- Homework for White People

- What Won’t Be Televised

- Whose Springtime?

- White Hegemony in Publishing

- Unthinking a Transliterary Blackness

- Your 2025 Black Transfemme Reading List (and Beyond)

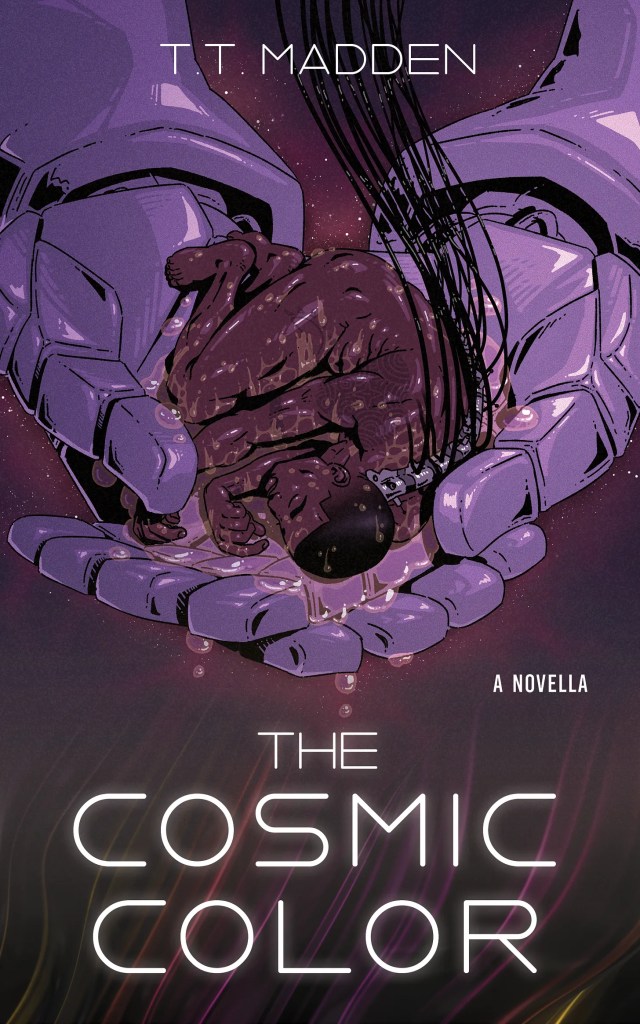

- The Cosmic Color by T.T. Madden

- Cabin Fever by Jack Harbon

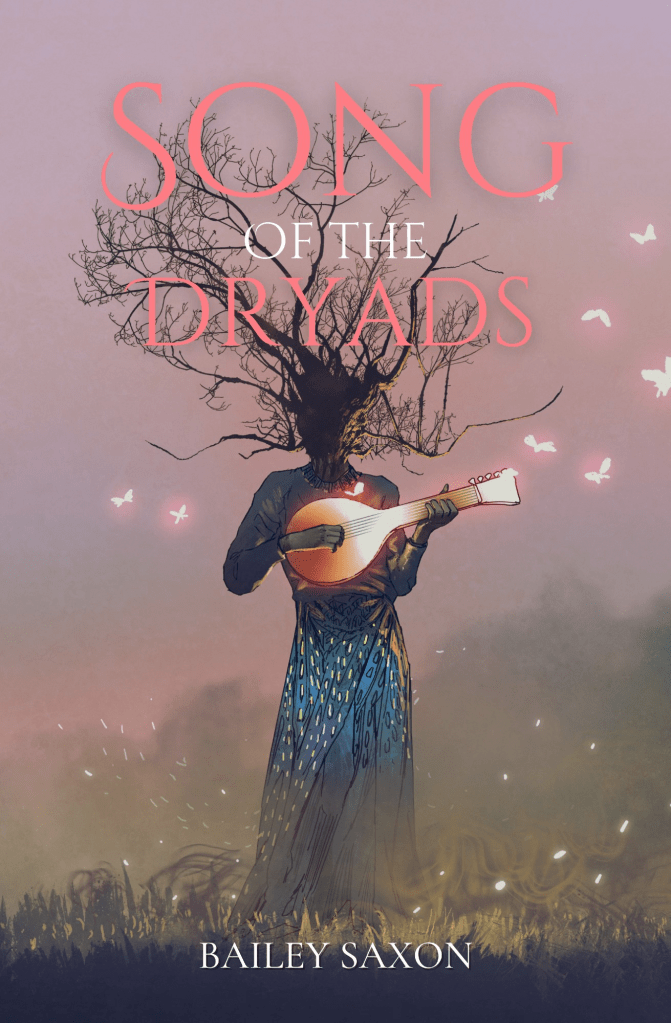

- Song of the Dryads by Bailey Saxon

- When the Harvest Comes by Denne Michele Norris

- One Day in June by Tourmaline

- Gorman’s House by T.T. Madden

- The Comfort of the Knife by Malaika Kirkwood

- The Neon Revelation by T.T. Madden

- She of the Fallen Stars by Dane Figueroa Edidi

- Collected Psalms by Dane Figueroa Edidi

- A Note from Our Sponsors!

Before we begin – The Transfeminine Review is now on Patreon! If you want to help us continue to produce vigorous public scholarship like this, please consider supporting us there.

This article was made possible by our Sponsors ❤

Homework for White People

Here’s an uncomfortable truth that we don’t talk about nearly enough – trans publishing can be incredibly white.

Systemic injustice always affect the most marginalized within its purview. There’s a long history of anti-trans discrimination in the publishing industry, yes, but that has always fallen most stringently upon racialized and transfeminized people of color. It’s hard to find a black or indigenous transfeminine character already, but an author? Unless you know exactly what you’re looking for, it can be like staring up at the hwhitest of clouds.

It’s Black History Month, which means that right now is a better time than ever for white trans folks to set some time aside to learn about the racial history of transness, and why it’s no historical accident that finding black trans authors, especially transfemmes, can be such a challenge. I’ve written about this a little bit in my A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature series, touching upon enslaved and colonial histories as they moved through the early roots of transvestite publishing. A couple other great places to start:

- If you haven’t read it yet, this would be a great moment to get around to reading Essays Against Publishing by Jamie Berrout. Berrout lays out the presence of white supremacy in trans publishing far more succinctly and directly than I can in this short article. It’s a lightning rod of a text.

- The seminal text on this issue is Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity by C. Riley Snorton – it’s written in an academic mode, but you’ll walk away from it with a really vigorous sense of the broad shape of the issue and many of the most fascinating historical examples that have helped modern trans theorists unlock the historical archive.

- If Black on Both Sides feels too inaccessible, then I would also recommend Snorton and Jim Haritaworn’s article “Trans Necropolitics,” which articulates and synergizes with many of the core points of the first two texts I’ve listed.

- For a broader introduction into Blaqueer feminist thought, I would recommend starting with Cathy J. Cohen’s classic article “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?”

- Want to hear about the history of radical Black trans activism straight from the people who pioneered it? You can check out Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonist Struggle, which collects a variety of the writings and interviews of Sylvia Rivera and Martha P. Johnson.

- If you want to understand where the Black trans liberation movement is today, there are two recent memoirs that I would highly recommend: Miss Major Speaks: Conversations with a Black Trans Revolutionary by Miss Major and Toshio Meronek, and The Risk It Takes to Bloom: On Life and Liberation by Raquel Willis.

