. It has endured in similar phrasing as a legal concept to this day. […] The Obscene Publications Act of 1857 was a watershed piece of legislation. The bill gave magistrates power to confiscate material deemed obscene, but it failed, just as opposing peers had feared, actually clearly to define “obscenity.” Decisions as to what crossed the line were left to the cool or the fervid imaginations of magistrates. Because of this legislation, the professions of writer, editor, publisher, and bookseller had become tangibly more dangerous28

The passage of this Act was a major victory for the Society for the Suppression of Vice, and that its passage seems to bring up an intellectual legacy of Wilberforce’s within the law. Natalie Pryor writes:

The Society for the Suppression of Vice was instrumental in both officially and unofficially targeting what they considered to be obscene publications, and was one of a number of bodies founded in the half century immediately prior to the passing of the 1857 Act concerned with influencing social change and action in the interest of public decency. The Society saw literature as just another means by which public order and the decency of the common man could be disturbed, hence its desire to regulate literary output and availability. In his article ‘Lord Campbell’s Act: England’s First Obscenity Statute’, Colin Manchester sets out how the Society for the Suppression of Vice and the Proclamation Society operated in the first half of the century before official censorship legislation was passed. Manchester draws attention to their relationship with the Church, and exposes how they utilised legislation such as the 1824 Vagrancy Act to target pornography above and beyond the contemporary libel laws that were in place; however, Manchester also draws attention to the fact that the Society of the Suppression of Vice rarely prosecuted cases where there was doubt over the outcome, leading to questions over the accomplishments the Society credited itself with. The advent and passing of the Obscene Publications Act did not limit their influence or desire to be involved in literary prosecutions. Instead, the Society appeared to be ahead of the legislators, recognising that it was the publication of literature that needed to be its focus, going straight to the source of the problem by focusing its efforts on the distribution, and, later on, the reading of such texts.

When the legislation came into effect, the Society took on a different role. In the two cases of Adolphus Henry Judge and Dr. John Galt in the 1860s, the Society for the Suppression of Vice itself prosecuted these alleged distributors of obscene and pornographic work on behalf of the Crown, due to a lack of public funds, using their own solicitors, Messrs. Pritchard and Ollette. According to the society’s official advertisements, one of which appeared in an 1872 volume of The Leisure Hour, they took on the responsibility of prosecuting obscene works as ‘there are no funds at the disposal of Government and the police applicable to such purposes, and the country does not in these prosecutions allow any part of the expenses.’ The Society for the Suppression of Vice mainly gained its funding through private donations and subscriptions of primarily middle-class gentlemen who found themselves concerned about the moral wellbeing of the public. Interestingly, they also received funding for their prosecutions against obscene literature from authors, such as the Reverend Charles L. Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll made regular annual payments to the Society to support their cause, as recorded in the ledgers that he kept of his financial accounts.29

While he may not have lived to see the fruits of his labor as with his abolition efforts, it seems evident to me that the evolution of the Vice Society in England from a small group of concerned citizens dedicated to an obscure royal declaration to a vigilante privately-funded quasi-police force that was actively involved in the prosecutions of multiple obscenity cases across the 1870s and 1880s (see here for another one) is not a betrayal of Wilberforce’s vision for the group but a manifestation of it. This model of prosecution should also sound very familiar to anyone following the ongoing waves of trans book-bannings in the West. It is a blueprint that the Evangelical movement has refined and perfected over the centuries, distilled down to the point where a single private citizen’s surveillance of a literature they find distasteful can result in that book or publication being struck from the record altogether.

While William Wilberforce may have provided the initial sparks and community organizing for the various moral objectives of the Vice Society, by the time that John Campbell passed the Obscenity Act, they had passed into the annals of British culture and taken upon a life of their own. Even though the original roots of these laws were largely incidental or even accidental, over the course of several decades (and a movement dedicated to streamlining and rewriting the laws for an entire Empire), what began as sub-clauses and riders evolved into a fully-fledged piece of legislation designed to criminalize and destroy illicit literatures. To be very clear, laws like these are why it is nearly impossible to trace transfeminine literature back through the 19th Century – the mere discovery of an erotic text was stable grounds for its incineration, which eliminated both the possibility of the record-keeper and the ability of underground authors to pass down their work.

That is why we don’t have a significant corpus of trans literature from the 1800s.

It’s entirely possible that there were entire communities of transfeminine writers in London producing fiction during this time. But we have no way to confirm or deny, because that information was deliberately, maliciously expunged from the record with the explicit intent to make it impossible for anyone to ever read again. It’s centuries gone, and bar an absolute miracle, that’s invaluable historical record that we’re never gonna get back.

