This is the second essay in our A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature series. You can find the first essay “The Moral Origins of Obscenity” here, the previous essay “Trans-Atlantic Relations and the Obscene Publications Act of 1857” here, or a complete series listing at the end of the essay.

The Slavery Question

One cannot parse the history of the United States in the 19th Century without the crystalline understanding that “The Slavery Question,” as the infamous 1860 editorial written by one of Alexander Hamilton’s descendants for the New York Times proclaimed it on July the 4th, infused every aspect and quarter of American life:

As we have hitherto insisted, [The Presidential Election of 1860 election between Lincoln and Douglas] is simply a struggle of contending sections for power. Possession of the Federal Government is what both North and South are striving for. But there is a motive for this contest on both sides – and the leading motive of the South is a determination to regard Slavery as their paramount interest, and its protection and perpetuation as their settled policy. They have invented the doctrine that slaves are made property by virtue of State laws; – that they are recognized as property by the Federal Constitution; – that they may, therefore, be taken, held, and treated as property in every territory and other part of the United States where the Constitution is the supreme law; and that the Federal Government is bound to protect their owners in the possession and control of this property, whenever the Territorial Government shall fail to do so. If this position can once be established, the slaveholding interest becomes at once and forever the controlling interest of the Government.1

The calcification of the slaveholding interest succeeded in part during the 1860s, but continues in the United States to this present day. Those who’ve read the Constitution will know: slavery has yet to be fully abolished in this country. This is the full text of the Thirteenth Amendment, i.e. the one that partially abolished slavery:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. (Emphasis mine)2

The events leading up to the American Civil War are deeply unpleasant theoretical terrain, rife with genocide, violence, and dark politics that still shape our country today. It is also, thanks to the efforts of Lost Causers, very much a contested topic, and there’s a lot of misinformation on the internet about it. Unfortunately for us, this is the primary context out of which the criminalization of cross-dressing and obscene literatures arose in the United States. I have done my best to portray events with rigorous historical analysis resistant of anachronism or narrativisation, but know that any modern account of the Antebellum Period is a fraught endeavor, and that I have here only laid out a small fragment of a much broader social picture of the time.

What is abolition? We’ve been talking about it for the last two articles, but we haven’t taken the time to sit down and hash out the actual details. Abolition is the end of slavery, yes, but what does that mean in a country where slavery has never ceased? How do we understand abolition in the context of a carceral state that, now more than ever, has become increasingly shameless about using its racialized inmates for forced labor? How do we understand abolition in a world where being trans can be the grounds to have your freedoms and opportunities stripped from you, where trans women of color and trans sex workers are disproportionately discriminated against by the police, the state, and the prison industrial complex?

We talk about abolition as a ‘historical movement,’ but the real reason I’ve taken so much time to stake out the origins of transfeminine literature in these historical movements and patterns is because the real issue at stake is thinking abolition NOW, today, through our literatures and our actions. In her book Abolition. Feminism. Now., Angela Davis writes:

We attempt here to distinguish between a purely analogical relation between slavery and imprisonment and one that acknowledges a genealogical connection between the two institutions. It is within the context of highlighting the historical influence of the system of slavery […] that we trace the past convergences of abolition and feminism within the antislavery movement. White women, for example, developed a consciousness of their own collective predicament by comparing the institution of marriage to slavery without attending to the violences perpetuated by their own actions and inactions. Moreover, we may want to consider that the very term feminism, an anglicization of the French feminisme, has its origin within the tradition of utopianism associated with Charles Fourier, who interpreted the social condition of women as a form of slavery. There are some aspects of the relationship between the antislavery and anti-prison movements and the political moments in which they occurred that have yet to be brought into a conversation that acknowledges the pitfalls and potential of feminism.3

As we outlined in Parts One and Two of this series, the criminalization of obscenity and illicit literatures in the United Kingdom was a small piece of a much broader social movement to reform and centralize the British criminal justice system, a movement whose history cannot be extricated from the issues of slavery, colonialism, and imperial mandate occurring at the same time. This goes doubly so for the United States. Anti-trans discrimination in publishing is a carceral issue, as it has its historical roots in the censure, indictment, imprisonment, and execution of those who trespassed moral bounds, and in this sense, it cannot be understood beyond the context of abolition. The core goal of this article is to lay the extensive groundwork for Part Four of this series, which will be diving into detail as to how, where, and why cross-dressing was first criminalized in the United States, how it interwove with the Slavery Question, and why it’s still relevant today.

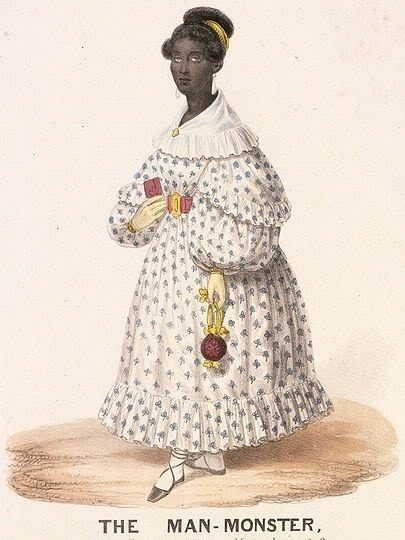

There are two primary reasons why this history matters for contemporary transfeminine literature. Firstly, the Antebellum period is when we begin to see the economic model for trans publishing emerge. In the mid-20th Century, mail-based orders and subscriptions were the primary means of organization and dissemination for many transsexual and transvestite groups, and the earliest ancestors of the TG/TF (Transgender/Transformation) fiction genre would arise from those networks. My argument will lay out A) how the mail-based publishing model arose in the US, and B) how slavery, anti-abolitionism, and the criminalization of obscenity in the 1830s and 1840s cannot be extricated from the social confluences that caused it. Transvestism through the mail was not a historical accident – in fact, as I’ll demonstrate later in this argument, publishers of cross-dressing lithography were some of the first people implicated by anti-obscenity law in the United States.

Secondly, this article will attempt to understand how issues of obscenity, cross-dressing, and slavery moved and interlocked through the American political and economic sphere during the first half of the 19th Century. Our goal is not only to understand why cross-dressing was criminalized, but also who and what was responsible for that criminalization. Critically, I will argue in this essay that while the American Whig Party was often a driving force behind “moral reform,” the primary cause of the criminalization of obscenity and cross-dressing in the United States was not the moral crusades of the Evangelical which we discussed in Parts One and Two, but rather the economic imperatives of the Southern slaveholder, which operated through both the Whig (predominantly Evangelical) and Democratic (predominantly not Evangelical) Parties alike. In this sense, early sentiments against transvestism and cross-dressing in the United States appear not to be items on the Evangelical moral agenda insomuch as signifying dogwhistles for political and economic discourses around the enslaved body. The crucial takeaway is that there is a significant historical divergence between British and American obscenity law that vividly reemerges as a genre schism within transfeminine literature from the 1890s into our present day.

This conversation matters beyond these historical specifics, though. In the coming months and years, I’m going to be using this blog to interrogate white carceral feminism, and specifically white carceral transfeminism, or the criminalization of “obscene” trans literatures have produced certain adaptations within the themes and characters of the white transfeminine author which uphold the legal and moral imperatives of neo-slavery that continue in the Western world to this day. The goal of this entire article series is to give the lay reader a solid grounding in these issues of abolitionism, both so that they can recognize the flaws in trans literature for themselves, and so that we can refer back to this scholarship when truly analyzing the contemporary state of the genre and industry. Abolition is an issue that should be at the forefront of the transliterary imagination, but too often, I have found that white trans ‘feminist’ novels fail to address or even acknowledge it in any meaningful way.

I don’t think this occurs out of malice or bad faith in most circumstances. I would largely attribute it to ignorance on the part of the white trans author and a lack of accessible information on the issue, only exacerbated by the systemic barriers which many transfemmes, especially trans women of color, face toward receiving higher education. My hope is that this article series can provide some measure of balm to both wounds.

Tracing this genealogy of slavery, obscenity, and transphobia is our goal, and to achieve it, we need to return to the beginning of the 19th Century and the end of the War of 1812 in the United States.

The Economic Fabric of American Evangelicalism

While William Wilberforce (see Parts One and Two) was not as famous in the Americas as he was in the United Kingdom, the movement of moral reform, abolitionism, and social Evangelicalism which he prominently represented was. In Britain, it may have taken the form of the Society for the Suppression of Vice and the other reform movements of the early 1800s. But in the United States, this peculiar conflux of moral reform and abolitionism was known as the Second Great Awakening.