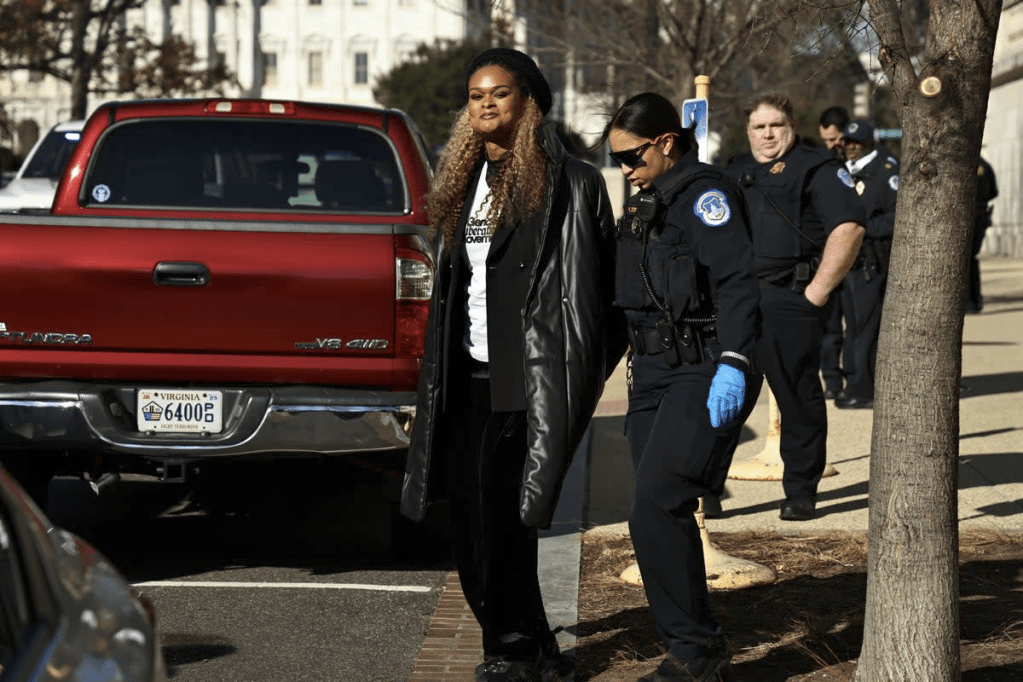

- Don’t stop at memoirs – you can donate right now to Raquel’s organization Gender Liberation Movement, which is doing some of the most critical work right now to oppose the current wave of anti-trans violence and discrimination in the United States. Unfortunately, Miss Major is currently sick, so if you want to perform some direct aid, you can donate to recovery efforts here.

It goes without saying, of course, that the biggest headline in the States right now is the drastic rollback of Civil Rights-era protections for Black Americans and recent gains for transgender Americans alike. It’s a dark moment in our political history – Black History Month observances are getting scrubbed from the program, vast swathes of federal data are getting censored and destroyed, and the negative impacts of these “anti-DEI” changes will be disproportionately felt by underprivileged black trans folks, as they always are.

Now more than ever, the trans community needs to rise to the moment and observe the histories and struggles of Black and Brown communities both in the United States and around the world. In their attempt to erase Black history, the Trump administration only underscores why now more than ever is a critical moment to support Black trans activism, Black trans storytelling, and Black trans art.

What Won’t Be Televised

I’ve been grappling for a few weeks now with how to approach an ‘anticipated releases’ post for the year. I knew I wanted to make one, but nothing felt right, so January came and went without one.

2025 is gonna be a banner year for trans literature – it’s already been observed in this essay from McKenzie Wark, which I won’t recant yet. My main takeaway from “Trans Fem Literary Springtime” was very similar to McKenzie’s: there are simply more books by transfemmes coming out right now than any one person can hope to document alone.

But that also begs the question – what gets documented, and what does not?

A few months ago, I published an article entitled “15 Black Transfeminine Novelists You Should Read Right Now,” which went somewhat viral by my standards at the time, in no small part because of its novelty. What that article taught me and many others was that many people had not only never read a black trans author, but had never even heard of one. A few people outright told me they hadn’t believed any existed.

It’s not hard to understand why. Many of those authors are extremely obscure, tucked away in corners of niche marketplaces, poorly advertised and little understood. In short – they were not documented.

Jamie Berrout has written a little bit about this siloed nature of trans of color authors and their ephemeral presence within the literary record. In her review of Lady Dane Figueroa Edidi’s post-modern magnum opus Yemaya’s Daughters, which is, for the record, still the only substantive piece of literary engagement with the text I have ever seen (please write literary criticism of Yemaya’s Daughters. I will publish it and pay you), Berrout wrote the following:

So much of what I do now is guided by the belief that even if I was doing work that was more innovative and well-crafted than anyone else it wouldn’t matter and it wouldn’t help me live in any real or material way. That it’s not just a waste of time to be focusing on revisions and (other people’s ideas of) language and gaining favor from those who control publishing – it actually causes harm because it demands I fit criteria that were made with other, very different people in mind. I’m a trans woman of color and that itself removes me from the world of literature – nothing I make can be published unless I contort or hide myself. And, as a result, I know that I need to find other ways to evaluate my writing and that of other trans women of color. Which brings me to the challenge of reading Dane Figueroa Edidi’s Yemaya’s Daughters, a novel that boldly creates its own world overseen by black women, cis and trans, set largely in an African Eden, and proceeds according to its own criteria of what is the ideal subject, language, and structure. A novel that seems to love and accept its own excesses and imperfections – to be clear, I wish that I could say the same about my own writing.2

Yemaya’s Daughters is a singular novel because of its nonlinearity – it is historical fiction without time, it is temporal fiction without history. The presence of Black trans life and the record of Black trans life cannot easily coexist under the auspices of white supremacy.

I wanted to help document Black trans literature in my last article, yes, but the most important thing that my October reading list did was developing a chronology of Black trans fiction as a literary motion. My thesis – and I believe it now more than ever – was that however submerged, the work and impact of working Black trans authors has had an indelible and often hard-to-trace influence upon the genre of trans literature as a whole. The trailblazing contributions of authors like Roberta Angela Dee, Pamela Hayes, and Dane Figueroa Edidi goes unmentioned in our historical conversations far too often – and if such a thing as “Black transfeminine literature” exists, it’s far from the minds of most who happen to stumble on a lone text.

Here’s a fact – 2025 is the best year for Black transfeminine literature, ever. Right now, there are more Black transfeminine novelists writing, publishing, and succeeding than at any point in history – but their presence is diffracted, diffused within the normative lenses of white supremacist publishing. There are no critics to give it narrative, no springtime, no fall. It is a history only written upon death.

In the days both leading up to and following the publication of my last article on Black trans lit, I was approached by several novelists featured in the article who told me that they had felt isolated, to varying degrees, from their Black transfemme peers in the publishing industry. Authorship is a solitary career, but there is a difference between solitude and isolation, between difference and separation. What I heard expressed – both by living authors and novels past, was that Black authorship in general, and Black transfeminine authorship in particular, are far too often a phantasmagoria of the latter.

It’s not transfemme-authored, but one queer novel that’s left a lasting impact on me is Real Life by Brandon Taylor, which follows a Black grad student at an elite research university in the Midwest through his suspended experiences of alienation and societal trauma. Wallace is neurotic, almost jittery on the page. He gets repeatedly stuck in impossible situations and can’t find his way out. Shola von Reinhold’s LOTE follows a very different protagonist in a very different academic setting, but many of the same antagonisms that constrain Wallace’s selfhood and ambition are limiting factors for Mathilda too. There is a certain monomania to Mathilda’s obsession with the cult of the lotus eater, the fatalism of a woman doomed – and I won’t spoil the end, but if you’ve read it, you may know what I mean. Mathilda flouts rules, Brandon espouses them – the recursion twists the same. Academia – White Academia – becomes a fulfillment of its own prophecy. A similar message in Alexandrine Ogundimu’s novel The Longest Summer: but it’s not academia, it’s the faux-marble halls of the suburban shopping mall. A lone Blaqueer protagonist, trapped within a banal and disorienting paradigm they cannot hope to escape.

White supremacy in publishing, much like the ideological state apparatuses of the academy and the mall, mandates that to be an “author” or “reader” (a “person”) is to be white by default. A list of “authors,” then, is a list of white authors, some of whom may happen to be people of color. To set out to create a list of “white authors,” then, is an absurdity; a semantic repetition; it need not be said, he is white by nature, and any POC so lucky to make the list is then white by extension.