Only fragments remain to piece together the absence of what our ancestors left behind.

This is Part Two of an eleven-part series on the historical development of transfeminine literature. Part Three, “American Evangelicalism and the Ineptitude of the American Whig Party,” can be read here.

A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature

- Part One: The Moral Origins of Obscenity

- Part Two: Trans-Atlantic Relations and the Obscene Publications Act of 1857

- Part Three: American Evangelicalism and the Ineptitude of the American Whig Party

- Part Four: The Birth of American Anti-Trans Law

- Part Five: Petticoat Punishment and the Comstock Act of 1873

- Part Six: Continental Erotica, Magnus Hirschfeld, and the Nazis

- Part Seven: Virginia Prince and the ‘Invention’ of the Transfeminine Press

- Part Eight: Jan Morris and the Conundrum of the Transsexual Author

- Part Nine: Transfeminine Publishing and the Digital Revolution

- Part Ten: Topside Press, Nevada, and the ‘Transgender Tipping Point’ Myth

- Part Eleven: Detransition, Baby, the Pandemic, and Transfeminine Publishing Today

Reading List

Primary Texts

- The Declaration of Independence of 1776 (United States)

- Constitution of 1787 (United States)

- Le code pénal de 1791 (France)

- Le Code civil des Français de 1804 (France)

- “From Thomas Jefferson to United States Congress, 2 December 1806” – Thomas Jefferson (1806)

- “Slave Trade.” – Edward Baines (1807)

- Slave Trade Act of 1807 (United Kingdom)

- Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 (United States)

- “The Monroe Doctrine” – James Monroe (1823)

- Vagrancy Act of 1824 (United Kingdom)

- “Immediate, not Gradual Abolition” – Eliza Heyrick (1824)

- Offenses Against the Person Act of 1828 (United Kingdom)

- “Speech to the Parliamentary Reform Bill Committee” – John Campbell (1830)

- Reform Act of 1832 (United Kingdom)

- Abolition of Slavery Act of 1833 (United Kingdom)

- William Wilberforce’s Obituary in The Herald (1833)

- Obscene Publications Act of 1857 (United Kingdom)

Secondary Texts

- Life of John, Lord Campbell – Mrs. Hardcastle (1881)

- The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Overture and the San Dominogo Revolution – C.L.R. James (1938)

- “Lord Campbell’s Act: England’s First Obscenity Statute” – Colin Manchester (1988)

- The Worm in the Bud: the World of Victorian Sexuality – Ronald Pearsall (2003)

- Making English Morals: Voluntary Association and Moral Reform in England, 1787-1886 – M. J. D. Roberts (2004)

- “The Bicentennial Commemorations: The Dilemma of Abolitionism in the Shadow of the Haitian Revolution” – Claudius Fergus (2010)

- “Interchange: The War of 1812” – Cleves, Eustace, et al. (2012)

- “The British View the War of 1812 Quite Differently Than Americans Do” – Amanda Foreman (2014)

- “The 1857 Obscene Publications Act: Debate, Definition and Dissemination, 1857-1868” – Natalie Pryor (2014)

- Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love – Naomi Wolf (2020)

- “The Great Yorkshire Election Of 1807” – David Neave (2020)

- “Why did Britain colonize Freetown? 1803-1815” – Alex Jones (2020)

- “A History of LGBT Criminalization” – Human Dignity Trust (2024)

- “WILBERFORCE, William (1759-1833), of Gore House, Kensington, Mdx. and Markington, nr. Harrogate, Yorks” – David R. Fisher (Accessed 2024)

- “On the Offenses Against the Person Act, 1828″ – Lisa Surridge (Accessed 2024)

- Danachos. “Haudenosaunee Territory.” January 10th, 2018. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Haudenosaunee_Territory.png Danachos, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons ↩︎

- Jefferson, Thomas. The Declaration of Independence. 1776. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript ↩︎

- Sidenote: I have always been fascinated by Jefferson’s claim that the Indian Savage is an “undistinguished destruction [of] sexes”. But that’s a topic for another article. ↩︎

- “1803 Louisiana Purchase.” Compromise of 1850 Heritage Society. Accessed September 6th, 2024. http://www.compromise-of-1850.org/1803-louisiana-purchase/ ↩︎

- Cleves, Rachel Hope, Nicole Eustace, Paul Gilje, Matthew Rainbow Hale, Cecilia Morgan, Jason M. Opal, Lawrence A. Peskin, and Alan Taylor. “Interchange: The War of 1812.” The Journal of American History 99, no. 2 (2012): 520–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44306807. 526-527. ↩︎ ↩︎