Now, when I started writing this article, I hadn’t yet realized that people may not have a concrete understanding of what an “Evangelical” is. To fully unpack this history, we’re gonna need to get into the nitty gritty of what Evangelicals believe, and why they hold those beliefs, so allow me a moment to offer some definitions for those who may not know. Evangelicalism is a movement within Protestant Christianity, often distinguished by specific Churches or movements that have Evangelical practices, i.e., denominations that evangelize, that prioritize conversion or preaching. For a definition in the broadest sense, Merriam Webster can give us a solid understanding of what we’re working with here: Evangelical faith emphasizes “salvation by faith in the atoning death of Jesus Christ through personal conversion, the authority of Scripture, and the importance of preaching as contrasted with ritual.”5 Ritual takes place within the bounds of a church or a holy place; what distinguishes Evangelical “action” is that it extrapolates Protestant Christianity beyond the steeple, framing it as a moral model for any societal action. To be an Evangelical, thus, means not just acting through the Church through mission and dogma, but acting through all other institutions which govern a potentially religious life: the State, the School, the Home, and the Law (for those looking for more context, this Atlantic article is a good read).

In this sense, the project of American Evangelicalism has always deeply invested itself in the manipulation and instrumentation of Democratic institutions, seen as one more arm in the execution of Christ’s plan for the country (the theocratic state) and thus the world. Moreover, it’s crucial to recognize that an Evangelical viewpoint has always taken a multi-pronged approach and sought to accomplish its goals through many institutions. Politics, economics, society, missionary work – all fold together into a single operating principle. This has been most extensively written upon as it pertains to the deep interconnexions between capital and faith; Max Weber describes this as “the protestant ethic,” i.e. the spirit of the Protestant faith which animates the project of Capitalism, and he also lampshades the primary political schism which this essay seeks to understand:

Thus the capitalism of to-day, which has come to dominate economic life, educates and selects the economic subjects which it needs through a process of economic survival of the fittest. But here one can easily see the limits of the concept of selection as a means of historical explanation. In order that a manner of life so well adapted to the peculiarities of capitalism could be selected

at all, i.e. should come to dominate others, it had to originate somewhere, and not in isolated individuals alone, but as a way of life common to whole groups of men. This origin is what really needs explanation. Concerning the doctrine of the more naïve historical materialism, that such ideas originate as a reflection or superstructure of economic situations, we shall speak more in

detail below. At this point it will suffice for our purpose to call attention to the fact that without doubt, in the country of Benjamin Franklin’s birth (Massachusetts), the spirit of capitalism

(in the sense we have attached to it) was present before the capitalistic order. There were complaints of a peculiarly calculating sort of profit-seeking in New England, as distinguished from other parts of America, as early as 1632. It is further undoubted that capitalism remained far less developed in some of the neighbouring colonies, the later Southern States of the United

States of America, in spite of the fact that these latter were founded by large capitalists for business motives, while the New England colonies were founded by preachers and seminary graduates with the help of small bourgeois, craftsmen and yoemen, for religious reasons. In this case the causal relation is certainly the reverse of that suggested by the materialistic standpoint.6

In our modern depictions of Antebellum period, we often frame the conflict of “North vs. South” as a fight between the forces of slavery and the forces of abolition. This is mostly wrong. It is much more accurate to describe it as a tug-of-war between two sharply diverging economic pictures of the new nation: an agrarian economy ruled by chattel slavery versus a new capitalistic economy ruled by the newly industrialized powers of the North.

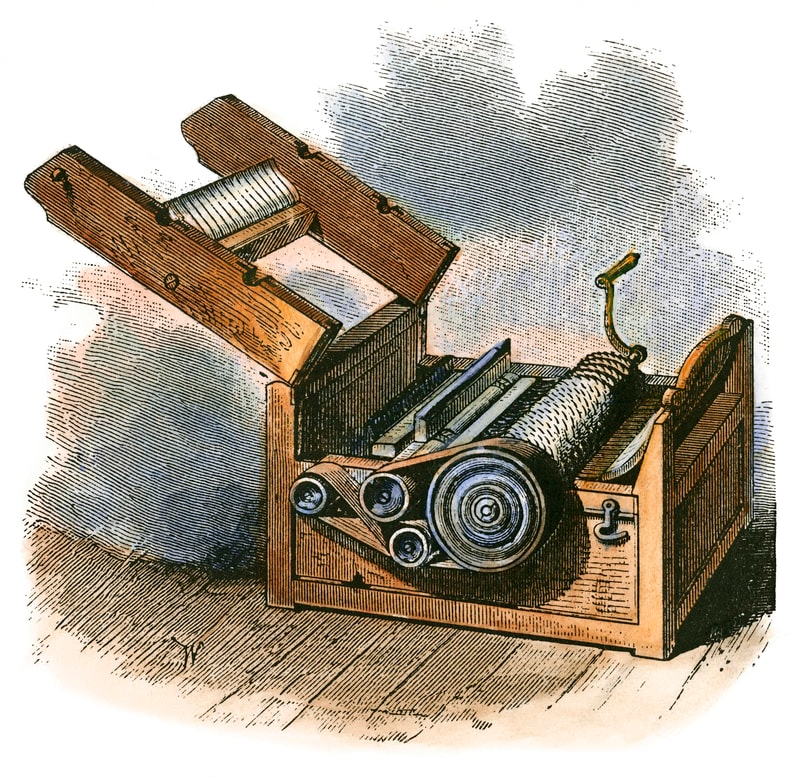

This was a conflict not only spurred by industrialization, but created by it. In 1793, American inventor Eli Whitney created arguably the most important invention in early American history: the cotton gin, which completely revolutionized how cotton was prepared for shipment and processing. For those who didn’t grow up in the American South and have never seen a cotton plant before, freshly harvested cotton is filled with dozens of spiky seeds which need to be removed before it can be woven into cloth. Before the cotton gin, this was a massively labor-intensive process, one which much of the budget of a cotton plantation would have to be directed toward. With the advent of the cotton gin, though, the economic calculus for Southern plantation owners was flipped upside down. Overnight, processing cotton went from a task that skilled laborers would have to painstakingly focus on for hours to a simple chore that could be performed with machines. What this meant was that rather than focusing on acquiring better laborers and investing in their skills, Southern plantation owners could instead focus on more laborers – more laborers, cheaper laborers, and of course, the maximum amount of possible land to maximize potential profits. And the cheapest way to acquire labor? Well, if you owned enough slaves, you wouldn’t have to pay for any labor at all.

A good historical rule of thumb: if you want to understand what caused a historical development, follow the money. Who bought Southern cotton? Britain. During the 1820s, an astonishing 48% of the value of all American exports came from selling cotton back to Europe7. The textile industry was one of the largest in the world in the first half of the 19th Century, and Britain made every attempt to monopolize the processing and production thereof, while outsourcing all of the growing to its colonies. That was a basic metric of the British economy during this period: the “Old Colonies” produced the cotton, and then British factory owners profited on it. The dependence upon this trade economy became so great that during the American Civil War, the Confederacy tried to embargo sales to the United Kingdom in an effort to win their support in the war, leading to what has been called the “Cotton Famine” in industrial parts of the UK. In essence, the entire Southern economy depended on neocolonial exchange between colonizer and former colony, as the British demand for raw cotton was the hinge upon which the fortunes of the entire region swung.

On the other side of the coin, the Northern industrial approach was also deeply informed by their relations with the British – but rather than the lucrative trade partnership of Southern plantation owners, here it was far more tied to tyranny and strife. In 1767, Britain passed the Townshend Acts, a series of taxation laws premised upon the idea that the Americans needed to repay the British for their assistance during the French and Indian Wars. Most Americans will be familiar with the archetypal response to this – chucking a bunch of British tea into Boston Harbor – but what’s less often discussed is the impact on the textile industry. Led by American women, the Homespun and Non-Consumption Movements attempted a comprehensive embargo of British textiles in one of the earliest manifestations of the “Made in America” movement, then a tactic for evading colonial control. The Fashion Archive & Museum notes:

Cloth, like tea, also became politicized through the nonimportation agreements. Revolutionaries especially targeted silk and lace as symbols of luxury and status, specifically in the context of British imperial oppression and English extravagance. John Adams, in a letter to James Warren, wrote that “Silks and Velvets and Lace must be dispensed with [as] Trifles in a Contest for Liberty.” The Continental Association of 1774 declared that wool was the best republican material, because it was the furthest thing from the British extravagance of silk and lace. With the nonimportation agreements limiting the supply of cloth coming into the colonies, combined with the dislike of luxurious cloth, the colonists had to create their own cloth for practical and political reasons […] Spinning was one way that America could begin to manufacture for itself, or at least provision the colonists until Britain repealed the odious Townshend Acts. Spinning was a strictly female task, but because it held such political significance, it received a lot of attention, with one newspaper claiming that these women “determined the Condition of Men, by means of their Spinning Wheels: And Virgil intimates, that the Golden Age advanced slower, or faster, as they spun.”8