Conversely, white supremacist publishing mandates that a list of “Black authors” cannot be a list of authors – it is a list of Black people who happen to write books. It would therefore be a fundamental absurdity to put a White author on a list of Black authors – defeats the point of the exercise, violates the premise. It’s a dogma of control. The separation and isolation of Blackness and Black people from the physical literary objects they produce is one of the primary modes of segregation and apartheid in our contemporary system of publishing. Sure, a Black person can produce a (White) book, but a White book cannot possibly think to reproduce Blackness. By alienating the Black writer from authorship, White supremacist publishing lays the ideological and methodological groundwork to further the alienation of the Black person from Whiteness – power, domination, economic reproduction and stability.

In retrospect, this was beyond a doubt the biggest flaw with 15 Black Transfeminine Novelists You Should Read, my previous attempt to chronicle the landscape of Black transfeminine publishing. While that article was groundbreaking, it was fundamentally constrained by the fact that it was a list of authors, not books. My decision to include cover photos of the books instead of author headshots mitigated this to some extent – but nevertheless.

Let’s take a concrete example from the early era of Black transfeminine contemporary publishing. We have concrete evidence that Roberta Angela Dee was a trailblazer and a community pillar in the late 90s and 00s. Roberta influenced Monica Roberts, the creator of TransGriot, and that Monica’s work with TransGriot and collaboration with Roberta helped to launch the literary career of 00s novelist Pamela Hayes. That is a very direct, traceable lineage of literary protogenesis that still has its echoes today.

Here’s a fun fact about Black transfeminine literary history: both Roberta Angela Dee and Pamela Hayes published novels in 2002. Did Sasha and The Lie have any influence on each other? Were they written in concert? Were Hayes and Dee in community with each other? Had Hayes read Dee’s earlier work before commencing her debut novel?

I have no idea. And frankly, short of finding Black trans women involved in Monica Roberts’ circles at the turn of the millennium who miraculously happen to be alive after a quarter-century, I do not have the slightest idea of how I could go about finding that out.

The funny thing with White transfeminine publishing is that the connections are often blatantly obvious. Everybody has read Nevada (everybody being White trans women in NYC in the 2010s and their various adjunct circles). Nevada has a very obvious archetype of the older transwoman/younger egg; Nevada has two extremely iconic locations in Brooklyn and Nevada; Nevada has messy internet screeds that still get riffed on, and metaphors about trans identity that still get lifted, and little quirks that pop up in the works of dozens of transfemmes who came out of the Topside diaspora. It was the book itself that influenced an entire generation.

What novel by a Black transfeminine novelist on that list from October could say the same?

And so there is a strange agony of forbearance here; one wishes to disrupt this vicious double bind that the mechanisms of White supremacist publishing has created, and yet a proper chronology of a “Black transfeminine literature” is entirely impossible to reconstruct, because we have absolutely no proof that any of the authors read each other’s books, or even knew the others existed! The deauthorialization of the Black transfeminine writer is a self-enforcing paradigm precisely because of this alienation – to posit that there is such a thing as the “Black transfeminine author,” the chronology must be ordered through the Black body instead of the book. It’s no literary history at all – nothing more than another matriline, which is the only form of Black womanhood that most White Americans have ever known.

It doesn’t exist, says the trans cynic. It doesn’t exist, says the white bigot. It doesn’t exist, says the Black transfeminine author working alone, shouting out into a void that never stops echoing back at her.

And so there is no such thing as “Black transfeminine literature,” which is how we got all the way to 2024 with authors still stuck in that same disorienting mode of isolation and separation as their Black peers in the late freaking 90s.

And let’s be clear – there have always been underground conduits. Roberta Angela Dee was doing it in the 90s. Monica Roberts was doing it in the 00s. Jamie Berrout was doing it in the 10s. Benjanun Sriduangkaew is doing it now for Bailey Saxon and Malaika Kirkwood, the two 2025 debut authors on the list I’m gonna share with you later, and fuck, Benjanun’s not even trans.

Presences never recorded. A record, never present.

Whose Springtime?

Trans writers might once have felt like we were writing in a vacuum, scratching about for ancestors. If there’s something distinctive about this moment for trans writers it is the thickening of our culture, the expansion of the archive from which we can draw.3

One of the truths I’ve found over the last few months is that McKenzie Wark and I disagree a lot, often in very predictable ways. I have an enormous amount of respect for her work, which is structured in such a way that simply invites this sort of polemical questions. Her essays provoke good discourse, even if that friction comes from contrast.

For the entirety of my research period before The Transfeminine Review went live, McKenzie’s 2020 essay “Girls Like Us” was my constant theoretical companion and bother. This was back when books like Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars and Little Fish were still new terrain for me – I was on the same reading journey I’ve watched many others go through over the last few months, and “Girls Like Us” was the piece of literary criticism that carried me through it. For those who’ve been following my work for a few months, you’ll probably remember that I offered a fairly in-depth critique of that piece on the first essay I published here, last August’s “The Problem with Contemporary Transfeminine Literary Criticism.” Here’s a brief excerpt of my take on McKenzie’s trans literature at the time:

Wark presents a picture of the development of transfeminine literature that proceeds from memoir (our lived experiences) to theory (assessments of those lived experiences) to fiction (interpretations of those assessments). It is a fairly compelling view, and one supported by most current narratives about transfeminine literature. I also believe that it is wrong. In many way, this narrative relies on the premise that “our” literature arises as a response to “their” literature, AKA the faceless transphobe, TERF, gender novel writer, or general malcontent who relishes in the schadenfreude of trans pain. Its critical flaws are outsourced to an oppositional dichotomy against the cisgender literary foil. Certainly there are examples which back this up – again, one of the most prominent purveyors of this mythology is Sandy Stone, as “The Empire Strikes Back” was written in response to transphobic personal attacks by Janice Raymond, the text which would go on to create the field of trans studies. With the majority of trans scholarship arising out of the trans studies context, scholars of contemporary transfeminine literature have, to this point, sought to apply the same methodological approach from trans studies to a literary application and understanding of transfeminine fiction. In many way, this work has almost resembled a copypasta of trans studies’ homework:

“Trans

StudiesLiterature was created as a brave and defiant response bySandy StoneTopside Press and Imogen Binnie to transphobicattacks by Janice RaymondGender Novels and the old-fashioned transsexualmedical interviewmemoir, and has since become the fertile ground for imagining new and unprecedented possibilities for trans people inacademiapublishing. For the first time, our stories are being told by us instead of cisacademicswriters.”Or so the story goes, at least.4

Harsh! And certainly easier for the Beth who didn’t personally know McKenzie to write than the Beth who now knows a significant majority of all the transfemme authors and academics in the field. I wanted to ruffle feathers and get attention – which I did – but the polemical tone here really obfuscates how useful I found “Girls Like Us” in my research.

Ultimately, I think that my point – that our literary history has an unbroken chronology of trans authors taking direct inspiration from the texts of other trans authors – and McKenzie’s point – that our literary history can be articulated as an antagonistic struggle with the normative hegemony of cis publishing – are entirely compatible with one another. The world has changed since we wrote those contrasting articles – 2025 isn’t 2024 by a long shot, and it’s certainly not 2020 anymore. Fascism is on our doorstep and we all need to adapt. McKenzie’s found new verbiage for her thoughts about trans literature in “Trans Fem Literary Springtime,” so I wanted to take the opportunity to re-articulate my critique in more refined terms, and perhaps strike a little closer to the true heart of the issue.

One aspect of “Girls Like Us” that I don’t think I engaged with nearly enough last time was McKenzie’s interesting and nuanced take on the conflux of transliterary antagonism and race. It’s interesting to go back and reread her prior thoughts on Juliana Huxtable’s work having now read her 2024 book Raving, which engages much more deeply with Juliana’s work. In 2020, she wrote:

You could read Juliana Huxtable’s Mucus in My Pineal Gland as poetry or as autofiction prose. The prose swings, as we found that time I lay on your bed performing the title piece while you improvised jazz chords. The self that addresses the reader is clockable as Juliana. The situations she traverses meddle real and imaginary, from hook-ups with white boys in suburban Texas to the delirium of New York nightlife. The surviving and thriving tactics of a Black trans woman are corporeal and psychic all at once, in and against this cracked-mirror funhouse America.