- Foreman, Amanda. “The British View the War of 1812 Quite Differently Than Americans Do.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 2014. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/british-view-war-1812-quite-differently-americans-do-180951852/ ↩︎ ↩︎

- Monroe, James. “The Monroe Doctrine.” 1823. ↩︎

- FERGUS, CLAUDIUS. “The Bicentennial Commemorations: The Dilemma of Abolitionism in the Shadow of the Haitian Revolution.” Caribbean Quarterly 56, no. 1/2 (2010): 145-46. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40654957. ↩︎

- James, C.L.R. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Overture and the San Dominogo Revolution. London: Secker and Warburg Ltd., 1938. 53-54. https://politicaleducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/CLR_James_The_Black_Jacobins.pdf ↩︎

- Martinet, Aaron. Incendie de la Plaine du Cap. Massacre des Blancs par les Noirs. 1833. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Incendie_de_la_Plaine_du_Cap._-_Massacre_des_Blancs_par_les_Noirs._FRANCE_MILITAIRE._-_Martinet_del._-_Masson_Sculp_-_33.jpg ↩︎

- Constitution of the United States of America, Article I, Section IX, Clause I. ↩︎

- Jefferson, Thomas. “From Thomas Jefferson to United States Congress, 2 December 1806.” 1806. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-4616 ↩︎

- Baines, Edward. “Slave Trade.” 1807. mylearning.org. Accessed September 6th, 2024. https://www.mylearning.org/stories/william-wilberforce/194 ↩︎

- Neave, David. “The Great Yorkshire Election Of 1807.” The Georgian Society of East Yorkshire. November 2020. https://www.gsey.org.uk/page/1222/the-great-yorkshire-election-of-1807.html ↩︎

- Jones, Alex. “Why did Britain colonize Freetown? 1803-1815.” Medium, May 23rd, 2020. https://alex-jones.medium.com/britains-colonisation-of-sierra-leone-the-point-of-infection-6d74bedd29d0 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “William Wilberforce Obituary.” The Herald. August 3rd, 1833. Cited by mylearning.org, https://www.mylearning.org/stories/william-wilberforce/194 ↩︎

- Roberts, M. J. D. Making English Morals: Voluntary Association and Moral Reform in England, 1787-1886. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. 124. ↩︎

- Vagrancy Act, 1824. https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1824/act/83/enacted/en/print.html ↩︎

- Fisher, David R. “WILBERFORCE, William (1759-1833), of Gore House, Kensington, Mdx. and Markington, nr. Harrogate, Yorks.” The History of Parliament, Accessed September 6th, 2024. http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/member/wilberforce-william-1759-1833 ↩︎ ↩︎

- “A History of LGBT Criminalization.” Human Dignity Trust. August 27, 2024. https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/a-history-of-criminalisation/ ↩︎

- Surridge, Lisa. “On the Offenses Against the Person Act, 1828.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. September 27th, 2024. https://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=lisa-surridge-on-the-offenses-against-the-person-act-1828 ↩︎

- Woolnoth, Thomas. John Campbell, 1st Baron Campbell of St. Andrews. Date Unknown. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Campbell,_1st_Baron_Campbell_of_St_Andrews_by_Thomas_Woolnoth.jpg ↩︎

- PARLIAMENTARY REFORM BILL COMMITTEE—ADJOURNED DEBATE.

HC Deb 19 April 1831 vol 3 cc1609. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1831/apr/19/parliamentary-reform-bill-committee#column_1609 ↩︎ - Pearsall, Ronald. The Worm in the Bud: the World of Victorian Sexuality. London: Stroud, 2003. 382-384. https://archive.org/details/worminbudworldof0000pear_j3z4/page/382/mode/2up ↩︎

- Mrs. Hardcastle. Life of John, Lord Campbell. London: John Murray, 1881. 34, 36. https://archive.org/details/lifeofjohnlordca01campiala/lifeofjohnlordca01campiala/page/36/mode/2up?view=theater ↩︎

- Manchester, Colin. 1988. “Lord Campbell’s Act: England’s First Obscenity Statute.” The Journal of Legal History 9 (2): 223. doi:10.1080/01440368808530932. ↩︎

- Wolf, Naomi. Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love. London: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2020. 36-37, 39-40. ↩︎

- Pryor, Natalie. “The 1857 Obscene Publications Act: Debate, Definition and

Dissemination, 1857-1868.” Master’s Thesis, University of Southampton, 2014. 27-28. ↩︎

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.