As you may remember, we discussed in Part One how the Intolerable Acts played a role in the history of Georgian moral sentiments toward the Americas – those Acts were passed due to American resistance to the Townshend Acts, and were of course one of the inciting forces of the American Revolution. After the Revolutionary War, Britain used a variety of methods to attempt to maintain its dominance and control over the United States, none the least of which were its attempts to monopolize the textile industry. Christopher Klein provides us with a delightfully dramatized account of how the United States broke through Britain’s vice grip on textiles manufacturing, writing:

The fledgling country, however, lacked a domestic textile manufacturing industry and lagged far behind Great Britain. The quickest way to close the technological gap between the United States and its former motherland was not to develop designs from scratch—but to steal them. In his 1791 “Report on Manufactures,” Hamilton advocated rewarding those bringing “improvements and secrets of extraordinary value” into the country. Among those who took great interest in Hamilton’s treatise was Thomas Attwood Digges, one of several American industrial spies who prowled the British Isles in the late 18th and early 19th centuries in search of not just cutting-edge technologies but skilled workers who could operate and maintain those machines. In order to protect its economic supremacy, the British government banned the export of textile machinery and the emigration of cotton, mohair and linen workers who operated them. A 1796 pamphlet printed in London warned of “agents hovering like birds of prey on the banks of the Thames, eager in their search for such artisans, mechanics, husbandmen and laborers, as are inclinable to direct their course to America.” 9

The geopolitical locality of these developments are very important. New England had been the earlier epicenter for revolutionary sentiments in the United States and the core focus of the British Intolerable Acts, and it would be New England and its neighbors that would see the first American textile mills developed after the technology was stolen from the British. Klein continues:

That’s what Samuel Slater did. The English-born cotton mill supervisor posed as a farmhand and sailed for the United States in 1789. Having memorized the details of Richard Arkwright’s patented spinning frames that he oversaw, Slater established the young country’s first water-powered textile mill in Rhode Island and became a rich man. While President Andrew Jackson dubbed him “Father of American Manufactures,” the English had a quite different nickname for him—“Slater the Traitor.”10

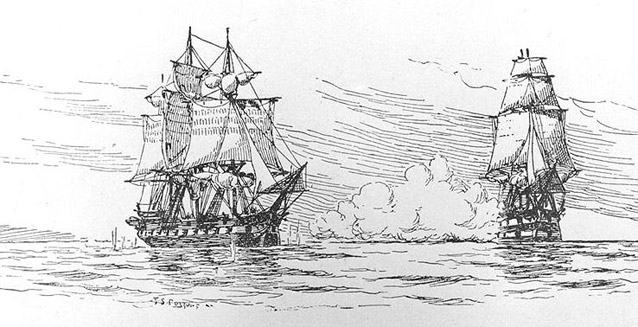

This is where the history in this article comes into direct proximity with the history of the Napoleonic Wars which we discussed in Part Two. Despite American attempts to grow the textiles industry, the United States was still heavily dependent upon British textiles. As we’ve already discussed, Britain and France both began heavily policing and encroaching upon maritime trade midway through the 00’s, leaving the United States crunched between the two superpowers as its sailors were repeatedly pressed into service by the British Navy. These British attempts came to a head in 1807 when a British naval vessel attacked an American vessel right off the coast of Virginia, impressed its sailors, and hung a man for “desertion.” This flagrant violation of America’s sovereignty (known as the Chesapeake Affair) infuriated the entire entire country and would eventually be one of the primary causes of the War of 1812, but led in the shorter term to the Embargo Act of 1807, which outlawed trade both in and out of America for about a year, including the lucrative international cotton trade:

Although the embargo was successful in preventing war, its negative consequences forced President Jefferson and Congress to consider repealing the measure. The American economy was suffering and American public opinion turned against the embargo. Moreover, goods continued to reach Great Britain through illegal shipments and British trade was not suffering as much as the framers of the embargo had intended. There was an initial effect on the price of goods in Britain, but the Britons quickly adapted to the altered prices, and supplemented their decreased North American trade with South American commerce. Items that could not be replaced through other trading partners were not goods that were vital to the survival of the country. The other country in question, France, almost seemed to welcome the American embargo because it supported Napoleon’s Continental System.13

Corbett, Janssen, et al. observe:

The Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 played a pivotal role in spurring industrial development in the United States. Jefferson’s embargo prevented American merchants from engaging in the Atlantic trade, severely cutting into their profits. The War of 1812 further compounded the financial woes of American merchants. The acute economic problems led some New England merchants, including Francis Cabot Lowell, to cast their gaze on manufacturing. Lowell had toured English mills during a stay in Great Britain. He returned to Massachusetts having memorized the designs for the advanced textile machines he had seen in his travels, especially the power loom, which replaced individual hand weavers. Lowell convinced other wealthy merchant families to invest in the creation of new mill towns. In 1813, Lowell and these wealthy investors, known as the Boston Associates, created the Boston Manufacturing Company. Together they raised $400,000 and, in 1814, established a textile mill in Waltham and a second one in the same town shortly thereafter.14

That group of incredibly wealthy Northern businessmen who had largely made their fortunes through textiles and other early industrial manufacturing ventures were deeply invested in the project of American manufacturing independence. The Boston Associates were an enormously influential presence in American politics during the first half of the 19th Century, and played no small part in developing the modern shape of American capitalism and the American economy. They were also largely Evangelicals, and their money and influence would be directly responsible for the creation of the American Whig Party.

Before we move on, though, I want to reflect on this unique impact of the American textiles industry upon the economic prerogatives of its time. What emerges is a tug of war between the Southern desire to export raw cotton to Britain and the Northern desire to increase the domestic production of textiles and outcompete the Motherland. But textile manufacturing was hardly an industry in isolation. One of the primary reasons for the creation of both railroads and steamboats in the early-1800s was the shipping of raw cotton from South to North to lower the costs of domestic textile production – one of the biggest early railways, Boston and Lowell, was both run and funded by members of the Boston Associates for the express purpose of transporting cotton between warehouses and factories. These mobile signs of industrialization grew a heavy association with the North, and became the site of intense politicking across the United States. In Part Four of this series, we’ll discuss how steamboats traveling North on the Mississippi River became one of the contested political transverses that foregrounded the first criminalization of American cross-dressing, so keep that economic connection in mind as we move forward into the political and social aspects.

The Second “Great Awakening”

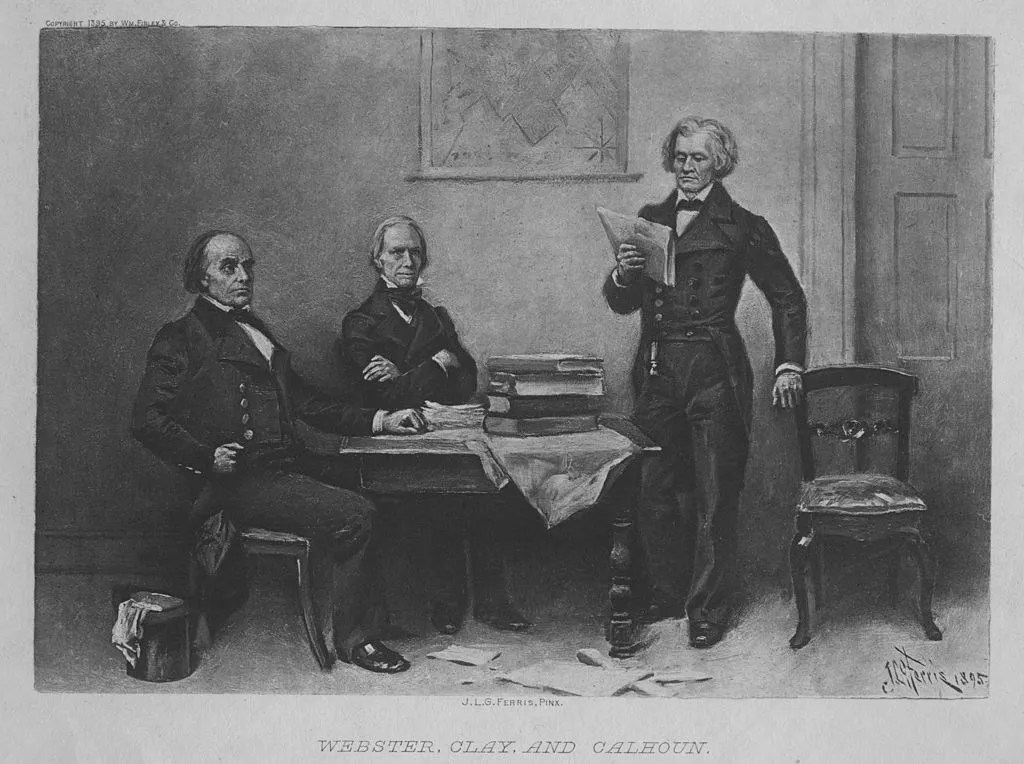

There are three politicians from this era, often called the “Great Triumvirate,” who are often cited as a useful barometer for the politics of the era. Two of them, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, were both profoundly Evangelical and would later go on to be Whigs. Henry Clay was a Kentucky politician and was often cited as a representative of the Western settlers, whereas Daniel Webster was a Massachussetts man through and through and represented Northern industrial interests. Understanding how Clay and Webster each represented a different facet of American Evangelicalism will help us understand the political imperatives of the Whig Party, and thus the social and political backdrop for the criminalization of cross-dressing in the 1840s.