Then in the summer of 2020, a few months into the pandemic, the demand that Black Lives Matter erupted into the streets. For an event called Brooklyn Liberation for Black Trans Lives, fifteen thousand people came. This is another kind of writing, whose words are bodies, whose pages are streets. A writing that breaks sideways not only from the formal white agendas of queer institutional culture, but from any possible trans femmunism that hasn’t confronted how race cleaves us. To transition not only within the cis world but also within anti-Blackness is to tempt the whole world to murder. When Juliana Huxtable was asked about the nastiest shade she had ever thrown, her answer was: ‘Existing in the world.’5

I’ve been frustrated with this passage since the first time I read it way back in early 2021, specifically this pervasive idea in both Trans Studies and trans lit alike that the transsexualized body in and of itself is a form of text, a quasi-extension of the books it produces. In my August essay, my tack against this idea largely followed in the spirit of Andrea Long Chu’s critiques of Trans Studies in “After Trans Studies.” One can trace this body-as-text idea to the post-structuralist roots of Trans Studies, to Sandy Stone and Susan Stryker.

Sandy Stone’s contribution:

In the case of the transsexual, the varieties of performative gender, seen against a culturally intelligible gendered body which is itself a medically constituted textual violence, generate new and unpredictable dissonances which implicate entire spectra of desire. In the transsexual as text we may find the potential to map the refigured body onto conventional gender discourse and thereby disrupt it, to take advantage of the dissonances created by such a juxtaposition to fragment and reconstitute the elements of gender in new and unexpected geometries.6

Susan Stryker’s contribution:

By speaking as a monster in my personal voice, by using the dark, watery images of Romanticism and lapsing occasionally into its brooding cadences and grana gorgeous stylized tree-person playing a mandolin with branches-hair and dark skin, surrounded by glowing white butterflysdiose postures, I employ the same literary techniques Mary Shelley used to elicit sympathy for her scientist’s creation. Like that creature, I assert my worth as a monster in spite of the conditions my monstrosity requires me to face, and redefine a life worth living. I have asked the Miltonic questions Shelley poses in the epigraph of her novel: “Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay to mould me man? Did I solicit thee from darkness to promote me?” With one voice, her monster and I answer “no” without debasing ourselves, for we have done the hard work of constituting ourselves on our own terms, against the natural order. Though we forego the privilege of naturalness, we are not deterred, for we ally ourselves instead with the chaos and blackness from which Nature itself spills forth. (12)7

This is the part of the essay where we state the obvious: I am white. McKenzie Wark is white. Susan Stryker is white. Sandy Stone is white. Up to this point, to the best of my imperfect knowledge, any real attempt to have a discourse about Black transfeminine fiction has largely been taken up by non-Black literary critics, with all of the pitfalls and problems that come with that.

What all of these theoretical stances implicitly posit – Wark, Stryker, Stone – is that there is a strong symmetry between the disenfranchisement from authorship of Black writers and trans writers. To be clear, I do think there’s merit to this approach – but it does not fully explain the nuances of anti-trans discrimination in publishing, nor why Black transfemmes face such unique challenges in the industry. Note that Stryker’s take positions textual trans monstrosity as an “alliance” with the “chaos and blackness” of “Nature” – the confluence of trans text and Black text is a juxtaposition, not a self-sameness, and all of these white theory texts place trans text at a certain remove from the “Nature” of blackness and, unspoken, Black bodies.

Now, we don’t have time to unpack the racist history of the concept of Nature, but. Well.

When McKenzie Wark develops her concept of “autofiction” as the production grounds for the emergence of a transliterary discourse, I want to draw your attention to how she specifically figures the form of it against the Black body: “This is another kind of writing, whose words are bodies, whose pages are streets.” That’s not the body of the Black author; it’s the body of the Black protestor – and not even the lone protestor, the civil rights protester, the body en masse. What Wark seeks to do in “Girls Like Us” is to meld together these allied forces of trans literature and Black authorship; in essence, to mush them together into an autofiction which takes on the traits of both. But it’s authorship taken from Black authorship, not Blackness. The fundamental figure of the “author” is still white by default.

What this produces ultimately is a certain dislocation where the disenfranchisement from authorship for Black writers is presented as the historical challenge of transliterary discrimination, and then the emergence of a trans (White) authorship as text is forwarded as the proposed remedy to this rupture of history.

This is my true frustration with dialectic of transliterary history that Wark presented in 2020. I find it extremely ironic, of course, that that essay was published in The White Review.

Here’s a fact – we can trace a direct genealogy of White transfeminine fiction all the way back to 1893. We have many examples of direct literary influence from one generation of White trans writing to the next. To then posit the emergence of Black transfeminine literature at the end of that genealogy therefore not only implies Black transfeminine authorship as an outgrowth of the emergence of a normative White trans publishing industry, but also elides the fact that contemporary Black transfeminine authors are still alienated from authorship and literary history much as they have been in decades prior.

Let’s take a different tack. Black transfeminine publishing has always existed as a supplement to White transfeminine publishing, a neglected undercurrent to be extracted and discarded, forgotten. Even now, at the nadir of the contemporary trans publishing movement, it remains a counterweight and a benchmark upon which White trans publishing may be weighed. It is no less fragmentary now than it was in the 1990s, when Roberta Angela Dee was silently toiling at powerful literary fiction while Reluctant Press churned out white erotica slop around her, or when Yemaya’s Daughters was also self-published in 2013 and received little of the attention or acclaim of its White transliterary cousin Nevada. Even now – what books are favored for literary preservation? How many of the participants of the Trans Literature Preservation Project have more than one or two Black transfemme-authored novels in their library?

This isn’t just a question of positing that Black transfemme lit isn’t in all that different of a place as it was thirty years ago – it’s a question of positing that White transfemme lit isn’t in all that different of a place as it was thirty years ago either. The economics, tropes, genres, and volume have all shifted, but the primary modes of conceptualization and reproduction have not. Crucially, my thesis here is that the relationship between White and Black transfeminine literature has barely shifted during that time, if at all. There’s more of both, but that hasn’t changed much structurally of what it means to be a White transfeminine author or a Black transfeminine author.

The ‘Transgender Tipping Point’ was always a myth, one which excused the White desire to posit the gains of the Trans Liberation movement as equally distributed across demographics. And thus White supremacist publishing legitimates itself through a new lens, and the cycle begins again.

White Hegemony in Publishing

Circling back around the “Trans Fem Literary Springtime,” Wark’s latest essay. There’s a really interesting discourse here about literary authority, which I think is notably and markedly different than how I’m using the notion of authorship. I’m gonna quote a fair chunk of it so you can get a sense of the part of the essay that’s caught my interest:

There’s something so bittersweet in this springtime for trans writers. Publishing lags a bit behind the times. For mainstream publishers, maybe it seemed like we were the next thing to add to the diversity playlist in the search for a market. The Great American novel by the Great White Man just isn’t a thing anymore. No matter how much hype the last Cormac McCarthy books got, not many people bought them.

The decline in the authority of the author is not a bad thing. That authority was premised on the assumption that “the others” didn’t read, or if they did, their (our) critical perspective wouldn’t matter. McCarthy could cartoon transness in The Passenger, as David Foster Wallace did in Infinite Jest, because in the synoptic world of the Great Novel we’re just emblems, incidentals, props.

The undoing of the authority of the author proceeded through the dissent of women readers, nonwhite readers, queer readers, and the formation of counter-literatures. Some of which, with some adaptation, became components of a replacement version of commercial literature. One can see the inclusion of trans writers within the field of the literary as a late development in that cycle.