Henry Clay’s political fortunes and the Second Great Awakening are extremely closely bound together, as both originated in Kentucky at around the same time. While it may have originated in “camp gatherings” where thousands of revelers flocked to the wilderness to have spiritual revelations, the Second Great Awakening quickly snowballed from isolated events in the mountains of Appalachia and the Midwest into a massive political movement with the power to move elections. On the emergence of the Evangelicals as a political force, Donald Scott writes:

Historians have usually looked to political parties, reform societies like temperance organizations, or fraternal associations like the Masons for the origins of this new associational order. In fact, evangelicals were its earliest and most energetic inventors. Indeed, as historian Donald Mathews has pointed out, the Second Great Awakening was an innovative and highly effective organizing process. Religious recruitment was intensely local, a species of grass-roots organizing designed to draw people into local congregations. But recruitment into a local Baptist, Methodist, or Universalist church also inducted people into a national organization and affiliational network that they could participate in wherever they moved. Moreover, adherence to a particular evangelical denomination also inducted them into the broader evangelical campaign. Conversion thus not only brought communicants into a new relationship to God, it also brought them into a new and powerful institutional fabric that provided them with personal discipline, a sense of fellowship, and channeled their benevolent obligations in appropriate directions. Aggressively exploiting a wide variety of new print media, evangelicals launched their own newspapers and periodicals and distributed millions of devotional and reform tracts. (By 1835, the cross-denominational American Tract Society and the American Sunday School Union alone distributed more than 75 million pages of religious material and were capable of delivering a new tract each month to every household in New York City.) They deployed home missionaries, circuit-riding preachers, and agents from town to town preaching revivals, organizing new churches and religious reform societies, and distributing Bibles and other religious materials. By the l830s, these devices, in conjunction with the aggressive revivalism that was the hallmark of the new evangelicalism, had assembled a huge new evangelical public. Not for nothing did evangelicals and nonevangelicals alike dub this new religious phalanx the “Evangelical Empire.”16

It absolutely needs to be noted that, as far as I can tell, most of the sources which discuss make no mention whatsoever of its corollary social trends in Britain, nor do they acknowledge that the term “Second Great Awakening” seems to be an American frame device to suggest a grand social progress to Evangelical history. Much of the information on the internet is pushed by Christian Evangelical interest groups, and thus I don’t consider it particularly reliable. Donald G. Matthers, who Scott cites in the prior article, describes it as such:

The Second Great Awakening is one of those happily vague generalizations which American historians use every now and again to describe a movement whose complexity eludes precision. […] To be able to say so much about the Awakening might be taken as evidence that it is not such a vague term after all. Yet there are too many unsettling things about the literature relating to it to conclude that present interpretations are sufficiently comprehensive. The difficulties are a mixture of too much emphasis upon the truly intricate and challenging intellectual problems of the New England theology, and a certain awesome impressionability in regard to the non-rational phenomena of revivalism in the burned-over districts of New York and Vermont, and the campmeeting grounds of the South and West. In fact, it is emotionalism and devout piety, heart over reason, commitment as opposed to disinterestedness which characterizes the revival for many scholars.17

He continues:

Certainly the Awakening had many of the attributes of a general movement. To be sure, it had less form than the later, more clearly defined reform, “nativist” and abolition movements, and its primary goals were certainly not consciously to effect a major change in the social structure. Furthermore, it was institutionalized in different “denominations” and in the end tended to be almost identical with the population in general. But these are not damaging admissions since the Awakening also had most of the requirements for a general social movement. In the first place it grew from a few converts to an expanding organization of Americans in small groups all over the country. Secondly, its expansion was in large part the work of a dedicated corps of charismatic leaders who proposed to change the moral character of America. Moreover, as the movement grew, a new corps of administrators “routinized” the charisma, created new institutional forms and standardized what once had been spontaneous. Before that happened, however, an ideology of personal “salvation” and moral responsibility had produced a sense of purpose and participation that divided the sheep from the goats-the ingroup from the out, the saved from the damned-and provided common standards for evaluating and enforcing behavior. There were other characteristics as well, unique to the time and situation of the movement; but whatever its peculiarities, it was more than a series of religious “crazes” and camp meetings. Mobilizing Americans in unprecedented numbers, it had the power to shape part of our history.18

While Henry Clay was not an Evangelist any more than Daniel Webster was a Boston Associate, he owed much to the movement that had elected him. Clay had been appointed in 1805 to teach law at Transylvania University (founded as Transylvania Seminary), the first institution of higher education west of the Appalachians, which both served as a blueprint for dozens of other Evangelical seminaries and universities across the Midwest. Clay had been educated by George Wythe, a Founding Father and a close friend of Thomas Jefferson, and in 1803, one of his first acts in Kentucky’s state legislature was to gerrymander the hell out of the electoral map to ensure that all of Kentucky’s delegates would go to Jefferson (Ironically, this happened almost a decade before the word “gerrymander” was even invented. Truly Clay was ahead of his time).

In Part Two of this series, we discussed how the British Whig Party – also predominantly composed of Evangelicals – broadly supported the colonization of Sierra Leone. Although the Whig Party would not rise to prominence until a few decades later, Henry Clay’s early career mirrors many of the British political trends concerning the moral amelioration of the slavery issue, and Kentucky was, of course, a slave state. Once again, the same dissonance that we observed in Jefferson’s rhetoric lays itself bare – Clay supported the gradual abolition of slavery, yet in 1804, he began a famous plantation in Lexington that would eventually enslave over 120 individuals. Knowing how deeply Clay had staked his career and self-image on Jefferson, it’s not hard to connect the dots there. When it concerned the Slavery Question, the moral imperative of the Western Evangelical had little to do with the full abolition of slavery and everything to do with the cleansing – the purging – of the Evangelical moral conscience. It should come as no surprise to us then that Clay was one of the primary founders of the American Colonization Society in 1816, which took up the British Colonization Movement and formed an American equivalent in the new colony of Liberia where slaves and free blacks could be forcibly deported to. But even this pales in comparison to the real legacy which Henry Clay left upon the issue of slavery: his 1820 negotiation of the infamous Missouri Compromise, and his role as the lead sponsor of the Compromise of 1850, which dealt with the Fugitive Slave Act, one of the most notorious pieces of pro-slavery legislation in American history.

Despite how vile those “accomplishments” on the issue of slavery may seem in retrospect, Clay built a reputation for himself as America’s “Great Compromiser.” For most of American history, he was remembered as one of the great champions of bipartisanship, which ignores the fact that his “compromises” almost always came in favor of Western expansion and with concessions to the slaveholding interest. Henry Clay represented the Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern planter class seeking to expand their interests West, a group whose Evangelical principles of freedom and abolition were fundamentally warped by their investment in the slave economy and who were willing to compromise for unity no matter the moral cost.

On the other hand, Daniel Webster represented a very different political investment in slavery: one not based upon an “awakening” of moral guilt (despite actively owning slaves) but rather the economic aims of a powerful textiles and manufacturing lobby whose money and patronage had both made him famous and put him in office. From the beginning of his career to its end, Webster’s fortunes were deeply tied up with the Boston Association and their business interests. Rising to prominence as a young lawyer, Webster represented several high-profile clients from the association, including Francis Cabot Lowell among others, and it was the Boston Association that would successfully fund his election bids in the 1820s. Remini writes:

Webster needed an understanding about his financial situation before he accepted the nomination. He had a very lucrative law practice that a congressional career would substantially reduce. If the elite of Boston wanted his services in Congress, it would have to pay for it. […] As a matter of fact, ever since his arrival in Boston he had personally benefited from the support of the business community. The Boston Associates had been particularly generous and on December 7, 1821, even allowed him to buy four shares, costing one thousand dollars apiece, in the Merrimack Manufacturing Company, “an association for the purpose of manufacturing and printing cotton.” This was a privilege granted to few others. It was a modest number of shares, to be sure, but it demonstrated the group’s confidence in him and his future and its readiness to provide for his financial needs. These Boston Associates became his financial patrons and were repeatedly invited to contribute to his campaigns with loans or outright gifts.19

Early capitalism at its finest.

We need to consider Webster’s political investments from two different angles. On one hand, there was a need to keep a continuous supply of cheap cotton from the South, and on the other, a need to provide cheap labor to produce textiles using that cotton at the lowest possible cost. This played out in a variety of ways over the course of Webster’s career. There’s a book that goes into much greater detail about the role of the Boston Associates in national politics that I unfortunately did not have access to while writing this article, but there are two issues that are of particular relevance here, and I’ll devote a short paragraph to each.