The question is whether it will survive the repressive turn that’s gathered speed and fury in recent years. Public libraries, public-school reading lists, and university courses that center Black or queer or trans writing are up for purging. It’s likely we’ll be pushed back out of public life. I’m not the only one who sees signs of that already.8

Important caveat – McKenzie’s use of ‘authority’ here is clearly informed by Andrea Long Chu’s forthcoming essay collection of the same name, which she has read and also discusses in this essay but I have not. So bear that in mind.

In this moment of cultural backlash and rapid loss of civil rights, there is a certain seductive pull toward autopsying the failures of the Progressive movements in America of the 2010s. Were I to take a moment and indulge, I might hypothesize that aesthetic movements like #OscarsSoWhite and #OwnVoices relied far too heavily upon Twitter activism and visible performances of diversity, creating spectacles of marginalized art without actually addressing the underlying systemic causes of those inequities. They created marketing demographics, not institutional change. One might also argue that, much as the #MeToo movement was coopted by carceral white feminisms that posited the end-all, be-all of responding to sexual assault by powerful men was to send said men to prison, #OwnVoices was an appeal to a White supremacist publishing industry that demanded inclusion in those institutions rather than advocating economic justice for the poor, disabled, racialized, transfeminized populations who so often lacked access to it. In this alluring presentist mode, we might be tempted to thus conclude that Progress(tm) was made in the last decade, and that had we just avoided the mistakes of the 2010s, perhaps the publishing industry would support all marginalized populations right now!

While it’s important to linger on this view – particularly in recognition that #MeToo, #OscarsSoWhite, and #OwnVoices did produce real material gains for marginalized populations, real gains that are now being actively erased – I think it’s more important to understand what hasn’t changed over the last decade than what has come and gone. Authority is a really compelling world for understanding what these movements were trying to accomplish. It was the authority for a victim of sexual assault to challenge her abuser. It was the authority for Black critics and actors to have a say in industry certification. It was the authority for an author of color to have their book recognized under the vaunted title of ‘literary fiction, or included in a prestigious award like the Women’s Prize for Fiction, as Detransition, Baby was. But in all of these cases, ‘authority’ manifested as a rebalancing of structures of institutional power which already existed, NOT the creation of new ones.

I would argue that this is the key difference between ‘authority’ and ‘authorship.’ White supremacy in publishing may be enforced by the authority of white men, but that’s not what makes publishing itself a White supremacist institution.

When I’m talking about ‘White supremacist publishing,’ I mean it in the sense that the core product of the publishing industry is not the book, but the author. Publishing dictates and legitimates authorship itself, and its power largely rests upon its continued control and direct ownership of the social category, not the texts it produces. It’s the reason why your ‘debut novel’ is the first tradpub book, not the first book you’ve ever made money on (AKA basically the entire reason Alyson Greaves ridiculously won the ‘Best Transfeminine Debut’ award for a book published in 2022); the reason why your novella makes you an author but your fanfiction doesn’t; the reason why many bookstores are physically incapable of stocking many self-published books. The publishing industry is white supremacist because the fundamental tenets of how it creates the ‘author’ as a social and economic actor are structurally disposed to favor white bodies over brown and black bodies for the role.

The publishing industry happily went along with lots of #OwnVoices suggestions in the late 2010s and early 2020s because despite benefiting marginalized authors already within the system, none of the activism fundamentally challenged their hegemony over the dictums of authorship itself. It’s the same reason why, being less economically viable under a Trump dictatorship, the publishing industry has already begun to scale those same measures back. White supremacist publishing does not have a moral compass. It is not a person or a feeling entity. Its entire purpose is to protect and reproduce its stranglehold over authorship, and it will act in whichever way best upholds that goal, whether its greatest pressure comes from the Left or the Right.

In a society where Black Americans have been systemically stripped of any and all economic advantage, in a society where having black skin once meant (and still can mean) that another person owns you, in a society that still balks at the first signs of economic justice – Black authorship is a fundamental challenge to publishing’s monopoly on the category of ‘author’ precisely because it shifts the notion of ‘author’ away from the concentration and control of capital.

Publishing is not white supremacist because the institution itself is ‘malicious’ or ‘evil’ – it is White supremacist because authorship is a means of economic production, and we live in a Western society that will withhold that from people of color at any and all cost.

So it’s fine for an #OwnVoices author to receive a Pulitzer or a Hugo, as long as the publishing industry is the one making royalties off their work. It’s fine for a Black author to receive a huge book deal, so long as their agent is the one who negotiated it. It’s fine for a Black author to become massively famous on social media or TikTok, because their voice and message is being conducted through a platform approved by the powers who be.

It’s a paradigm of exploitation.

McKenzie Wark does discuss one upcoming book by a Black transfeminine author, When the Harvest Comes by Denne Michele Norris. I’ll clip the discussion here (it’s brief):

Denne Michele Norris’s When the Harvest Comes (Random House) is about race, sex, and grief. Mostly grief. Davis, the central character, left home after his father found him getting fucked by a white boy. He falls in love, and intends to marry, Everett. It seems like Everett’s close, rich, white family is liberal minded about the whole thing. Until Everett’s little brother says the quiet part out loud: they can accept this gay interracial marriage because they assume—correctly as it happens—that Everett fucks Davis, not the other way around.

The death of Davis’s father, the Reverend Doctor, sends him spiraling. They may be estranged, but the Reverend Doctor is the one who set Davis on his path, as a topflight classical viola player. The book is an elegant account of the complicated grief we can feel for family with whom we’ve had to break—an experience all too common for transsexuals.

That Davis plays the viola is connected to an incipient transsexuality that Davis isn’t quite ready to let out. Unlike a violin or cello, the body of a viola is too small for its acoustic range, leading Davis to remark: “I’m saying I identify with that aspect of the viola—the built-in flaw, the very real limitations to the body in which I navigate the world every day.” And yet he—soon to be she—makes beautiful music with it.9

It’s fine. Doesn’t have much to say – for the most part, it’s just a plot summary with a little bit of commentary. I can’t help but feel it’s a bit perfunctory; that its inclusion does not add anything to the discussion other than to flesh out the list with a Black-authored book for flavor.

Why was this book included, but none of the others on this list? The answer is simple – Denne Michele Norris has a rigorous claim to industry certification and formal authorship, while many of the other authors on the list in the next section don’t. Denne is the first black trans woman to helm a major publication – she’s the Editor-in-Chief for Electric Literature, and has edited several other lit mags in the past. She’s represented by a team of three people: Robert Guinsler is her agent, Carrie Niell is her publicist, and Leslie Shipman manages her speaking engagement. Denne’s book deal for When the Harvest Comes was on the Random House imprint, literally the central imprint of Penguin Random House, and her anthology of trans of color essays this summer Both/And is getting published by HarperOne, one of the core imprints of another Big Five publisher, HarperCollins.

To be absolutely clear, this isn’t a criticism of Denne Michele. I’m thrilled that she gets her bag. It’s important to remember that structural issues cannot be distilled down to individual actions – we have to be able to separate our recognition of particular cases of structural injustice from our discussion of why those cases come about in the first place.

I’m not criticizing McKenzie herself either. Nothing that McKenzie Wark did set out to ‘do’ White supremacy in publishing in any way, shape or form. This article isn’t calling her or her work ‘racist’ – that’s a total misconstruction of my argument. McKenzie wrote a really interesting piece of criticism for a literary magazine that openly and compassionately discusses a multitude of novels from TWOC and takes meaningful time to highlight and champion their accomplishments, and that’s awesome! That doesn’t change the fact, however, that the core exercise of “Trans Fem Literary Springtime” is one curated and structured by the hegemony of authorship and a White supremacist publishing industry, and that in participating uncritically in such an exercise, it becomes extremely challenging not to reproduce the structural understandings of authorship that disempower Black authors and other TWOC and marginalized trans authors from economic reproduction in the first place. My issue is with the nature of the exercise, not the author.