Firstly, Daniel Webster was the lead lawyer in arguing an obscure Supreme Court case that only lawyers pay attention to: the Gibbons vs. Ogden case of 1824, which made it illegal for a company to monopolize forms of transit within a state and forbade the states from interfering with national commerce agendas. The particular issue at stake here was, once again, the steamboat: New York had offered a steamboat monopoly to one company within their waters, and the Boston Associates had a vested stake in disrupting that to enable the cheaper transport of their goods up and down the Hudson River. But the impact of this decision went far beyond the steamboat industry. Alex McBride writes:

Gibbons v. Ogden set the stage for future expansion of congressional power over commercial activity and a vast range of other activities once thought to come within the jurisdiction of the states. After Gibbons, Congress had preemptive authority over the states to regulate any aspect of commerce crossing state lines. Thus, any state law regulating in-state commercial activities (e.g., workers’ minimum wages in an in-state factory) could potentially be overturned by Congress if that activity was somehow connected to interstate commerce (e.g., that factory’s goods were sold across state lines). Indeed, more than any other case, Ogden set the stage for the federal government’s overwhelming growth in power into the 20th century.20

The industry that stood to lose the most from this decision was, of course, slavery, or the “peculiar institution” as it was often called at the time. By expanding the power of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce, Gibbons vs. Ogden increased the future possibility of a federal ban on slaveholding activities – but also created the possibility for slave states to use the federal government to protect slaveholding commerce across state lines, particularly in cases where slaveholding property (i.e., fugitive slaves) might happen to cross those lines. Controlling the federal government had always been a primary concern for slave states, but the 1820s saw a serious consolidation of their attempts to calcify themselves within the federal government, perhaps best embodied by Andrew Jackson’s legacy (we’ll get to him).

On a different tack, we pose the question: if the Boston Associates weren’t using slave labor to produce their textiles, how did they acquire workers? Well, instead of exploiting Blacks, they just exploited women instead! The National Park Service writes:

The term “mill girls” was occasionally used in antebellum newspapers and periodicals to describe the young Yankee women, generally 15 – 30 years old, who worked in the large cotton factories. They were also called “female operatives.” Female textile workers often described themselves as mill girls, while affirming the virtue of their class and the dignity of their labor. During early labor protests, they asserted that they were “the daughters of freemen” whose rights could not be “trampled upon with impunity.” […] To find workers for their mills in early Lowell, the textile corporations recruited women from New England farms and villages. These “daughters of Yankee farmers” had few economic opportunities, and many were enticed by the prospect of monthly cash wages and room and board in a comfortable boardinghouse. Beginning in 1823, with the opening of Lowell’s first factory, large numbers of young women moved to the growing city. In the mills, female workers faced long hours of toil and often grueling working conditions. Yet many female textile workers saved money and gained a measure of economic independence. In addition, the city’s shops and religious institutions, along with its educational and recreational activities, offered an exciting social life that most women from small villages had never experienced. […] For most young women, Lowell’s social and economic opportunities existed within the limits imposed by the powerful textile corporations. Most pronounced was the control corporations exerted over the lives of their workers. The men who ran the corporations and managed the mills sought to regulate the moral conduct and social behavior of their workforce. Within the factory, overseers were responsible for maintaining work discipline and meeting production schedules. In the boardinghouses, the keepers enforced curfews and strict codes of conduct. Male and female workers were expected to observe the Sabbath, and temperance was strongly encouraged.21

There’s a lot to talk about here, but I’m only going to gesture at the two key points. The first point is that these were the social circumstances out of which most of the major progressive movements in the 19th Century emerged. Labor organizing, early feminism, many abolition movements can trace back to this emerging economic positionality of women in New England society during the early 1800s. Crucially, the temperance movement which sought and eventually accomplished the prohibition of alcohol would also emerge as a national political force thanks to New England industry and the monied interests behind it.

Second, it’s equally important, especially in the case of temperance, to identify why these powerful Bostonian businessmen were investing their moral and political fortunes in issues like temperance and reform, while balking at other causes like abolitionism and feminism. Underlying all of this, even the economic issues, was a core theological idea about the primary role of Evangelical Christianity in civil society. Much of the modern structure of capitalism can be elucidated through the ways that Northern economics adapted around the Northern moral compass. Slave labor was immoral, for example, but that didn’t change the economic prerogative for cheap labor. What emerges is the desire not only for cheap labor but moral labor, which was of course faithful labor, devout labor, labor which upheld the principles of the Evangelical movement. A pious laborer would be compensated first and foremost through her devotion to God and her admission into the Kingdom of Heaven. Hence why the Evangelical movement could simultaneously disavow slavery, advocate for temperance – an assurance that working women would not have their morals corrupted or perverted in the labor market – and pursue a virulent nativism that would persecute anyone and everyone who didn’t uphold that Evangelical mode of life. Protestant faith was not only prior to the economy – it was its foremost organizing principle.

So there is a tug of war in the first half of the 18th Century – a tug-of-war between Evangelicals who held faith over economy (as with the ardents of the Second Great Awakening) and those who held economy over faith. For the Boston Associates, Daniel Webster, and their ilk, they would largely fall into the latter category. Abolition, temperance, reform, women’s rights: all was tolerable until it began to bite into the factory’s bottom line. In the later years of the Whig Party, this divide would be clearly articulated into the “Conscience Whigs,” who believed so deeply in Evangelical principles that they did not care what impact it would have on industry, and the “Cotton Whigs,” who cared more about Northern business interests than the moral crusades of their time.

Henry Clay never cleanly fit into either camp, so concerned as he was for the preservation of the Union at any cost, but Daniel Webster was a Cotton Whig through and through. Clay might have sponsored the Compromise of 1850, but Webster was the one who got it passed. In his infamous “Seventh of March” address, he took a page from his own legal book from Gibbons vs. Ogden and made the following argument:

Mr. President, – I wish to speak to-day, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American, and a member of the Senate of the United States. […] It is said on the one side, that, although not the subject of any injunction or direct prohibition in the New Testament, slavery is a wrong; that it is founded merely in the right of the strongest; and that is an oppression, like unjust wars, like all those conflicts by which a powerful nation subjects a weaker to its will; and that, in its nature, whatever may be said of it in the modifications which have taken place, it is not according to the meek spirit of the Gospel. […] There are thousands of religious men, with consciences as tender as any of their brethren at the North, who do not see the unlawfulness of slavery; and there are more thousands, perhaps, that whatsoever they may think of it in its origin, and as a matter depending upon natural right, yet take things as they are, and, finding slavery to be an established relation of the society in which they live, can see no way in which, let their opinions on the abstract question be what they may, it is in the power of the present generation to relieve themselves from this relation. […] What right have they, in their legislative capacity or any other capacity, to endeavor to get round this Constitution, or to embarrass the free exercise of the rights secured by the Constitution to the persons whose slaves escape from them? None at all; none at all. Neither in the forum of conscience, nor before the face of the Constitution, are they, in my opinion, justified in such an attempt. […]

As has been said by the honorable member from South Carolina [Calhoun], these Abolition societies commenced their course of action in 1835. It is said, I do not know how true it may be, that they sent incendiary publications into the slave States; at any rate, they attempted to arouse, and did arouse, a very strong feeling; in other words, they created great agitation in the North against Southern slavery. Well, what was the result? The bonds of the slave were bound more firmly than before, their rivets were more strongly fastened. Public opinion, which in Virginia had begun to be exhibited against slavery, and was opening out for the discussion of the question, drew back and shut itself up in its castle. I wish to know whether any body in Virginia can now talk openly as Mr. Randoph, Governor [James] McDowell, and others talked in 1832 and sent their remarks to the press? We all know the fact, and we all know the cause; and every thing that these agitating people have done has been, not to enlarge, but to restrain, not to set free, but to bind faster the slave population of the South…22

We’ll talk more about 1835 in the next section, but before I even begin to explain to you how obscenity was criminalized in the United States, I want you to sit with the absurdity of Webster’s argument that the abolitionists were responsible for the moral failures of the South to free the slaves.

Yeah. Just sit with that for a minute.

By 1850, the power of the Boston Associates had waned, and this was the speech that lost Daniel Webster his seat in congress. But the damage had been firmly done. The Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act both would pass, and would lay the further foundation for the Dred Scott vs. Sanford decision of 1857 which would herald the coming of the Civil War. Ultimately for the Cotton Whigs, economic reliance upon the South for cheap cotton and other labor would outweigh the moral prerogatives of their Evangelical faith – and this would be early signs of a slow cancer that would pervert American Evangelicalism over the coming years from a force of progressive change and social justice into the bastion of conservative bigotry and ethno-fascist sentiment we find today.

The most important thing I need you to take away from this section is that even though Henry Clay and Daniel Webster represented very different sorts of American Whiggery, both of their shortcomings ultimately found their way back to the Slavery Question, specifically the issue of fugitive slaves. In truth, everything in the Antebellum Era terminated in the Slavery Question. By the end of the 1850s, American society had become so deeply wound around slaves, freemen, and their fugitive futures that it destroyed the Second Party System altogether. The Whig party would implode in resounding fashion in the early 1850s, and the rise of the decidedly more abolitionist Republican Party was such a system shock to the nation that it led the entire South to secede. But it is so important to recognize that while the Democrats may have written and voted for the bill, the Whigs were responsible for many of the most notorious pro-slavery laws of the 19th Century. Their utter failure to translate the moral convictions of their Evangelicalism into political gains for marginalized and enslaved peoples was a direct product of their economic investments in slavery, early capital, and Western expansion.

Millennialism, Nativism, and the Jacksonian Era

Webster and Clay may have represented two different facets of the American Whig Party, but neither of them are useful narrative loci for teaching a modern audience the history of the Whig Party and the Antebellum Period more broadly. So let me instead take on a case study who will help us to think through the social trends of the time and understand how all of this provided the grounds for the criminalization of cross-dressing and obscenity.

Our key figure to follow in this case study is one Lyman Beecher, an American Minister who was very famous and influential across a broad swathe of American culture at the time. Beecher also fathered several prominent figures, who numbered among them abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher and writer Harriet Beecher Stowe, who authored Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Nevertheless, the man was famous in his own right, and was directly involved in many of the social movements of the first half of the 19th Century, including but not limited to abolition, reform, and temperance, i.e., all of the hot-button Evangelical issues of his time.

I want us to read the life of Lyman Beecher against that of William Wilberforce which we discussed in Parts One and Two. While Beecher was a preacher and Wilberforce was a politician, each man was enormously well-respected in Evangelical circles during their times, and seen as a moral leader by many of their peers. They both held massive influence, and both were seen as progressive figures in their time. Moreover, we have evidence that Lyman Beecher took direct influence and inspiration from Wilberforcean moral crusades for his own work, shown not in the slightest by his creation of the “Connecticut Society for the Suppression of Vice and the Promotion of Good Morals.” Around the start of the 1810s, the American Temperance movement would be beginning to find its first legs. Of the early phase of Beecher’s career, scholar Jeremy Land writes:

Dr. Lyman Beecher quickly became known for his fiery sermons and his unapologetic hatred for intemperance. He was the minister of the East Hampton Presbyterian Church until 1810 when he moved to Litchfield, Connecticut where he began to pursue the ultimate goal of his theology: the suppression of all sin throughout the nation. He felt that only through the unity of religion would unity of the nation be fully achieved. Around 1813, after years of preaching that sin would destroy the republic, he founded the Connecticut Society for the Suppression of Vice and the Promotion of Good Morals. The name of the society conspicuously advertised its major goal: a Connecticut and an America free of sin and a shining example of morals for the world. […] One of the very first tracts he would print was his sermon on using societies to suppress sin called, The Practicality of Suppressing Vice by Means of Societies Instituted for that Purpose. He quickly won fame for his efforts with the Connecticut society. Although the results of his first tract war were discouraging, he remarked in his autobiography, that “by voluntary efforts, societies, missions, and revivals, (ministers) exert a deeper influence than ever they could by queues, and shoe-buckles, and cocked hats, and gold-headed canes.” He still felt that ministers could establish societies that would ultimately change American morals to reflect the ideals he felt were necessary to fulfill his goals.24

This should be starting to sound very familiar at this point. But even though the trappings of the endeavor resembled Wilberforce’s various efforts in a number of ways, even from the beginning Beecher’s work was marred and held back by a sharp anxiety over the future and character of his country. Aaron and Musto write:

Lyman Beecher, who in 1812 organized other leading churchmen and established the Connecticut Society for the Promotion of Good Morals, was an avowed conservative determined “to save the state from innovation and democracy. Our institutions, both civil and religious,” he wrote, “have outlived that domestic discipline and official vigilance in magistrates which rendered obedience easy and habitual. The laws are now beginning to operate extensively upon necks unaccustomed to the yoke, and when they become irksome to the majority, their execution will become impracticable. To this situation we are already reduced in some districts of the land. Drunkards reel through the streets day after day, and year after year, with entire impunity. The mass is changing. We are becoming a different people” (Krout 1925, p. 86). Clearly, the significance that Beecher and others of his class attached to drunkenness cannot be separated from their anticipation of the downfall of the standing order. Personal insobriety was feared because it was a harbinger of social chaos. Despite Beecher’s admitted antidemocratic sentiments, his perception that drunkenness was more common and more overt in its display was shared by a wide spectrum of Americans. The meaning of this phenomenon may have been interpreted differently, but what people observed seemed to be the same thing.25

These anti-democratic sentiments echo Baron John Campbell (see Part Two) and his desire to expand the right to vote only insofar as it applied to inequities within the landed British aristocracy. But unlike in the United Kingdom, where anti-vice ideals and abolitionism had been linked together as a marker of national pride, unity, honor, and moral restoration, the United States faced a landscape where those same issues were actively tearing it apart. In the view of the Slavery Question, this certainty of impending doom without significant moral upheaval reveals itself not just as a racial anxiety, deeply invested with the trappings of guilt, but also with a broader social idea in the Second Great Awakening movement known as Millennialism. Matthew Avery Sutton writes:

One prominent manifestation of Second Great Awakening millennial hope emerged in the work of the many new benevolent societies of the 1810s and 1820s, such as the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions and the American Tract Society. God, members of these benevolent groups insisted, was not a wrathful, vengeful deity waiting to destroy the earth, but a gracious, benevolent father working to bring the whole world to salvation. As the historian James Moorhead explains, much of the cultural power of postmillennialism in the early republic drew on cataclysmic images of the end times and then turned that energy toward the making of an evangelical empire. Millennialism also helped shape parts of the abolitionist crusade, another significant reform movement in antebellum America. Many leading abolitionists believed that as the kingdom neared, individual humans would free themselves from sin. They also believed that they needed to purge society of its sins, and none was more significant than the sin of slavery. Theirs was not, however, a popular or even mainstream position. Their application of millennial theology to the slavery question created many more enemies—even among fellow Christians—than friends.26

Beecher would later be involved in the American Tract Society, along with the American Bible Association, the American Society for the Promotion of Temperance, and several other organizations. What I want to interrogate about his career, however, is his complicated relationship with abolitionism, which was tortured in part because of the imperial and nativist elements of his millennialism. Though critical, Land takes an overall positive tone on Beecher’s engagement with the movement in this stage of his career, writing:

Lyman Beecher was beginning to realize just how volatile the slavery issue was in American life before 1830, but he attempted to avoid the issue by focusing on the alcoholism that he perceived to afflict the entire nation. Yet, his feelings on slavery would be incorporated into his sermons. He quickly became known for his fervor and spirit in fighting intemperance because his sermons on the subject were printed and distributed throughout the nation. The most famous of them all were actually a set of sermons bound together called “Six Sermons on the Nature, Occasions, Signs, Evils, and Remedy of Intemperance.” In these sermons, he attempted to equate slavery with intemperance.27

Land seems to hold that even though Beecher was wishy-washy on the issue of abolition at best, his liberalism on the matter still makes him one of the more important figures in the history of the movement. I would rather argue that Beecher’s inability to commit himself fully to the issue of abolition is a symptom of the problems with the American Whig and American Evangelicalism more broadly, alienating the voters who took object with his abolitionist leanings without truly using his platform to express the necessity of the endeavor.

In 1820, the United States, led by the work of Henry Clay, would pass the Missouri Compromise, which admitted Missouri to the Union as a slave state, Maine as a free state, and drew a dividing line across the 36th Parallel that would be the future boundary between all future Northern free states and Southern slave states. At approximately the same time, the Panic of 1819, America’s first financial recession, would shake the nation’s economy (after Europe recovered its agricultural sector following the 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora). Among the many wide-ranging consequences of the recession, one complete accident was that it would lead to one the nation’s most famous young war heroes, Andrew Jackson, losing his job as a general.