McKenzie herself is upfront about the duty she’s performing for the publishing industry:

In this roundup, I’ve left out books by trans men, nonbinary people. I’ve left out genre fiction and poetry. I tried, but I did not even get to all the literary fiction and nonfiction books by trans women that have been announced. And then there’s a whole other community of self-publishing trans writers and their reading communities. There’s too much for one person to cover—at least for now. No matter what, trans people will keep on writing, and finding ways to connect to readers. We’re not going away.10

There’s nothing wrong with wanting to focus on tradpub literary fiction from transfeminine authors. It’s a concrete inquiry and McKenzie explores it well. But an industry that only knows how to perform that type of analysis, an industry which often seems incapable of considering the “community” of self-publishing on the same platform as Penguin Random House or HarperCollins, structural inequities begin to arise.

There’s a long section about the history of trans lit, and I can’t be the only one who noticed that all the books in that section came from white authors. That’s not an intentional choice; it’s because if you examine trans publishing solely from the lens of traditional publishing and industry-certified indie presses, the only real rigorous ‘literary history’ you’re gonna be able to reconstruct is a white one. By contrast, the inclusion of When the Harvest Comes feels somewhat auxillary because you literally can’t talk about Black transfeminine literary history if you’re only looking at it through that lens. There’s what, LOTE? LOTE and When the Harvest Comes might as well be different genres with as much as they have to do with each other. There’s literally no Black transfeminine novel you can refer it to, because all of the meaningful work by Black transfeminine authors has been done beyond the scope of the industry. And even if it were acknowledged, it’s largely irrelevant because Denne Michele herself didn’t come up in those communities; they were never mainstreamed, never legitimated, left unspoken by the public record of trans history.

I called Black transfeminine literature a “supplement” to transliterary history earlier with intention. We turn here to Derrida:

The thematic of history, although it seems to be a somewhat late arrival in philosophy, has always been required by the determination of Being as presence. […] History has always been conceived as the motion of a resumption of history, as a detour between two presences. […] For example, the appearance of a new structure, of an original system, always comes about – and this is the very condition of its structural specificity – by a rupture with its past, its origin, and its cause. Therefore one can describe what is peculiar to the structural organization only by not taking into account, in the very moment of this description, its past conditions: by omitting to posit the problem of the transition from one structure to another, by putting history between brackets.11

What work is When the Harvest Comes doing in “Trans Fem Literary Springtime” if Wark isn’t making any real arguments about its content or themes? Much as Black literary voices were used in “Girls Like Us” to propose the dialectical progression of autofiction five years ago in contrast to a white cisnormative literary past, I would argue that “Trans Fem Literary Springtime” uses the presence of Denne Michele Norris’ debut as a device to signify her argument of an expansion and deepening of the literary field, a shift in structure. Black trans literature is used in the White critical lens to indicate the emergence of a new structure of literary production – look, Black trans women couldn’t publish with the Big Five before, and now they can! Implicit in this indication (none of this is said on the page by Wark, though some critics are more explicit) is the colloquial understanding that there was not a Black transfeminine literature to be pointed to twenty years ago; its novelty is required to dislocate the White literary history from its ‘problematic’ past.

Remember that Susan Stryker speaks of the emergence of trans textuality as a twinning of blackness and chaos – this is the rupture, the figure of the Black body within White supremacist publishing is the necessary condition which allows for a “trans publishing” to emerge.

This is not a process that can only occur once. It must be reduplicated. Wark’s structural argumentation in 2025 echoes her structural argumentation in 2020, just as her argumentation in 2020 echoes Morgan M. Page’s 2016 review of jia qing wilson yang’s Small Beauty, which is one of the only places I’ve ever seen a white critic discuss Yemaya’s Daughters.

Wilson-Yang’s Small Beauty eschews the tired gender novel stereotypes, placing Mei’s connections to her trans sisters and discovery of hidden trans history within rural Ontario near the center of Mei’s emotional landscape. In this way, Small Beauty joins the small but growing numbers of trans-genre novels written by transgender women that are revolutionizing our ideas of how trans people can exist within fiction–including Dane Edidi’s Yemaya’s Daughters, Imogen Binnie’s Nevada, and Jamie Berrout’s Otros Valles.12

Denne Michele Norris, Juliana Huxtable, Dane Figueroa Edidi – the names cycle, but the theoretical move remains largely the same.

None of this scholarship is problematic if you consider it in the present moment, but I want you to think about how it comes together across the decades to produce a narrative. “Trans Fem Literary Springtime” is a continuation of a long history of White transfeminine publishing – a new connecting link that explicitly takes us back through Detransition, Baby, Topside, and earlier. But this type of scholarship grows increasingly useless for any scholar of trans of color literature the further you get from the present moment! Black transfeminine literature is only grounded insofar as it comes up in the purview of White transliterary history.

Imagine reading Wark’s essay in twenty years. What does it tell you about When the Harvest Comes, or Denne Michele Norris, or the present situation of Black transfemmes in publishing beyond the fact that they existed? Almost nothing. But we get context in the longue duree for the works of Torrey Peters and Jamie Hood, for Jennifer Finney Boylan and Andrea Long Chu.

Crucially, Derrida tells us that this rupture of (Black) presence must be contrasted by an absence or omission within the contrasted (anti-Black) structural past. And maybe that’s fine if Black transfeminine literature really is such a novelty, but it’s not. The only effect had by the unthinking and subconscious repetition of this intellectual move is that Black transfeminine authors are forgotten from the history the moment their work ceases to hold immediate relevance. Just as a White transliterary present cannot be figured without the presence of transliterary Blackness, the White transliterary past cannot be figured without the absence of it.

Supplementarity: always underlying, never within. Black transfeminine literature is a supplement because, despite how White transliterary history relies on its existence to articulate itself, leading to a contiguous trail of Black trans publishing going back decades, it is strictly impossible within the structural confines of White supremacist publishing for that literature to have a history of its own. Because the history of Black text is always external while the history of White text is intrinsic (Natural), the entrance of a Black transliterary text cannot be explained in trans-historical terms, which is how you get the sort of vapid acknowledgment When the Harvest Comes receives. One cannot propose its history without revealing the instability of the whole facade.

Unthinking a Transliterary Blackness

So, what’s to be done about all of this?

If you’ve never read it, I would highly recommend that you go read Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination by Toni Morrison, which provokes many of these same questions in the broader history of American racialized fiction. In my opinion, it should be mandatory reading for anyone who wants to take literary criticism seriously.

Morrison poses:

For reasons that should not need explanation here, until very recently, and regardless of the race of the author, the readers of virtually all of American fiction have been positioned as white. I am interested to know what that assumption has meant to the literary imagination. When does racial “unconsciousness” or awareness of race enrich interpretive language, and when does it impoverish it? What does positioning one’s writerly self, in the wholly racialized society that is the United States, as unraced and all others as raced entail? What happens to the writerly imagination of a black author who is at some level always conscious of representing one’s own race to, or in spite of, a race of readers that understands itself to be “universal” or race-free? In other words, how is “literary whiteness” and “literary blackness” made, and what is the consequence of that construction? How do embedded assumptions of racial (not racist) language work in the literary enterprise that hopes and sometimes claims to be “humanistic?” When, in a race-conscious culture, is that lofty goal actually approximated? When not and why? Living in a nation of people who decided that their world view would combine agendas for individual freedom and mechanisms for devastating racial oppression presents a singular landscape for a writer. When this world view is taken seriously as agency, the literature produced within and without it offers an unprecedented opportunity to comprehend the resilience and gravity, the inadequacy and the force of the imaginative act.13

There are so many people in the trans community who take an enormously fatalistic approach to history and historical becoming. Of course it was going to happen, it did happen, it’s a fact of life and cis people need to stop denying the truth about the past. History is natural, and naturalized within the White transliterary imagination.

They’re wrong.

Literary history doesn’t just happen – it’s made. That goes way beyond the writing and publication of books. Topside Press happened because people sat down together and organized and said, ‘Hey, let’s change the narrative on trans fiction.’ A book published into a vacuum is often dead-on-arrival – no discussion, no influence, and ultimately nothing to be remembered.

My point is that when White trans people are like ‘Oh, but you can’t just make up literary history, there’s not enough there to talk about’ – and it’s always other White folks – I find myself frequently biting my tongue on the obvious retort: ‘Well, yes, but that’s because people like you don’t have any interest or motivation to write it down.’ Just because White people have not observed the literary histories of TWOC hardly means they do not exist – look at the Trans Women Writers Collective and the enormous amount of organizing and publishing work they did for trans of color writers! That was less than a decade ago – where are all of the people who should be discussing it today?

In the strictest sense, a ‘literary history’ cannot begin until someone sits down and actually bothers to do the damn work of putting the books in conversation with each other. We do it for White-authored books all the time. But for racialized trans authors up to this point, especially Black, Latine, and Indigenous transfemmes, our literary critics and historians have utterly failed to take any sort of meaningful account of the themes, tropes, histories, productions, relations, influences, inspirations, or really anything about their works.

But that can’t happen unless trans criticism can unwind itself from the vice grip of the White supremacist publishing industry. That can’t happen unless our criticism can put traditional and indie and selfpub books in concert. That can’t happen unless we can give the relations between trans of color texts the same care and attention as White texts. It cannot happen, and it will not happen, unless people make a conscious, active decision to start unthinking our inherited structural assumptions from a cisgender publishing industry which, by and large, still very much does not care if we live or die.

*

Originally, this article was just supposed to be a reading list for Black History month lol. What I’ve collected for you here at the end of this article is the Black transfeminine fiction coming out over the next few months and years. Most of these books aren’t out yet, and I’ve only read one of them. The original concept of this article was just to get people excited about Black trans lit, and to get name recognition and pre-orders for some of these lesser-known authors.

What I want to do instead is to extend to you, my reader, an open invitation to join in on the productive work of literary history. Here is a body of work now that nobody has ever theorized or discussed in tandem. What do these books have in common? How were they published? What themes or ideas do they have in common? Do you think they do a good job at presenting their ideas?

The most powerful thing you can do is write those thoughts down and share them. Even a short, genuine review can be a powerful thing. By discussing these books, by writing essays, you’re beginning the work of creating transliterary history that doesn’t premise itself upon the supplementarity of the Black body as text.

I would ask you to go back and revisit 15 Black Transfeminine Novelists You Should Read and do the same thing there. Pick a couple, compare and contrast them. How do we understand this work as a group? Historically, how have these books moved through the normative White transliterary landscape? Why did so many of these books receive scant attention compared to their White-authored peers? What’s changed? What hasn’t?

There has to be friction to spark productive dialogue. My hope is that in publishing this article and making these books known to the world, I can help to light that flame.

Your 2025 Black Transfemme Reading List (and Beyond)

The Cosmic Color by T.T. Madden

Date: January 25th, 2025

Publisher: Neon Hemlock Press

Genre: Science Fiction, Mecha, Gundam

Website: https://linktr.ee/ttmaddenwrites

Bluesky: Link

Purchase: Neon Hemlock

CAN ANYONE ESCAPE THE MACHINERIES OF FLESH AND STEEL?

Eric Fisher, a Black recruit finishing up his training, has always felt strange in his own skin. Now that he’s finally a mecha pilot, ready to join the fight against the monstrous Imago, he gets to be in a body that feels more right. But this new sense of self and gender must be navigated while uncovering revelations about the machineries of flesh and steel he’s now a part of.

This is the only book on this list that’s out at time of publication, so you should start here and bookmark this page so you can keep coming back to it throughout 2025! I had the pleasure of reading The Cosmic Color today, and let me tell you, it’s a delight. Transhumanist feels, a wonderfully well-realized protagonist, and flavorful prose all make this an excellent (short) read. At 99 pages from last year’s winner of the TFR Indie Press of the Year Award, DC-based Neon Hemlock Press, I would highly recommend checking this one out <3.

If you want to read my full review of this book, it’s posted on my Patreon now.

Cabin Fever by Jack Harbon

Date: March 11th, 2025

Publisher: Self

Genre: Erotica

Website: https://jackharbonbooks.shop/

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: Jack Harbon Books

When Jayden’s father falls ill from a questionable gas station sushi roll, he reluctantly takes the man’s spot on his company trip. He’d much rather stay in the safety of his bedroom, distancing from the world and stewing under his own rain cloud. But the trip up to the cabins isn’t all bad; he’s rooming with three of his father’s sexiest employees, and after a shocking and voyeuristic late-night discovery, Jayden soon begins to understand why these three are so eager to return to this cabin every year. Team-building exercises have never been so downright filthy, and with a little help from the guys, Jayden just might start to take action and get himself out of his own seemingly-endless despair.

Jack Harbon was one of the few authors I didn’t manage to sample when putting together my last list, but I know for a fact that her books are a proper M/M steamfest. Cabin Fever will be releasing a week earlier on her website than it will on Amazon, so if you want to get the book early and flip it to the evil empire, I would highly recommend preordering it at the link above.

Song of the Dryads by Bailey Saxon

Date: April 1st, 2025

Publisher: Self

Genre: Fantasy

Website: https://www.patreon.com/BaileySaxon

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: itch.io

Gayle is a lonely man. A strong and well respected one, but alone nonetheless. He decides to put this strength to good use and investigate a string of suspicious hunter deaths. Each case reeked of foul play from more experienced hunters, numerous newbies going missing after going on request to gather materials from the forest with them. He ventures in, the determination to save who he can overriding his fear.

Bianca, the new girl in the forest, has a dark secret that she can’t let a single Dryad in their secluded sequoia grotto know. They all love and respect her, but she worries that kindness could disappear all in a matter of seconds. Dryads are known for their affinity to nature, so she strives to make herself indispensable by helping everyone out. They saved her from being alone, and she can’t tell them why or she may lose the community she so desperately wanted all along.

Follow the titanium egg of the century in her magical journey to find herself, her family, and her own definition of the meaning of life.

Benjanun’s wonderful cover art and support for self-published transfemmes of color strikes once again. Bailey is such a sweetheart, and I have no doubt that her debut novel will glow with it. She also is trying to raise money for gender-affirming care, if you want to support her fundraiser.

When the Harvest Comes by Denne Michele Norris

Date: April 15th, 2025

Publisher: Random House

Genre: Literary Contemporary

Website: https://www.dennemichele.com/

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: Bookshop

The venerated Reverend Doctor John Freeman did not raise his son, Davis, to be touched by any man, let alone a white man. He did not raise his son to whisper that man’s name with tenderness.

But on the eve of his wedding, all Davis can think about is how beautiful he wants to look when he meets his beloved Everett at the altar. Never mind that his mother, who died decades before, and his father, whose anger drove Davis to flee their home in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, for a freer life in New York City, won’t be there to walk him down the aisle. All Davis needs to be happy in this life is Everett, his new family, and his burgeoning career as an acclaimed violist.

When Davis learns during the wedding reception that his father has been in a terrible car accident, years of childhood trauma and unspoken emotion resurface. Davis must revisit everything that went wrong between them, risking his fledgling marriage along the way.

In resplendent prose, Denne Michele Norris’s When the Harvest Comes reveals the pain of inheritance and the heroic power of love, reminding us that, in the end, we are more than the men who came before us.

If there’s a blockbuster release on this list, it’s this book. Denne Michele Norris’ debut is literary fiction, coming out on the Random House imprint to a mass audience, and let me tell you, this one’s gonna make waves. I will be reading it the day it comes out.

One Day in June by Tourmaline

Date: May 20th, 2025

Publisher: G.P. Putnam’s Sons Books for Young Readers

Genre: Children’s Book, Picture Book

Website: n/a

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: Penguin Random House

You wouldn’t even believe the things Saint Marsha used to get up to—she had more of a zest for life than anyone I’ve ever known, and the biggest heart, too.