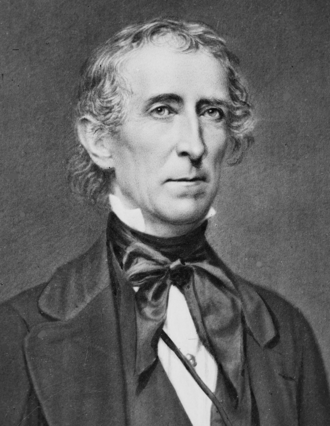

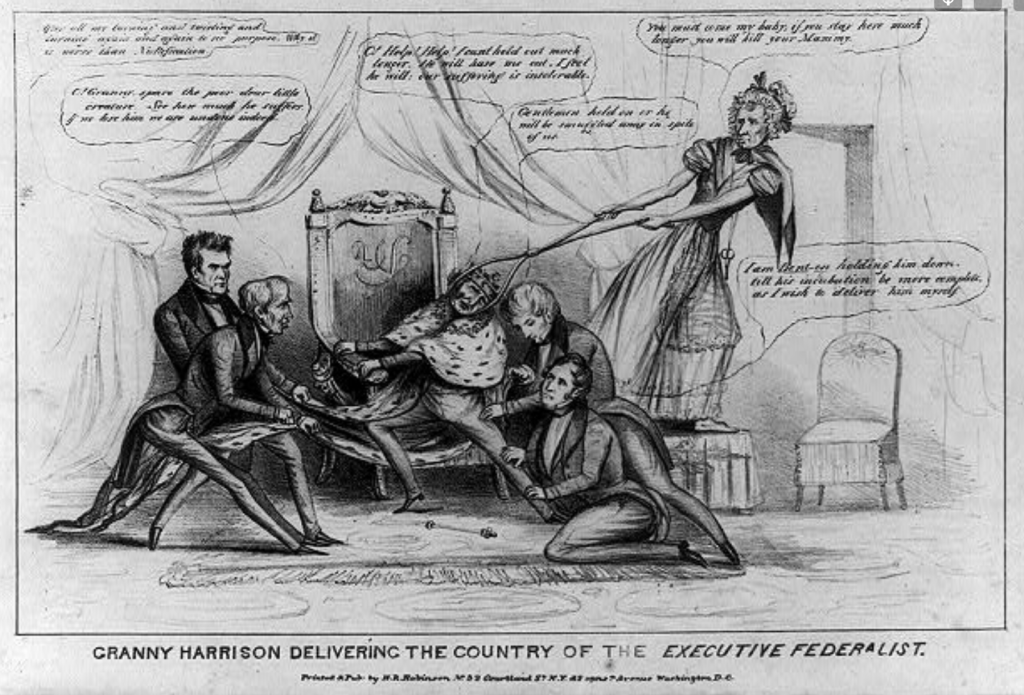

Andrew Jackson was a slave-owner, the primary architect of the Indian Removal Act, the overseer of the Trail of Tears, and the only president to ever fully pay off the national debt. His immense economic popularity was rivaled only by his rabid taste for expansionism. He had risen to fame at the end of the War of 1812 for his victory over the British during the final Battle of New Orleans, where he also garnered himself a negative local reputation for his brutal martial law during the occupation of the city; he then went on to lead the American army in war against the Seminole people over the next few years, leading to the dislocation of the tribe from their lands. Jackson was so popular that the political party which ran against his Democratic party in his re-election campaign was colloquially known as the “Anti-Jackson Party.” That ramshackle party would then proceed to lose to such a resounding degree that it sealed the end of any contemporary form of political opposition, and led to the birth and rise of the American Whig Party in its stead.

Now contemporary progressive critics have picked Jackson to death, so I won’t go into too much detail. The most important thing to know is that Jackson represented the death of early American federalism, and a sharp populist turn against big government as a regulating force in American society. Andrew Jackson ran against John Quincy Adams in 1824 in what would become the second contingent election in American history – in other words, even though Andrew Jackson won both the electoral college and the popular vote, his failure to achieve a 50% majority of the Electoral College threw the decision to the House, who elected John Quincy Adams instead. This moment in American history is known as the “Corrupt Bargain,” and it stands to this day as a testament to how profoundly the Electoral College system does not work in a thriving democracy.

To say that the Election of 1824 had a significant impact on American history is an understatement. Incensed by their belief that the Presidency had been stolen from Jackson (and you’ll remember that Gibbons vs. Ogden expanded the commercial powers of the federal government in the same year), a massive populist movement rose to elect Jackson as a two-term President. The Election of 1832 was one of the biggest landslides in American history, which tells you a lot about just how well-liked Jackson was. He was so popular and successful, in fact, that in 1832, Henry Clay was the Presidential nominee for the National Republican Party, often better known as the “Anti-Jacksonian Party.” That coalition promptly collapsed after their total failure to combat Jackson, and the American Whig Party was born as the next attempt to unseat the Democrats in its wake.

What separated the Whigs from the National Republicans? Unlike their prior incarnation, the Whigs did have a distinct political identity of their own: they were Evangelicals. Daniel Walker Howe writes of this Sectarian division within the Democrat-Whig system:

The supporters and opponents of the evangelical revival constituted the two largest of all the mutually hostile moral communities or reference groups identified by the ethnoreligious interpretation. The multiplicity of religious bodies sorted themselves out into two camps, prorevival and antirevival, that then meshed with the two-party political system. By the time of the classic Whig-Democratic confrontation in 1840, the evangelicals were openly and actively enlisted in the Whig campaign, their opponents arrayed on the Democratic side. There is some reason to think that evangelical opinion leaders (like their counterparts on the opposite side) were more strongly partisan than their followers. If so, then the degree of involvement with the evangelical cause would correlate with the degree of support for the Whig party.28

Now, a modern audience may not know that the Whig Party even existed, much less that they forwarded four of America’s presidents, only two of whom were even elected, as both died in office. But between 1833 and 1856, the United States had more or less a two-party system called the Second Party System between the Democrats, who were more conservative and pro-slavery, and the Whigs, who were broadly more liberal. This American Whig Party was broadly inspired by the British political party of the same name; John Campbell, the architect of the Obscene Publications Act of 1857 we discussed in Part Two, was also a Whig. The American and British Whigs shared a mutual disdain for a strong authoritarian figureheads of state like Andrew Jackson – but the American Whigs were even less praiseworthy on the issue of slavery than their British cousins. In order to win elections in the US, the Whigs had to appeal at least on some level to Southern voters, which meant that rhetoric around abolition needed to be significantly toned down in order to win on the national stage.

Like Clay and many other prominent Whigs at the time, Beecher was involved in the efforts of the Colonization Movement as a potential moral solution to the Slavery Question. An 1834 speech lays bare how many in the movement did not see Colonization as an abolitionist activity:

Our free institutions, public sentiment, the climate, and the depreciation of slave labor in some states,—in others, the exhaustion of the soil, and in all, the growing knowledge, impatience, inutility and peril of the slave population—the increase of emigration, from considerations of conscience or fear or necessity, and the existing or fast approaching emancipation of the colored race in the islands, in Mexico, and in many of the non-slaveholding states, all declare the termination of the relations of master and slave to be near. But as all past great changes in society have been accomplished by providential instrumentality, It is time that the chosen instrumentality should begin to be developed; and it is developed, in the extended and extending associations of the colonization and abolition societies, which, though like opposing clouds they seem to be rushing into collision, will, I doubt not, pour out their concentrated treasure in one broad stream of benevolence—like rivers, which ripple and chafe in their first conjunction, but soon run down their angry waves, and mingle their party-colored waters, as they roll onward toward the ocean. […] It will be my object to show, that in meliorating the condition of the colored race, there is a work for the Colonization society to perform, and that, in its proper sphere, it is worthy of continued confidence and efficient support, and that for the emancipation and elevation of the colored race, there is also a work which more properly belongs to a society for the purposes of Abolition, which, judiciously conducted, may win the hearty co-operation of all patriots and Christians.29

To be very clear, what Lyman Beecher is suggesting here is that the work of “meliorating” – ameliorating, making better – the condition of the enslaved person is an endeavor whose instrumentality can be separated from the “emancipation and elevation” of the enslaved person. This particular act of moral betterment is, further, carried out through the act of removing people of color from the United States and returning them back to Africa where they “belong.” I would be remiss not to point out that this Evangelical project of using British and American Blacks to colonize the coast of West Africa in not in the slightest dissimilar from the project of using Eastern European Jews to recolonize Israel – both acts stem from the fundamental root of millennialism, the belief that the sins of the Evangelical people must be purged in preparation for the apocalypse and the second coming of Jesus Christ.