It’s a hot summer day and New York City is buzzing like a hive of eager honeybees. From Riis Beach to the Flower District, into the West Village and over to the Brooklyn Museum, folks young and old embrace the resolute and love-filled spirit of icon activist Marsha P. Johnson in all that they do.

Told through the eyes of an old friend and with bright, buoyant artwork, this jubilant story celebrates the indelible stamp that Marsha P. Johnson left on New York City and beyond, culminating in a powerful convergence one day in June 2020, when activists from across all five boroughs rallied loudly for Black trans lives.

Tourmaline is also releasing her long-awaited biography of Martha P. Johnson on the same day as this adorable little book for young kids, but I haven’t seen nearly as much discussion of this one. There’s a serious paucity of quality kidlit for trans kids, so I would definitely recommend this one to the parents in my audience.

Gorman’s House by T.T. Madden

Date: September XX, 2025

Publisher: Mad Axe Media

Genre: Horror, Young Adult

Website: https://linktr.ee/ttmaddenwrites

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: not yet

Inspired by creepypastas, the Backrooms, and analog horrors. On Halloween night, a group of teens hear that the fabled Gorman’s House is in town; a traveling haunted attraction that’s supposedly so scary no one has ever completed it to claim the prize money.

But they soon discover this haunted attraction contains real supernatural frights.

Did I mention that T.T. Madden has no fewer than three novellas coming out this year? If they aren’t in contention for Breakout/Debut Author this December, I’m gonna riot lol.

The Comfort of the Knife by Malaika Kirkwood

Date: 2025 TBD

Publisher: Self

Genre: Urban Fantasy, Cultivation, Post-Apocalyptic

Website: https://www.patreon.com/mxoberon

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: not yet

When humanity first formed contracts with eldritch beings from the other side of reality to gain sorcery, the first thing they did was destroy the world. The second, was make a new one.

Scarred by the murder of her father, Nadia intends to die avenging him, beginning a journey that will require her to form a contract with a goddess of a razed court, and join an order of the greatest killers in the world.

But when allies become lovers, Nadia’s new reasons to live compete against her desire to die, leaving her with a choice to make: give up on vengeance or see her quest to its bloody end. . .even if it means cutting a path through the ones who love her.

Malaika Kirkwood is the second debut author on the list this year! The Comfort of the Knife is currently being serialized over on Royal Road if you want to check that out before the published edition later in 2025.

The Neon Revelation by T.T. Madden

Date: November XX, 2025

Publisher: Timber Ghost Books

Genre:

Website: https://linktr.ee/ttmaddenwrites

Bluesky: Link

Preorder: not yet

The Neon Revelation by TT Madden follows Roan, a transwoman looking for revenge who infiltrates a mysterious religious community who claims to have miracles. The lovechild of Outer Range and Immaculate, The Neon Revelation asks why we worship the people and institutions we do, whether the sacrifices they ask of us are worth it, and how what they say are sins might just be our only road to salvation.

And here’s the third T.T. Madden novella.

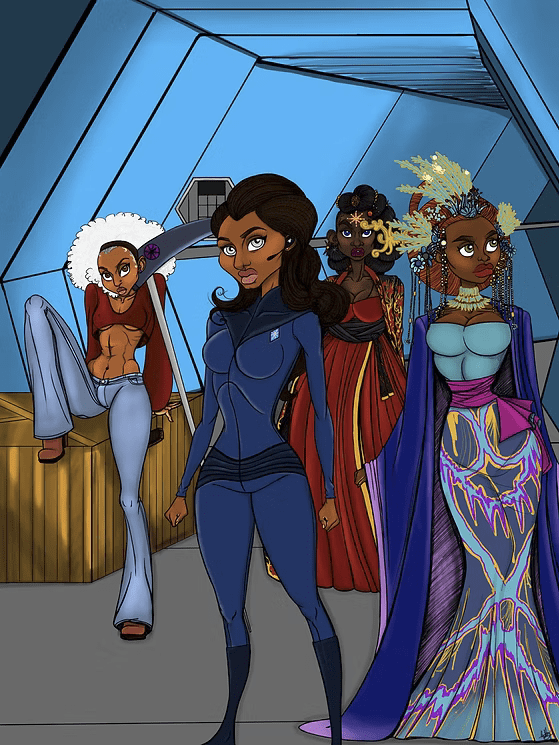

She of the Fallen Stars by Dane Figueroa Edidi

Date: Fall 2026

Publisher: Self

Genre: Science Fiction

Website: https://www.ladydanefe.com/

Instagram: Link

Preorder: Dane’s Website

The year is 4000 and the Universe has finally found some semblance of peace.

On Earth, to maintain a lasting peace amongst humans, Princess Amina of New Ifa prepares to leave her home in the United Nations Of Africa to become a concubine of the Patriarch of the Thirteen Colonies in the West, while in The Prison Colony, Tiye and her lover Amon find themselves in a race against time to try to save their fellow inmates from certain death.

Meanwhile in the cosmos, a group of Trans Space Pirates led by the mysterious Lady Ki wage a covert war against a shadowy organization bent on controlling the Universe, while Sister Iyanna, a Pleasure Priestess, finds herself drawn to a mysterious new planet.

But, when a prominent power player in Universal politics is assassinated all four women find themselves at the center of a celestial Conspiracy spanning several lifetimes.

Will the Universe plunder itself back into war? Will Aliens conquer the Earth? Will four women from across the cosmos be able to stave off impending doom?

I don’t know about you, but I am so excited about this book – it’s already one of my most anticipated releases of 2026! But that feels like millions of years away right now.

Collected Psalms by Dane Figueroa Edidi

Date: Spring 2026

Publisher: Self

Genre: Fantasy

Website: https://www.ladydanefe.com/

Instagram: Link

Preorder: not yet

No blurb yet.

I know absolutely nothing about this book, but Lady Dane brought it up when I emailed her about details on She of the Fallen Stars, so here it is!

A Note from Our Sponsors!

Before you go read some of these incredible books, I wanted to take a moment to announce that we’ve officially launched a Patreon account for The Transfeminine Review! If you want to help me continue doing this critical work fulltime, and if you found this article valuable, please consider supporting our work with a monthly subscription. I’ve begun posting a review for every book I read over there, so Patreon is the best place to keep track of my latest reading :))

If you subscribe at the Sponsor tier of above, your name will be listed on our Sponsors page ❤

Thank you for reading – now go forth and support Black transfeminine authors!

- Raquel’s recent arrest. Wilkinson, Alexa B. December 5th, 2024. Washington, DC. You can follow Alexa on Bluesky here: https://bsky.app/profile/alexabwilkinson.bsky.social ↩︎

- Berrout, Jamie. Incomplete Short Stories and Essays. Self, 2015. 164. ↩︎

- Wark, McKenzie. “Trans Fem Literary Springtime.” e-flux Notes. January 8th, 2025. https://www.e-flux.com/notes/648500/trans-fem-literary-springtime ↩︎

- Karsten, Bethany. “The Problem with Contemporary Transfeminine Literary Criticism.” The Transfeminine Review. August 27th, 2024. Link. ↩︎

- Wark, McKenzie. “Girls Like Us.” The White Review, December 2020. https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/girls-like-us/ ↩︎

- Stone, Sandy. “The Empire Strikes Back: A Post-Transsexual Manifesto.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 231. ↩︎

- Stryker, Susan. “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Preforming Transgender Rage.” In The Transgender Studies Reader, edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, 2006. 254. ↩︎

- Wark, “Springtime.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978. 291. ↩︎

- Page, Morgan M. “Small Beauty” by jia qing wilson-yang.” Lambda Literary Review. May 9th, 2016. https://lambdaliteraryreview.org/2016/05/small-beauty-by-jia-qing-wilson-yang/ ↩︎

- Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. New York: Vintage Books, 1992. xii-xiii. ↩︎

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.