This was hardly the only sidequest moral crusade that Beecher was occupying himself with during this period instead of taking an active stand for the abolition of slavery. He also was quite notoriously nativist, believed that the Catholic Church was going to destroy America, and took up a position at the Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, Ohio to pursue what he saw as his highest moral calling in life – proselytizing the Evangelical faith to the American West. His 1835 nativist screen “A Plea for the West” is one of the more dubious documents in American literary history, and he infamously incited a riot that resulted in the destruction of a Catholic convent. In “A Plea for the West,” Beecher gives us an even clearer picture of his incrementalism and his belief that by promoting the Evangelical faith, social progress must surely be inevitable:

No people ever did, in the first generation, fell the forest, and construct the roads, and rear the dwellings and public edifices, and provide the competent supply of schools and literary institutions. […] But the population of the great West is not so, but is assembled from all the states of the Union, and from all the nations of Europe, and is rushing in like the waters of the flood, demanding for its moral preservation the immediate and universal action of those institutions which discipline the mind, and arm the conscience and the heart. And so various are the opinions and habits, and so recent and imperfect is the acquaintance, and so sparse are the settlements of the West, that no homogeneous public sentiment can be formed to legislate immediately into being the requisite institutions. And yet they are all needed immediately, in their utmost perfection and power. A nation is being ” born in a day,” and all the nurture of schools and literary institutions is needed, constantly and universally, to rear it up to a glorious and unperverted manhood. […] Who then, shall co-operate with our brethren of the West, for the consummation of this work so auspiciously begun? Shall the South be invoked? The South have difficulties of their own to encounter, and cannot do it ; and the middle states have too much of the same Work yet to do, to volunteer their aid abroad. Whence, then, shall the aid come, but from those portions of the Union where the work of rearing these institutions has been most nearly accomplished, and their blessings most eminently enjoyed30

The “difficulty” of the South is slavery. It’s quite clear, given how similar that the language of “rushing” tides of history is between Beecher’s speeches about the Evangelism of the West and the colonization of Liberia, that the two endeavors were intrinsically linked in the man’s mind. The South’s ardent commitment to the Slavery Question is brushed off in this mode of 19th Century American Whig thinking as something to be carefully mitigated with institutions, a difficulty that will surely resolve itself through the Manifest Destiny of America and her mandate to Christ. Lest you doubt the moral and political compunctions of this text, let me give you Beecher’s account of all the history we have discussed up to this point, particularly in regards to how he frames the Evangelical impulse against Haudenosaunee (see Part Two):

There have been those, too, who have thought it neither meddlesome nor persecution to investigate the facts in the case, and scan the republican tendencies of the Calvanistic system. Though it has always been on the side of liberty in its struggles against arbitrary power; though, through the puritans, it breathed into the British constitution its most invaluable principles, and laid the foundations of the republican institutions of our nation, and felled the forests, and fought the colonial battles with Canadian Indians and French Catholics, when often our destiny balanced on a pivot and hung upon a hair; and though it wept, and prayed, and fasted, and fought, and suffered through the revolutionary struggle, when there was almost no other creed but the Calvanistic in the land ; still it is the opinion of many, that its well-doings of the past should not invest the system with implicit confidence, or supersede the scrutiny of its republican tendencies. They do not think themselves required to let Calvinists alone; and why should they ? We do not ask to be let alone, nor cry persecution when our creed or conduct is analyzed. We are not annoyed by scrutiny ; we seek no concealment. We court investigation of our past history, and of all the tendencies of the doctrines and doings of the friends of the Reformation ; and why should the Catholic religion be exempted from scrutiny ? Has it disclosed more vigorous republican tendencies ? Has it done more to enlighten the intellect, to purify the morals, and sanctify the hearts of men, and fit them for self-government? Has it fought more frequently or successfully the battles of liberty against despotism ? or done more to enlighten the intellect, purify the morals, and sanctify the heart of the world, and prepare it for universal liberty?31

This marvelous little piece of what-about-ism is also a great example of how the Indian signifier begins to become the symbol of any ‘foreign’ group in Nativist thought at the time.

What is not made readily apparent by this description of Beecher’s Evangelical activities was his failure to make any meaningful commitment to a concurrent abolitionist society that was blossoming while he was yapping about Liberia and the Catholics: the American Anti-Slavery Society, which several of his children participated in, and of which Wilberforce would certainly have approved. Consider what this 1953 article in The Liberator, the preeminent newspaper of the abolition movement run by William Lloyd Garrison, who also founded the AA-SS, had to say about the colonization movement:

Resolved, that our abhorrence of the scheme of African Colonization is not, in the slightest degree, abated; that we recognize in it the most intense hatred of the colored race, clad in the garb of pretended philanthropy; and that we regard the revival of Colonization Societies in various sections of the Union, and the explulsion of colored citizens from Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, and, more recently, from Illinois, as kindred manifestations of a passion fit only for demons to indulge in.32

The American Anti-Slavery Association was founded in the same year that the British abolished slavery (1833) by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan, two years after Nat Turner’s Rebellion (and Andrew Jackson’s swift destruction thereof) shook the nation. Frederick Douglas was heavily involved in the organization, and often spoke at its meetings, as were many of Beecher’s children. Of its founding, Henry Wilson wrote in 1872:

In the autumn of 1833 Evan Lewis, a member of the Society of Friends, conductor of “The Friend,” an antislavery journal in Philadelphia, and a man of whom it was said “he was afraid of nothing but being or doing wrong,” visited the city of New York to persuade leading Abolitionists to unite in calling a national convention. A small meeting was held, at which, after considerable discussion, it was voted, by a mere majority, to call such a convention at Philadelphia, on the 4th of the following December. Many Abolitionists, however, entertained serious doubts whether the time had come for holding a convention for that purpose. Nor is it a matter of surprise that such should have been the fact. It required principle, nerve; moral courage, and a martyr spirit thus to lead the forlorn hope of a then most unpopular cause; more even than when, under the cover of comparative obscurity, the New England society was organized. It was a time, too, of feverish excitement, exasperation, -and intense bitterness of feeling, word, and act; when the mob violence of the street was but the counterpart of the similar though more decorous demonstrations of the counting-room, the parlor, and the church. The Colonizationists had always manifested hostility to the antislavery cause. Their society had declared in 1828, four years before the organization of the New England Antislavery Society, that “it is in no wise allied to any abolition society in America or elsewhere; and is ready, when there is need, to pass a censure upon such societies in America.” The organization of societies pledged to immediate emancipation, the successful visit of Mr. Garrison to England, his unaccepted challenge of their champion to public discussion, the protest of Wilberforce and his compeers against their scheme, had so incensed its friends that even professedly Christian men were prepared to justify a resort to almost any measure to oppose and put down what they deemed a pestilent heresy. To go to Philadelphia at such a time and on such an errand was anything but a holiday affair.33

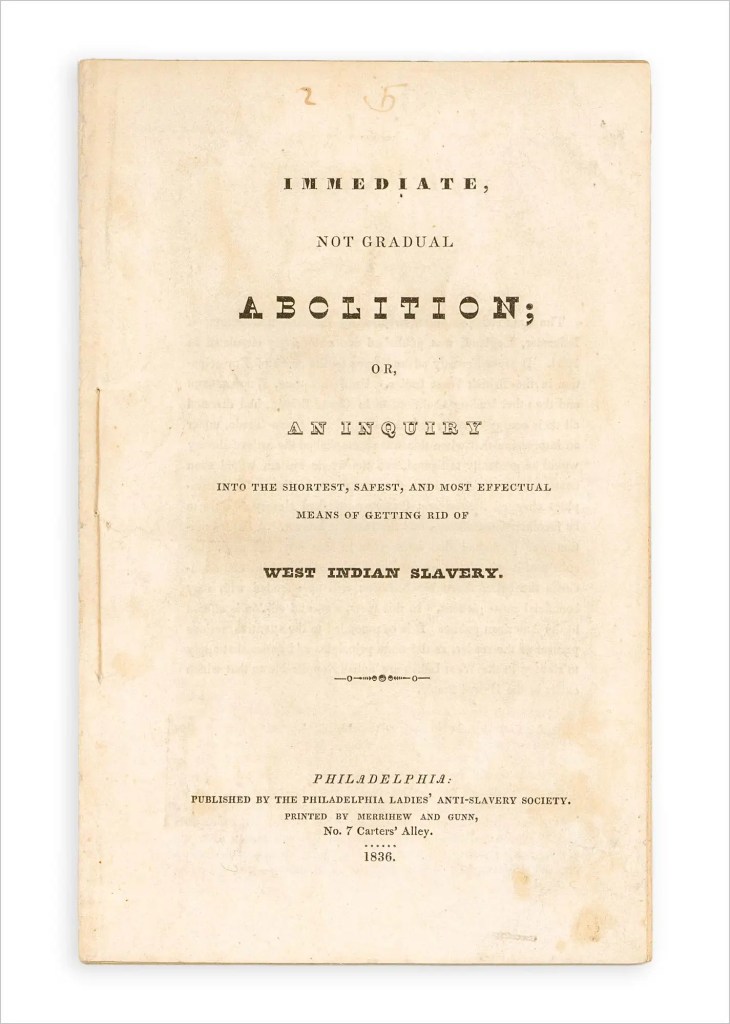

Beecher’s kids may have been inspired by his work, but Lyman Beecher himself, like many of the prominent Whigs of his generation, was no abolitionist. The anti-slavery organizing of the American Whig party was a pale shade of the work done by Wilberforce and his British allies. The AA-SS, on the other hand, was directly inspired by Elizabeth Heyrick’s call for immediatism, and her pamphlet “Immediate, Not Gradual, Abolition,” which we mentioned in Part Two, was reprefaced in America with the assertion: