Before we begin – The Transfeminine Review is now on Patreon! If you want to help us continue to produce vigorous public scholarship like this, please consider supporting us there.

This article was made possible by our Sponsors!

Note: this is a very long article (around 47,000 words) so please use the table of contents below to help navigate. Also, just a general trigger warning for all of the slavery, genocide, and other horrors that come with the Antebellum Period. It’s grim.

- The Trojan Horse of Modern Conservatism

- The Birth of Fascist Censorship in the Deep South

- Deportation and Ethnic Cleansing in 1830s Missouri

- St. Louis, MO: America’s First Crossdressing Ban

- New York State: Revolt, Repression, and the Myth of the ‘Masquerade’

- Columbus, OH: Popular Sovereignty and the Election of 1848

- The Dred Scott v. Irene Emerson Case of 1838

- Bentonites, Barnburners, and the Democratic Schism over Slavery

- Dickinson, Cass, and the Convention of 1848

- How the Democrats Flipped Ohio in 1848

- Ohio’s Original Constitution

- The Marion Riot of 1839

- The Jones v. Van Zandt Case of 1847

- The State of Ohio v. Forbes and Armitage Case of 1846

- Ohio’s New Constition and the Expansion of the (White) Judiciary

- Nashville, TN: “The Grand and Noble Scheme”

- Chicago, IL: Black Laws and the Birth of a Nation

- Support Our Work

This is the fourth essay in our A Brief History of Transfeminine Literature series. You can find the first essay “The Moral Origins of Obscenity” here, the previous essay “American Evangelicalism and the Ineptitude of the Whig Party” here, or a complete series listing at the end of the essay.

The Trojan Horse of Modern Conservatism

Transphobia – it is a political imperative, a legal ideology, and it has not always existed. Just 200 years ago, anti-trans sentiment was far less articulate or cohesive than it is today. As with any legal movement, the origins of anti-trans law in the United States can be directly traced, and doing that work is absolutely crucial to anyone seeking to fight back against it in our modern day.

Writing this article has been a struggle for me – this whole series has taken an extraordinary amount of emotional labor, but this part is particularly challenging. The Antebellum Era, the Civil War, the failures of Reconstruction; it’s fucking heavy.

But we need to remember the past, now more than ever.

One of the primary reasons that the last three articles in this series were so long is because I am going to be drawing on them extensively to help piece this argument together. This is both the longest and the most important essay in this series, and also one of the most undertheorized areas of modern trans studies. I’m going to do my best to earmark the places where I’m referring back to past discussions, but please know that you’ll have the best reading experience here if you’ve already read the last three parts.

Take a deep breath. Here goes nothing.

Peelian Conservatism in the 1820s

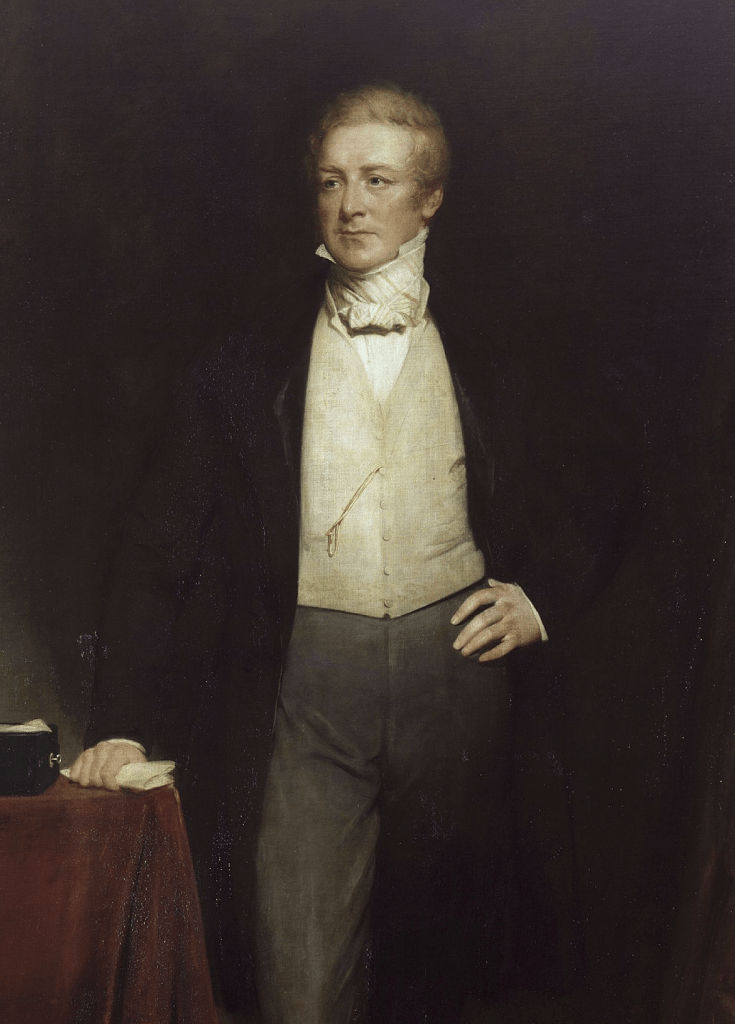

Over the course of this series, I have been introducing you one-by-one to the white men who are responsible for transphobia in the modern world. It brings me absolutely no pleasure to bring us up to the next one, one Sir Robert Peel, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and father of the British Conservative Party. Robert Peel was a contemporary and a political opponent of John Campbell, the man responsible for the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, and he was also a prominent opponent of the Reform Act of 1832 (which Baron Campbell helped to push into law). We discussed both of those laws in Part Two and they will both be relevant in this article, so go back and reread that section on Baron Campbell if you need a refresher.

Let’s cut straight to the chase – Robert Peel essentially invented modern policing, and he is the man who formalized the death penalty for sodomy and buggery in the UK. He was a major actor in many of the policies we discussed in “Trans-Atlantic Relations” from the Whiggish point of view, and thus it now falls upon us to recant them from the perspective of the other side, i.e. the Tories, opponents of abolition and moral reform alike.

In Part Two, we discussed how the first British obscenity statute was passed as part of the Vagrancy Act of 1824, which was created in explicit opposition to French Jacobism and sought to suppress homelessness and crime from refugees in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. As we discussed earlier, William Wilberforce was a staunch opponent of this act, which he saw as too harsh on the homeless. Unfortunately (and still resounding to this day), Wilberforce fell ill right before the vote and wasn’t able to oppose it on the floor. One of the many societies that had sprung up in the model of Wilberforce’s Society for the Suppression of Vice (which would become one of the primary drivers of anti-trans censorship) was the Society for the Suppression of Mendicity, which was supposedly aimed to reform the issue of “begging” but in reality drove a broad wave of criminalization against the poor. Founded in 1818, the Society for the Suppression of Mendicity offered the following objectives in its first publication:

It will be recollected that in the early part of the year 1818, a very powerful impression was made upon the public mind by a sudden and alarming increase in the number of Vagrants in the Metropolis.

Groups of miserable objects, many in the garb of seamen, others in a state nearly approaching to nudity, thronged in our principal streets, or were found, night and day, upon the bridges and in the most frequented parts of the town, presenting an aggregate of human suffering which it was evident no ordinary distribution of alms could hope to mitigate. […]

In addition to this, (and which was of infinite importance) the public attention was by peculiar circumstances excited to a serious consideration of the subject, as connected most intimately with the alarming increase of juvenile crime – with our present system of police; and with the momentous question of the parochial relief of the poor. The period appeared therefore particularly adapted for the establishing in the Metropolis a Society, of a nature similar to those which had been already instituted with success in other parts of the kingdom; and thus was formed the present Institution.2

Here we arrive at what is perhaps the most critical concept in this whole article, that of recuperation. Political recuperation is a process by which the radical and progressive ideas of social movements are warped, co-opted, and ultimately reassimilated into the normative power structures of oppression they initially sought to oppose. The story I want to tell you in this article is a story of how the social progressivism of the Evangelical movement was recuperated over the course of the 19th Century, and it begins here, with a copycat society that (successfully) sought to use the aesthetics of Wilberforcean moral reform to pioneer the contemporary police force.

In 1824, the Society for the Suppression of Mendicity successfully lobbied Sir Robert Peel (who was then Home Secretary) to make the language of the Vagrancy Act significantly harsher. But that was only the preamble to Robert Peel’s influence on the British legal system. Over the next few years, the British Parliament would pass a series of laws known to history as Peel’s Acts, which would standardize and reimagine vast swathes of the British criminal code, including the Offenses Against the Person Act of 1828, which formalized the death penalty for sodomy and buggery as we briefly discussed in Part Two.

At the apex of this historic run of legal reform, Sir Robert Peel would be responsible for the creation of the London Metropolitan Police, which is perhaps his most enduring legacy. He created a set of tenets for modern policing known as the “Peelian Principles,” which are still commonly circulated among police departments to this day. They read as follows:

1. To prevent crime and disorder, as an alternative to their repression by military force and severity of legal punishment.

2. To recognise always that the power of the police to fulfil their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of their existence, actions and behaviour and on their ability to secure and maintain public respect.

3. To recognise always that to secure and maintain the respect and approval of the public means also the securing of the willing co-operation of the public in the task of securing observance of laws.

4. To recognise always that the extent to which the co-operation of the public can be secured diminishes proportionately the necessity of the use of physical force and compulsion for achieving police objectives.

5. To seek and preserve public favour, not by pandering to public opinion; but by constantly demonstrating absolutely impartial service to law, in complete independence of policy, and without regard to the justice or injustice of the substance of individual laws, by ready offering of individual service and friendship to all members of the public without regard to their wealth or social standing, by ready exercise of courtesy and friendly good humour; and by ready offering of individual sacrifice in protecting and preserving life.

6. To use physical force only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient to obtain public co-operation to an extent necessary to secure observance of law or to restore order, and to use only the minimum degree of physical force which is necessary on any particular occasion for achieving a police objective.

7. To maintain at all times a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and that the public are the police, the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

8. To recognise always the need for strict adherence to police-executive functions, and to refrain from even seeming to usurp the powers of the judiciary of avenging individuals or the State, and of authoritatively judging guilt and punishing the guilty.

9. To recognise always that the test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, and not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with them.3

I include the full list of principles here for a couple reasons. It’s important to acknowledge that, on fact, there is a motion toward virtue here, an ideal of civic governance that still animated conservative politics to this day. But the moment you start to dig, the cracks begin to show.

Firstly, Robert Peel’s vision for the Metropolitan Police centers not on upholding the law or promoting justice, but upon the active cultivation of public opinion. In other words, Peelian policing is a police force whose primary objective is the maintenance and reproduction of its own existence. In this theoretical mode, the police are as engaged in propagandism and civil outreach as they are in actual law enforcement – telling, then, that the appearance of “police efficiency” rests in the invisibility of criminality to the public eye, not the actual mechanisms by which the law is enforced.

Secondly, I want to draw your attention to the idea that “the police are the public and the public are the police.” This philosophy draws an explicit boundary between a law-abiding “public” and the law-breaking “vagrant,” producing a direct justification for our modern prison system as a need to keep the “public” and the “vagrant” isolated from each other.

Peel’s vision for accomplishing this should feel darkly prescient for a reader in the 2020s:

Peel believed that the function of the London Metropolitan Police should focus primarily on crime prevention—that is, preventing crime from occurring instead of detecting it after it had occurred. To do this, the police would have to work in a coordinated and centralized manner, provide coverage across large designated beat areas, and also be available to the public both night and day. It was also during this time that preventive patrol first emerged as a way to potentially deter criminal activity. The idea was that citizens would think twice about committing crimes if they noticed a strong police presence in their community. This approach to policing would be vastly different from the early watch groups that patrolled the streets in

an unorganized and erratic manner. Watch groups prior to the creation of the London Metropolitan Police were not viewed as an effective or legitimate source of protection by the public.It was important to Sir Robert Peel that the newly created London Metropolitan Police Department be viewed as a legitimate organization in the eyes of the public, unlike the earlier watch groups. To facilitate this legitimation, Peel identified several principles that he believed would lead to credibility with citizens including that the police must be under government control, have a military-like organizational structure, and have a central headquarters that was located in an area that was easily accessible to the public.4

What I want to underscore here – apart from the obvious similarities between Peel’s London police and the police state in modern America – is that modern policing came about in direct tandem with the formalization of common law into strict misdemeanor codes that defined legality and criminality down to the smallest act. If you recall back to Part One of this series, many of the anti-obscenity laws we discussed came in the form of vague royal decrees. They were not statutes, they were edicts – but that’s exactly the impact men like Robert Peel had on Western governance during the 19th Century.

British Reform and the Tamworth Manifesto

Despite the sweeping expansion of the regulatory state by Tory leadership during this era, the British population was growing increasingly vocal in support of reform. In 1830, the Tories lost power and a Whig government was installed; and within a few short years, that new government had passed both the Reform Act of 1832 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, all while Robert Peel vocally stood as the opposition leader in their stead.

The seismic impacts of this moment in British political history would be felt across both sides of the Atlantic. Before we cross the pond, we need to linger on Robert Peel’s political thought as this period of reform came to a close (Wilberforce was dead, slavery was nominally abolished) and the Tories came back into power, shaken by how much the Whigs had managed to change in such a short time.

Robert Peel’s opposition to the Reform Act is very illustrative in this regard. Historian of the bill Antonia Fraser recounts:

Lamentably, Peel saw principles in operation which he believed would be fatal to ‘the well-being of society’. Whenever the Government showed signs of resisting those principles, he would give them his support; conversely, when the Government encouraged them, he would offer ‘his decided opposition’. Unlike the Duke of Wellington, Peel was careful not to set his face publicly against all change: he was in favour of reforming every institution that really required it, but he preferred to do so ‘gradually, dispassionately, and deliberately’ in order that Reform might be long-lasting. Peel was setting the tone for an Opposition which took its stand on integrity and tradition, not on a mulish determination to cause havoc.5

And so a tale of two “reforms” begins to emerge. On one side, we have the dramatic abolitionism and electoral reform of the Whigs, which entirely reshaped the political map of Britain, and on the other side, we have the Tories, who strongly believe in gradual change (i.e. gradualism, that pesky ideology that slavery ought to be banned, but ‘not yet’) to be engineered and carried out in the fine print of the law, through lengthy penal codes and militarized citizen police forces to enforce them in the streets.

Starting to sound familiar?

As we extensively discussed in Part Three of this series, the American Whig Party never did anything that could remotely be described as “dramatic abolitionism and electoral reform.” While there were limited progressive factions who might have preferred such outcomes, most American Whigs had vested interests in slavery, gerrymandering, and the Electoral College, and had absolutely no such designs in mind.

However.

To a frightened Southern planter class with tightly wound economic ties to the British Crown, the optics of a liberal Whig Party banning slavery and rewriting the political map to remove Conservative districts was nothing short of a night terror. The brief reign of the British Whigs between 1830 and 1834 was more than enough to stoke fears of a repeat performance by their American counterparts.

A fully emboldened American Whig Party taking power and attempting the same in the States was nothing short of unacceptable.

As he returned to power as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in December of 1834, Robert Peel published a document known as the Tamworth Manifesto, which contained a new philosophy of conservatism that would reverberate far beyond the halls of Parliament. I open this article with Peel’s political philosophy because understanding the prominent conservative philosophy of this era will be crucial to understanding why and how cross-dressing was criminalized in the manner that it was.

Recuperation. The Reform Act had been passed, slavery had been abolished. Sir Robert Peel knew that there would be no return to the prior situation of the Tories, and so he instead declared his support for the change:

Now I say at once that I will not accept power on the condition of declaring myself an apostate from the principles on which I have heretofore acted. At the same time, I never will admit that I have been, either before or after the Reform Bill, the defender of abuses, or the enemy of judicious reforms. I appeal with confidence in denial of the charge, to the active part I took in the great question of the currency – in the consolidation and amendment of the Criminal Law – in the revisal of the whole system of Trial by Jury – to the opinions I have professed, and uniformly acted on, with regard to other branches of the jurisprudence of this country – I appeal to this as a proof that I have not been disposed to acquiesce in acknowledged evils, either from the mere superstitious reverence for ancient usages, or from the dread of labour or responsibility in the application of a remedy.

But the Reform Bill, it is said, constitutes a new era, and it is the duty of a Minister to declare explicitly – first, whether he will maintain the Bill itself, secondly whether he will act on the spirit in which it was conceived.

With respect to the Reform Bill itself, I will repeat now the declaration I made when I entered the House of Commons as a member of the Reformed Parliament – that I consider the Reform Bill a final and irrevocable settlement of a great constitutional question – a settlement which no friend to the peace and welfare of this country would attempt to disturb, either by direct or by insidious means.

Then, as to the spirit of the Reform Bill, and the willingness to adopt and enforce it as a rule of government: if, by adopting the spirit of the Reform Bill, it be meant that we are to live in a perpetual vortex of agitation; that public men can only support themselves in public estimation by adopting every popular impression of the day, – by promising the instant redress of anything which anybody may call an abuse – by abandoning altogether that great aid of government – more powerful than either law or reason – the respect for ancient rights, and the deference to prescriptive authority; if this be the spirit of the Reform Bill, I will not undertake to adopt it. But if the spirit of the Reform Bill implies merely a careful review of institutions, civil and ecclesiastical, undertaken in a friendly temper combining, with the firm maintenance of established rights, the correction of proved abuses and the redress of real grievances, – in that case, I can for myself and colleagues undertake to act in such a spirit and with such intentions.6

This is classic conservative snake oil, but it’s crucial to recognize that at this moment in political history, the London Metropolitan Police was a radical and untested source of authority. Robert Peel believed in it, to be certain, but history had yet to make much of its novelty. Peel could credibly claim to support government reform because he had reformed the criminal justice system, he had reformed municipal order in one of the biggest cities in the world.

By nominally endorsing Reformism in his new government, Robert Peel was able to position his legislative vision for the modern city at the very heart of the burgeoning Reform movement. Just as the Peelian Principles mandated, Peel’s Tory government did not stand in opposition to the people’s desire for change, but rather sought to harness and redirect it toward projects like the Metropolitan Police, which seemed on face a continuation of Reformist policies but in actuality would move the nation into a far deeper conservatism than before (this was, after all, a prelude to the notoriously conservative and prudish Victorian and Edwardian eras).

If this tactic sounds familiar, it’s because it’s the exact same thing that right-leaning politicians around the world are doing with trans issues over 190 years later.

The police, misdemeanor codes, and Peelian Conservatism are some of the most successful Trojan horse tactics in the history of modern politics, and the history of anti-trans censorship is a shining example of how they have been deployed in the United Kingdom and the United States alike to grim effect.

The Birth of Fascist Censorship in the Deep South

How Slave Revolts Shaped the Antebellum

The chain of dominos that would eventually lead the city of St. Louis to make both cross-dressing and possessing obscene literature a formal misdemeanor began with slave revolts, as so many things in the 19th Century did.

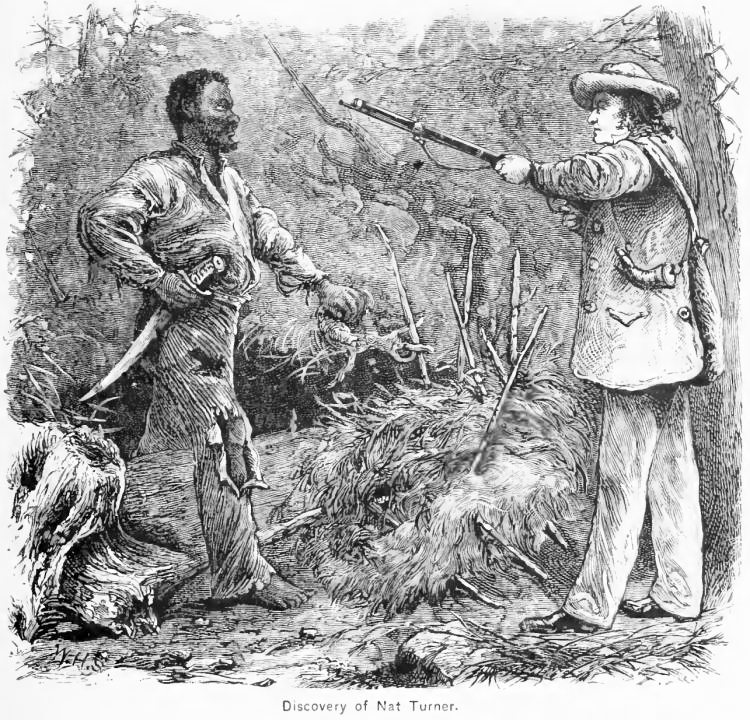

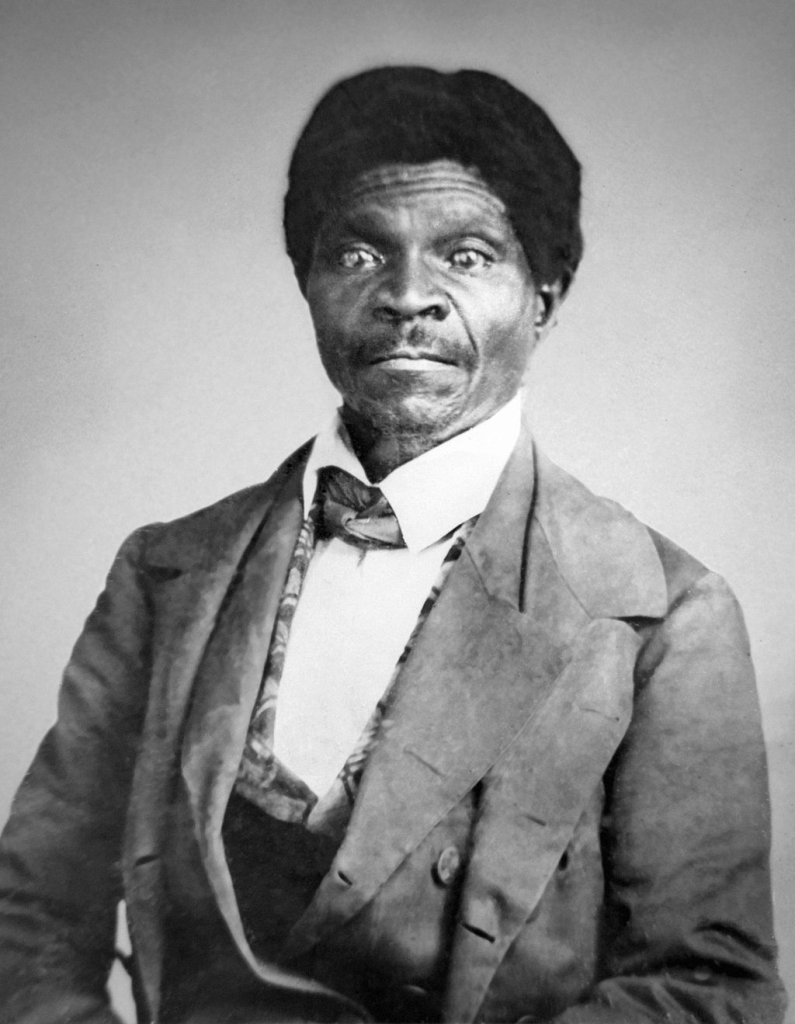

Two slave revolts – one in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1822 [Denmark Vesey] and the other in Southampton, Virginia, in 1831 [Nat Turner] – had triggered a war on Black literacy that eventually engulfed the entire South. The revolt leaders were highly literate and leveraged the knowledge and communication ability that literacy provided to catalyze their followers. Between the revolts, a third Black man – free and living in the North – had written a manifesto and started shipping it into the depths of slavery’s empire. He called on Black people, free and enslaved, to shake off the mental chains of slavery through education and seize freedom as their birthright by any means necessary.7

The history of anti-literacy campaigns against the Black population in the South is an enormously complicated topic, and it’s been covered admirably in the book by Derek W. Black I just cited, entitled Dangerous Learning: The South’s Long War on Black Literary. It’s an excellent piece of scholarship and I highly recommend you go and read it for yourselves. I’m gonna be quoting mostly from the introduction to give you a broad overview, but there’s a lot of textural nuance here that I simply don’t have time to cover in this article.

The manifesto that Black references in this passage is “An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World” by David Walker, first published in 1829. Rather than attempting to trace out the criminalization of Black literacy during the 1820s, I find it instructive to hear it directly from the primary source:

It is a fact, that in our Southern and Western States, there are millions who hold us in chains or in slavery, whose greatest object and glory, is centered in keeping us sunk in the most profound ignorance and stupidity, to make us work without remunerations for our services. Many of whom if they catch a coloured person, whom they hold in unjust ignorance, slavery and degradation, to them and their children, with a book in his hand, will beat him nearly to death. I heard a wretch in the state of North Carolina said, that if any man would teach a black person whom he held in slavery, to spell, read or write, he would prosecute him to the very extent of the law.—Said the ignorant wretch,* “a Nigar, ought not to have any more sense than enough to work for his master.” May I not ask to fatten the wretch and his family ?

These and similar cruelties these Christians have been for hundreds of years inflicting on our fathers and us in the dark, God has however, very recently published some of their secret crimes on the house top, that the world may gaze on their Christianity and see of what kind it is composed.

Georgia for instance, God has completely shown to the world, the Christianity among its white inhabitants. A law has recently passed the Legislature of this republican State (Georgia) prohib-

iting all free or slave persons of colour, from learning to read or write; another law has passed the republican House of Delegates, (but not the Senate) in Virginia, to prohibit all persons of colour, (free and slave) from learning to read or write, and even to hinder them from meeting together in order to worship our Maker ! ! ! ! ! !Now I solemly appeal, to the most skilful historians in the world, and all those who are mostly acquainted with the histories of the Antideluvians and of Sodom and Gomorrah, to show me a parallel of barbarity. Christians ! ! Christians ! ! ! I dare you to show me a parallel of cruelties in the annals of Heathens or of Devils, with those of Ohio, Virginia and of Georgia—know the world that these things were before done in the dark, or in a corner under a garb of humanity and religion.8

I didn’t know this pamphlet existed before I began the research for this article, and wow – it’s a lightning rod. Go and check it out yourself.

Given how the early parts of this series have been jumping back and forth across oceans and chronologies, I believe that it’s important to take a moment to signpost the order in which all these important events took place. At the same time that the Tories were passing sweeping criminal reform in the 1820s, the South was passing stringent laws to control Black speech, movement, and literacy, imposing harsher and harsher penalties against anyone who might seek to overturn slavery’s reign. Walker’s Appeal was published in 1829, the same year that Robert Peel created the London Metropolitan Police.

By 1831, the Reformist movement in the UK had taken full steam, and the Whig Party had already begun to drive hard toward the passage of the bill. By the time Nat Turner revolted that winter, its passage had become a distinct possibility. Within the two year period after Nat Turner’s revolt, the British passed both the Reform Act of 1832 to strip several conservative politicians of the seats and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 to permanently outlaw British slavery.

In this charged political moment where the promise of abolition suddenly seemed not just possible, but likely, the American Anti-Slavery Association was founded in December of 1833 with the explicit intent of reproducing British abolition in the United States. By the time the Tories resumed power in late 1834 with Sir Robert Peel as the Prime Minister, the AA-SS had already embarked upon their grand pamphlet campaign – the one which sparked the panic in the Jackson administration that we previously discussed.

While I am doing my best not to repeat what has already been said in this series, I think it’s important to remember that Andrew Jackson and his Democratic proponents, specifically John C. Calhoun, the Southern Democrat member of the Great Triumvirate we discussed the least of the three, were explicitly leery of the idea of using the federal government to censor abolitionist publishing, on the rationale that the same power could easily be deployed by a Whig government to promote an anti-slavery agenda.

No – another path forward needed to be created, a path that would mandate the power of Southern slave states, irrespective of who occupied the White House.

The 1835 Postal Controversy and Censorship-by-Mail

We return to Black’s account in the wake of Nat Turner’s 1831 revolt, the prelude to all of this abolitionist activity:

Hysteria ensued across the South. White leaders were convinced that Black literacy was to blame for the rebellions and that the manifesto would provoke more. Literacy alerted Black people to Congress’s slavery debates, sparked notions of revolution, inflated their expectations of a better way of life, and exposed them to contradictory biblical passages that, in white Southerner’s view, would overwhelm their capacity to understand. The only safe course of action was to keep dangerous information secret.

By the early 1830s, all but a few Southern states had imposed severe sanctions on any enslaved person caught trying to read or write, as well as on any person, white or Black, caught teaching them. Some states went further, criminalizing literacy for free Black people, too. The punishment for a first offense was fifty lashes. For the second, in some states, it was death. […]

The hysteria extended to books and newspapers, too. Even for white people, it was a crime to possess certain texts. At first, abolitionist newspapers were banned. But once abolitionist literature was expunged, governments in the South looked for new villains. Some leaders claimed that all Northern literature, including its magazines and textbooks, was infected with anti-Southern bias that would undermine the Southern way of life. As a replacement, they pushed textbooks and literature from the South, by the South, and for the South. By the mid-1830s, a pall of orthodoxy had descended over the region, constricting not only Black people’s literacy but white people’s access to information. The orthodoxy only grew more belligerent, more unpersuadable, and more repressive with time.10

By the time the AA-SS’s pamphlet campaign sparked the postal kerfuffle of 1835, the South had already worked itself up to a fever pitch on the issue of abolitionist publishing and incendiary literatures. It is at this turning point in our history that we receive this critical account of the events of 1835 from historian Susan Wyly-Jones:

The wave of anti-abolition meetings that swept across the South in the fall of 1835 provides several important insights into the beliefs and strategies of Southerners as they confronted the emergence of an activist antislavery movement. First, the meetings highlighted the importance to the region of enforcing community consensus and solidarity on the issue of slavery. Like an insurrection scare, the postal campaign spurred white Southerners to come together in a ritualistic display of racial unity and dedicate themselves to the defense of slavery. The emphasis in the meetings on unanimity, nonpartisanship, and collective action reflected the importance of mobilizing all members of the community behind Southern institutions. The assertion that abolitionists sought to “deluge the land in blood” provided a potent rallying cry to all white Southerners, regardless of their personal interest in slavery, as well as a useful rationalization for the suppression of antislavery publications and the use of violence to defend their communities. Rather than flushing out Southern moderates, as the abolitionists had hoped, the postal campaign pushed opinion more decisively toward a defiant public defense of the South’s domestic institutions.

The meetings also demonstrated the evolution of a constitutionalism, distinctly Southern and proslavery, that established slaveholder interests as the dominant policy positions in Federal and interstate matters concerning slavery. Before the 1830s, Southern thinkers had been preoccupied with checking the “consolidationist” tendencies of the Federal government toward slavery, but the postal campaign of the AAS forced Southerners to reckon with a new enemy. In 1835, this bold, new threat led them to demand noninterference not only from other governing bodies, but also from private citizens, and to broaden the definition of interference to include private speech as well as legislative action. Of course, Southerners had been arguing for decades that slavery was exclusively a local institution over which the Southern states alone had jurisdiction. But the arguments they reached for in 1835 were not purely in the vein of states rights doctrine. Instead, they illustrate a point made long ago by historian Arthur Bestor about the crisis over slavery in the territories–Southern notions about state sovereignty verged toward the consolidation, not the decentralization of power, and were used not to protect but to override individual rights. (42) On the one hand, Southerners who purged antislavery literature from the mails claimed that their own laws, in addition to the “higher law” of self-preservation, trumped the dictates of Federal statutes and the civil liberties enshrined in the Constitution. States rights, in this case, meant the right to dismiss Federal law regarding the rights of citizens of other states. On the other hand, Southerners argued that the “fraternal bonds of Union” obliged Northern states not merely to mob abolitionists out of existence but to suppress them legally. In this argument, comity and Northern deference to Southern law, not the duty of Northern states to protect the rights of their own citizens, reigned supreme. This Machiavellian tendency to disregard state rights and individual liberties when they conflicted with proslavery political strategies appeared repeatedly over the next two-and-a-half decades in such incidents as the successful Southern effort to impose a gag rule on abolition petitions to Congress, John C. Calhoun’s sweeping Senate resolutions in 1837 which argued that Congress had a duty to protect slavery from its critics, and Southern calls in the 1850s for a congressional slave code for the territories.11

There are a couple of really important points I need you to take away from this long passage. Firstly – and if you know what the Comstock Act of 1873 is, you’ll understand why this matters – the Postal Service of the United States was an explicitly White supremacist institution during this period of American history. Often operating in direct opposition to the law, members of the Postal Service systematically sought to control and censor the flow of information in and out of the American South. They did this with the tacit consent of both political parties, as Northern Whigs also believed that abolitionists had no business in trying to spread their persnickety ideas southwards. The USPS did this in the explicit support of Southern slavery and the soft power of the planter class. Keep that in mind.

Secondly, censorship law in the United States, much like in Britain with King George’s various proclamations against seditious speech, has always begun as a direct response to insurrectionism. Moreover, it is assuredly a deeply American fact that those insurrections always, always had to do with slavery and the ownership and control of the Black body. In the United States, which rose up against the British in no small measure to protect the right to own slaves, insurrection is and always has been a racially coded action. A noble act for the white man, savagery for the Indian or the Black man – so the sentiment went. In Part Two, we discussed how the entire project of American independence was structured around the colonization of Haudenosaunee land. Here’s where I begin to tip my hand – I have spent this much time laying out the histories of Black and Indian resistance during this period because both played a direct role in the formulation of American cross-dressing bans.

Thirdly, and this is perhaps the most crucial bit of information here, is the fact that the South figured their new adversary as the private citizen, and her primary weapon against slavery as private speech, constitutionally protected under the First Amendment from prosecution by the federal government. This shift in the States’ Rights doctrine is absolutely crucial to understanding the politics of the 1840s vis a vis the criminalization of trans life. The battle against abolitionist speech had to be waged on the level of the state, yes, but there was the troublesome issue of Northern interference with Southern affairs.

What emerges here is a distinct separation between the legislative developments on the state level between Northern and Southern states over the course of the 1830s, 40s, and 50s. This locality is critical to understand why anti-trans law emerged where it did. In the South, where a combination of White unity and federal complicity gave the Democrats leeway to do whatever they wanted, a severe authoritarianism would emerge that would form the blueprint for the proto-fascist nation of the Confederate States of America. This was an exercise of direct power on the level of the state government, where the South had already begun to essentially operate as its own enclave state.

This was insufficient for the planter class, though. So long as abolitionist sentiments continued to fester in the North, there would always be the danger of another slave revolt, another incendiary pamphlet, another federal attempt to outlaw slavery for good. There was the danger of the Whig Party and the possibility that they might try to follow in the British footsteps of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. And using the federal government to that end was also out of the question – that would give too much possibility of power to the Whigs.

No, the suppression of abolitionist speech in the North would need to be a soft power campaign to sway the popular opinion in the North against the abolitionist movement.

If only there were a hot new right-wing ideology specifically designed to police private citizens while justifying and maintaining its existence in the court of public opinion and codifying a recuperated new system of criminal ‘reform’ (that mythical idea so beloved by the liberal Whigs) into law…

Let’s put it in plain speech – this “Law of Self-Preservation” that the South cites in their turn toward authoritarianism that culminated in 1835 is strongly reminiscent of the verbiage of self-preservation Sir Robert Peel cites in his principles of policing, as well as the language of the Tamworth Manifesto. But the South had no need of a “Metropolitan Police” department, because the dividing line between the “public” and the “vagrant” was as clear and self-evident as the color of your skin. Every White man was an officer, every White woman an informant, every Black man a criminal, every Black woman an accessory to his crimes.

THE POLICE ARE THE PUBLIC

THE PUBLIC ARE THE POLICE

The Confederate States of America was the world’s first police state, the world’s first fascist state, and it began not when the shots were first fired at Fort Sumter, but when the Southern block began to actively violate federal law through the censorship of the post.

Deportation and Ethnic Cleansing in 1830s Missouri

A Quick Tour of the Show-Me State

Oh, god. Missouri.

Fucking Missouri. How can I describe to you, my dearest reader, the sheer depths of my loathing for the state of Missouri?

For the next section of this article, the physical geography of the states of Missouri and Illinois is going to become reasonably important. I know that there’s a lot of non-Americans reading this, so I hope that my American audience will excuse me for a moment to give folks a quick geography primer on one of the most obscure states in America.

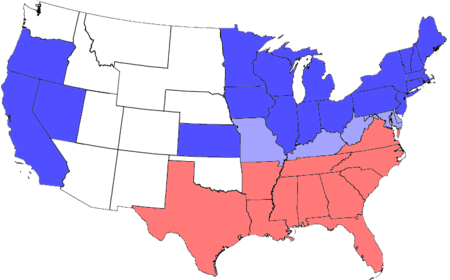

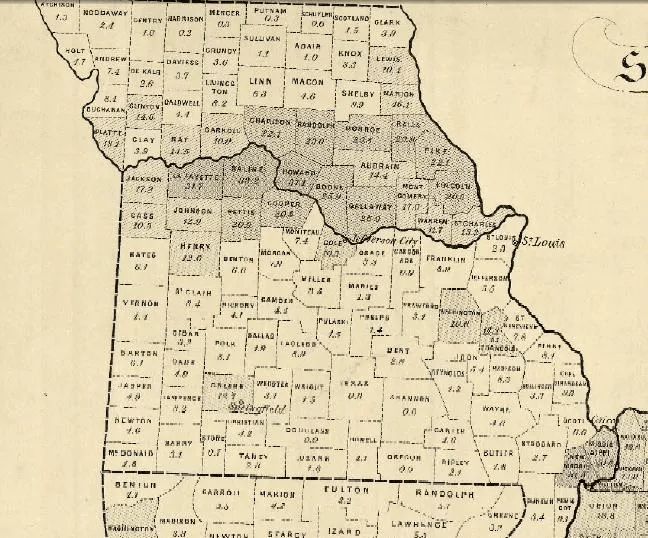

Firstly, for those unaware, during the American Civil War (1861-1865), not every state in the Union had abolished slavery. There were four states that remained with the Union despite continuing to allow slavery: from East to West, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. The East-West axis also predicts how much the states wanted to secede; Delaware never even tried, while Missouri had rival governments until the Union consolidated power in 1862. A fifth “border” state, West Virginia, was created in 1863 out of territory captured from the Confederacy. Here is a political map of the (extremely not) United States in 1863:

Missouri is the state in light blue at the left-most edge of the border region.

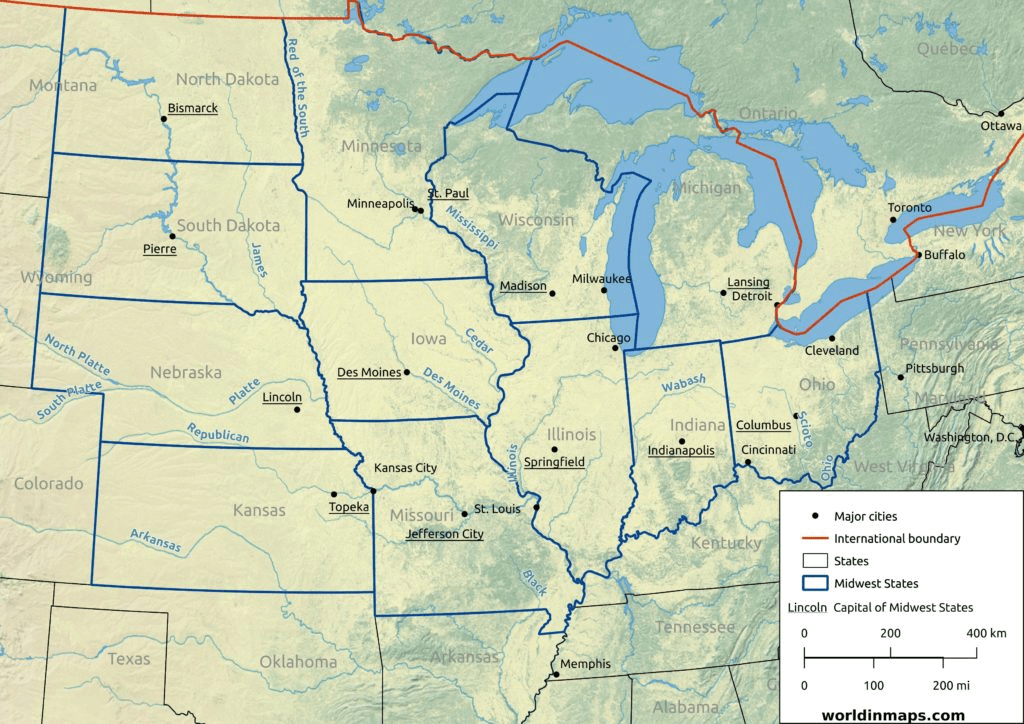

For those who are not used to the fuckery of American geography, you may notice that Missouri’s northern and southern borders are both straight lines, while its eastern and western borders are both squiggly. Let’s zoom the map in a little bit.

Our primary concern right now is with the band of four states in the middle of the map: Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. We will also be discussing Kentucky, which borders all four of them to the south, and Tennessee, which is south of Kentucky below that.

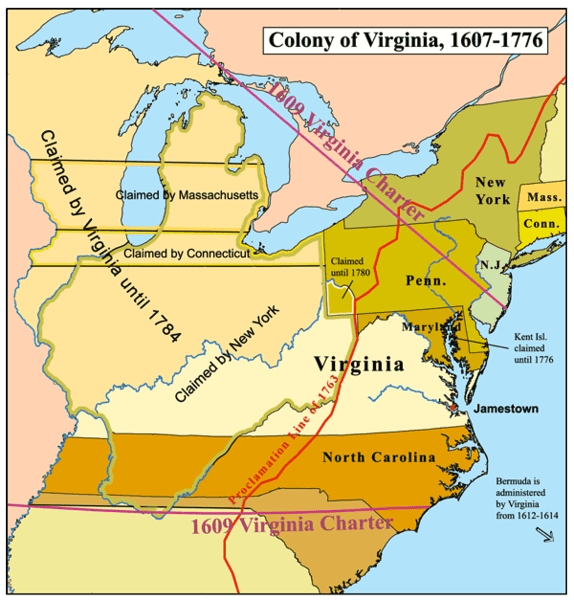

Missouri’s borders are dictated by the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which we discussed at the beginning of Part Three of this series. The entire point of the Compromise, the literal sole reason that Missouri exists in the state that it does, was for the preservation of slavery. In the Senate of the United States, each state has two Senators regardless of the size of its population – a system of governance invented by Virginia during the Constitutional Convention to protect the interests of white Southern slaveholders against the “tyranny” of a northern majority.

The Missouri Compromise follows the colonial boundaries between the colonies of Virginia and Carolina, which if you’ve ever seen a map of colonial North America, the British would determine borders at the coast then extend that shit all the way to the other side of the map. Manifest Destiny began when white men took a ruler to a map and declared the entire West their property. As we discussed in Part Two, much of the colonial conflict between the UK, France, Haudenosaunee, and what would become the US was a contest over that imagined endless Western parallel, and the right to expand beyond the Mississippi River.

Missouri was not a state – Missouri was an ideal. If you look at a map of the United States in 1820, almost half of the damn country is labeled as “Missouri Territory.” “Missouri” was the entire Louisiana Purchase north of Arkansas, and then some. Missouri was the project of American imperialism in its most literalized terms.

Why is this state Missouri, then, and not the rest of the region? With the complicated exception of Louisiana, which has its own history, Missouri was the first state created to the west of the Mississippi River, the first state to be made out of the formerly French territory bought by Thomas Jefferson. It was the site of a fierce struggle about the soul of a nation, and the Missouri Compromise that created it is a damning picture of that country.

The Mississippi River to the East. The Missouri River to the West. From north to south, Missouri is bordered by the two longest rivers in North America, rivers which span directly from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada.

Missouri’s straight northern border is fashioned after the Mason-Dixon line that divides Pennsylvania and Maryland, also a border between slave states and free states. Missouri’s straight southern border was thus negotiated to be the new free-slave border that all future states would be evaluated by.

In a very literal sense, the geography of Missouri is like a perfect Venn diagram of the United States. It has the slave parts of the North and the slave parts of the South; it has a gateway to the entire pre-Louisiana Purchase nation and remains the open transverse upon which this country built its expansion west.

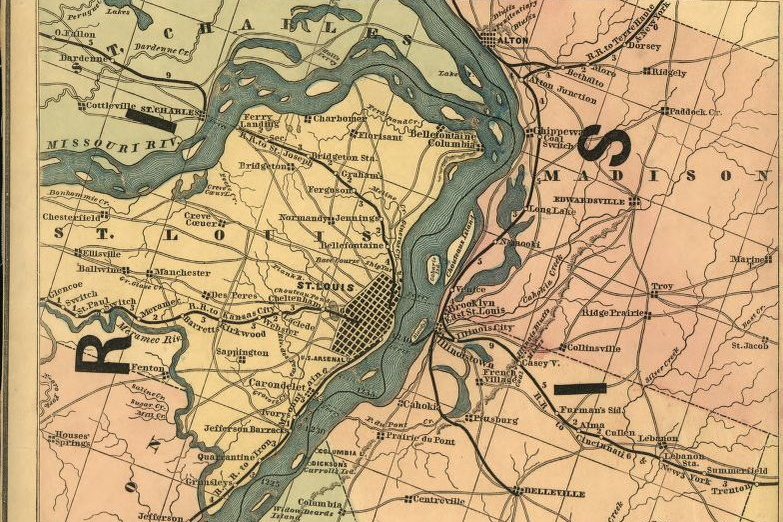

Crucially, Missouri’s biggest city lies right on its eastern border, right at the the transitional point from free to slave, from east to west, from north to south. At this point in American history, St. Louis is the midpoint of American political geography.

Let’s zoom in again.

St. Louis has some of the most ridiculous geography of any city on the planet. On the map to the left, you can see that the Mississippi runs up the full eastern border of Missouri, whereas the Missouri river runs down the upper part of the Western border before cutting across the state to join the Mississippi. The city of St. Louis is built at the junction point of the two largest rivers in North America.

I want you also to pay close attention to the map on the left – the counties with darker shading are counties which had a higher density of enslaved people. As you can see, slavery in Missouri was not concentrated in the Southern part of the state as one might expect, but rather along the east-west transverse of the fertile Missouri River plains. Why? The entire southern half of Missouri is part of a region known as the Ozarks, which can be difficult to traverse and farm, and to this day is still one of the less-dense areas of that part of the country.

The Missouri Compromise was a coup for Southern slaveholders because the real value of Missouri was in its Northern half, not its Southern half. A Missouri without the Missouri River Valley would have been useless to the plantation owners.

Indian Removal and the Ethnic Cleansing of the Sauk People

There was, however, a major problem for the budding proto-fascist Confederacy, and that was that the entirety of that fertile Northern slave-friendly heartland only had one singular point of access, and that was along the very, very long span of the Mississippi River that ran between the impassable Ozarks and the deep-blue state of Illinois. If you wanted to ship human chattel from Mississippi to Missouri, the only way that you could do so both legally and efficiently was on the Mississippi River, and all traffic to the Missouri River and the returned security of deep slave country was forced to run through the city of St. Louis.

You can see the free country of Illinois from the docks of St. Louis, which meant that any slave in the city knew that if they could just find a way to swim or sneak across, they had freedom within palm’s reach.

For slaveholders in Missouri, that was an unacceptable state of affairs.

Missouri was the site of human traffic in both senses of the term for the entire 19th Century, but the 1830s were a particularly busy time for the Show-Me State (a nickname which comes from the fact that Missouri was one of the first states to demand train passengers show their tickets on entry). The flow of bodies in and out of the state was not an auxiliary concern – it was the primary issue of both Missouri’s state government and the city of St. Louis, and so much of the history I’m about to share with you reflects that.

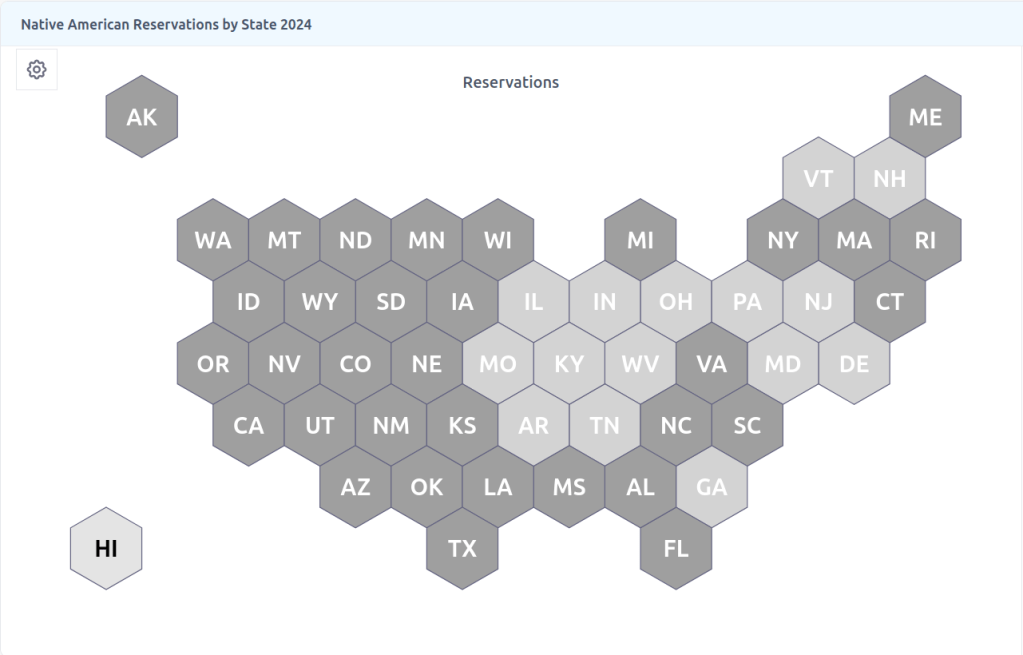

The first group of trafficked peoples relevant to our history are the indigenous peoples of Missouri, namely Thâkîwaki (the Sac and Fox Tribe in English), the group that inhabited the northern parts of the state. One of the uniting factors that binds together the six states in our immediate inquiry is that none of them have Native American reservations – which means that during the genocides of the 19th Century, the entire Native populations of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee were either killed or forcibly relocated to another state.

Here’s an instructive map of American states by which ones have Native reservations and which ones don’t:

That big blob of states in the middle of the country with zero Native reservations? That’s where the American cross-dressing ban was born.

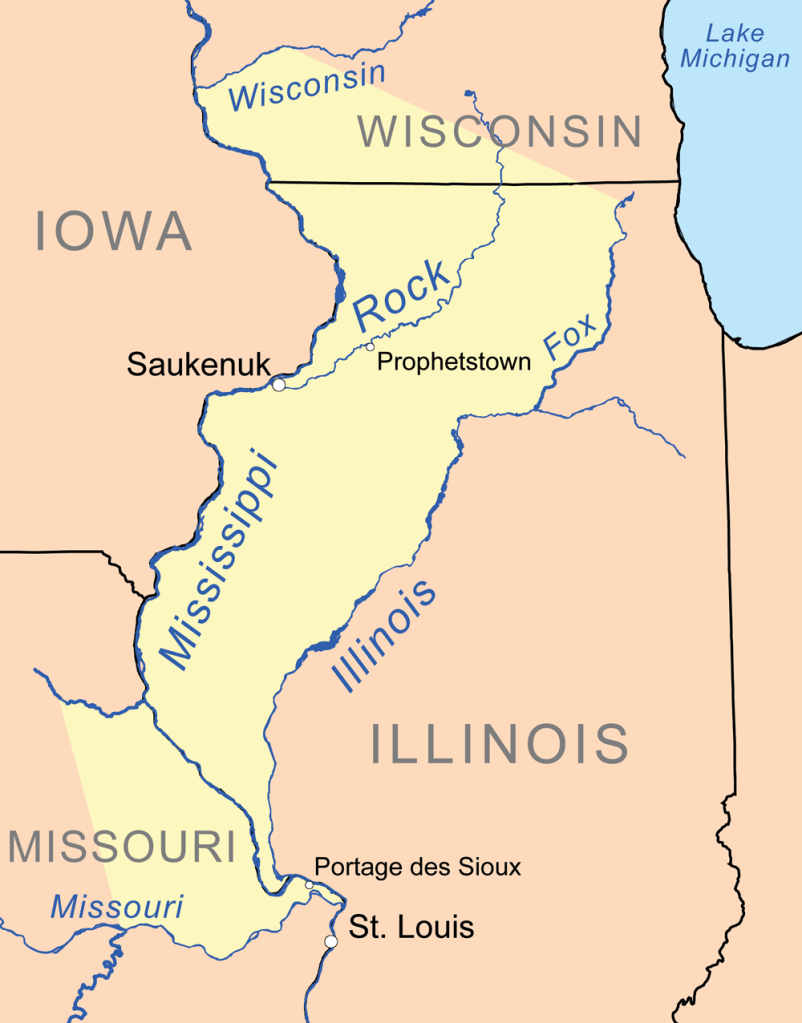

The critical legal document of note here is the 1804 Treaty of St. Louis, which officially ceded Northern Missouri from the Sac and Fox Tribe to the US government, including the vast majority of what would become Missouri’s slavery heartland. It’s really striking how much the Missouri part of this map lines up against the slavery density map I showed you earlier. Throughout this series, we have been discussing how the boundaries of indigenous lands have informed the transverses of American politics long after those indigenous peoples had been killed or displaced, and the land cessation from the Treaty of St. Louis is absolutely no exception.

We will be talking extensively about how the political relationship between the St. Louis region and Western Illinois informed the modern shape of cross-dressing bans, and I don’t want you to forget for a second that these two regions were one nation for most of North American history, arbitrarily divided by a white man’s lines on the map.

For a first hand account of the signing of this treaty, we turn to the autobiography of Black Hawk, a leader of the Sauk who had not authorized its signing:

Quashquame, Pashepaho, Ouchequaka and Hashequarhiqua were sent by the Sacs to St. Louis to try and free a prisoner who had killed an American. The Sac tradition was to see if the Americans would release their friend. They were willing to pay for the person killed, thus covering the blood and satisfying the relations of the murdered man.

Upon return Quashquame and party came up and gave us the following account of their mission:

On our arrival at St. Louis we met our American father and explained to him our business, urging the release of our friend. The American chief told us he wanted land. We agreed to give him some on the west side of the Mississippi, likewise more on the Illinois side opposite Jeffreon. When the business was all arranged we expected to have our friend released to come home with us. About the time we were ready to start our brother was let out of the prison. He started and ran a short distance when he was SHOT DEAD!

This was all they could remember of what had been said and done. It subsequently appeared that they had been drunk the greater part of the time while at St. Louis.

This was all myself and nation knew of the treaty of 1804. It has since been explained to me. I found by that treaty, that all of the country east of the Mississippi, and south of Jeffreon was ceded to the United States for one thousand dollars a year. I will leave it to the people of the United States to say whether our nation was properly represented in this treaty? Or whether we received a fair compensation for the extent of country ceded by these four individuals?18

I hardly think I would be alone in saying that this was anything but a fair deal – but I know for a fact that the future state of Missouri would beg to disagree.

The 1804 treaty ceded the Northeastern part of the state, but the Western half of the state would not be ceded until an 1824 treaty with the Iowa people (four years after Missouri statehood) that surrendered the rest of the land. For a taste of that treaty:

THE Ioway Tribe or Nation of Indians by their deputies, Ma-hos-kah, (or White Cloud,) and Mah-ne-hah-nah, (or Great Walker,) in Council assembled, do hereby agree, in consideration of a certain sum of money, &c. to be paid to the said Ioway Tribe, by the government of the United States, as hereinafter stipulated, to cede and forever, quit claim, and do, in behalf of their said Tribe, hereby cede, relinquish, and forever quit claim, unto the United States, all right, title, interest, and claim, to the lands which the said Ioway Tribe have, or claim, within the State of Missouri, and situated between the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and a line running from the Missouri, at the mouth or entrance of Kanzas river, north one hundred miles, to the northwest corner of the limits of the state of Missouri, and, from thence, east to the Mississippi.

It is hereby stipulated and agreed, on the part of the United States, as a full compensation for the claims and lands ceded by the Ioway Tribe in the preceding article, there shall be paid to the said Ioway tribe, within the present year, in cash or merchandise, the amount of five hundred dollars, and the United States do further agree to pay to the Ioway Tribe, five hundred dollars, annually, for the term of ten succeeding years. […]

The undersigned Chiefs, for themselves, and all parts of the Ioway tribe, do acknowledge themselves and the said Ioway Tribe, to be under the protection of the United States of America, and of no other sovereign whatsoever; and they also stipulate, that the said Ioway tribe will not hold any treaty with any foreign powers, individual state, or with individuals of any state.19

Yes, you read that correctly – the 1824 treaty gave the US Government more land for less money over two decades later.

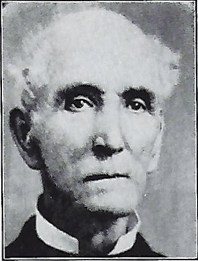

These treaties were terrible deals for the Native peoples of Missouri, and they provided the necessary pretext for the complete ethnic cleansing and displacement of the entire Native population of the state. As the Indigenous tribes of the region grew increasingly privy to the genocidal intentions of the United States, they began to resist more stringently, and in 1829 launched an armed insurrection known as the Big Neck War after their leader Moanahonga AKA Big Neck, pictured left. Though the revolt was quickly squashed by the state militias of Missouri and its leaders were acquitted of wrongdoing (a fortunate result given how these things often went), it left a psychological unease on the psyche of the colonizers of Northern Missouri, who had grown increasingly paranoid at the possibility of Native and slave revolt alike.

Freedom Licenses and Anti-Black Surveilance

The Show-Me State began to earn its nickname in 1835, where it began to pioneer a first-of-its-kind program to police the movement of Black bodies with the innovation of the “freedom license.” Freedom licenses were a uniquely Northern form of institutionalized slavery – they required that any freedman in the state of Missouri had to carry around official documentation of their free status in order to reside in the state, and to be prepared to show it to a white inspector at any moment. Ebony Jenkins writes about the law:

On March 14, 1835 the General Assembly of the State of Missouri passed “An act concerning free negroes and mulattoes”. The act stated that all free persons of color had to apply for a freedom license. The courts could, if they chose, grant a license to “any free negro or mulatto, possessing the qualifications required by this act to reside within the state”. The act was another hurdle that African Americans living in Missouri had to overcome. Not only did they have to go to the court and possess the qualifications to apply for a freedom license, but the applicant also had to be either born in Missouri or prove that they “were residents of this state on the seventh day of January, in the year eighteen hundred and twenty-five, and continue to be such residents at the taking effect of this act” and “produce satisfactory evidence that he is of the class of persons who may obtain such license, that he is of good character and behavior, and capable of supporting himself by lawful employment, [that] the court may grant him a license to reside with the state”21

“An act concerning free negroes and mulattoes” is one of the more evil pieces of legislation I have had the displeasure of reading for this project, and let me tell you, it’s worse than it appears on face. Firstly, this bill essentially regulates that an enslaved Black person from the South could not be freed in the state of Missouri if they were trafficked north after its passage, as they could not legally receive a freedom license. Missouri’s freedom license program is one of the earliest models for deportation in the United States – starting in 1835, there would be a steady stream of state removals of free Black bodies from the state, aimed with the ultimate goal of creating a society where there would only be Black slaves in the borders of the state. Missouri’s deportation programs during this period are, in many ways, early shadows in American history of the future institution of ICE.

Secondly, the provisions that free Blacks needed to have “class” and “good character and behavior” were the early legal pretexts for Missouri to begin experimenting with Peelian conservatism in the state. By creating a legitimate interest for the government to be policing the actions of private citizens – checking Black people for freedom licenses – Missouri had artificially begun to create the need for an administrative force that could adequately patrol and surveil the movement and possessions of Black Missourians, especially those in St. Louis who stood dangerously close to the free banks of Illinois.

Thirdly, it’s important to understand that slavery worked a little differently in Missouri than the rest of the slaveholding South. While plantation slavery did exist, the primary way that slaveowners profited off their slaves was essentially by renting them out to do gig labor along the Missouri River and in St. Louis. This also meant, however, that the difference between an enslaved man’s labor and a freeman’s labor was often as nominal as the words on a piece of paper.

Here is a blatantly pro-slavery biased description of Missourian slavery from the National Park Service:

Slavery in Missouri was different from slavery in the Deep South. The majority of Missouri’s enslaved people worked as field hands on farms along the fertile valleys of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. St. Louis, the largest city in the state, maintained a fairly small African American population throughout the early part of the nineteenth century. Life in the cities was different for African Americans than life on a rural plantation. The opportunities for interaction with whites and free blacks were constant, as were those for greater freedom within their enslaved status. Because slavery was unprofitable in cities such as St. Louis, African Americans were often hired out to others without a transfer of ownership. In fact, many enslaved people hired themselves out and found their own lodgings. This unusual state of affairs taught African Americans to fend for themselves, to market their abilities wisely, and to be thrifty with their money.22

And the Civil War was about state’s rights, hm?

With the constant movement of enslaved peoples up and down the Missouri River, often without the direct supervision of their masters, the state of Missouri had a unique need for a method of surveillance to distinguish between free and enslaved Black bodies, and the Freedom Licenses were their solution to that problem.

German Immigration and Sectarian Violence

Racial animus may have been the core of Missouri’s turn to policing in the 1840s, but the other big driver of state politics during this period was not race and slavery, but rather the omnipresence of sectarian conflict and violence, specifically that between Evangelicals, Catholics, Mormons, and the Southern planter class. As we extensively discussed over the first three parts of this series, the ideals of abolitionism were deeply bound with the American Evangelical movement, millenialism, and the Second Great Awakening; the national politics of the time were a broad conflict between the Evangelical Whig Party and the pro-slavery Democrats, and Missouri was firmly Democratic territory. We’ve been discussing how the Missouri Freedom License program was a prototype for modern immigration enforcement, but it’s important to understand that mass religious migration was also exploding during this time and reshaping the fabric of Missouri’s demographics.

Britain was not the only country heavily affected in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars; the United States also started to experience a significant increase in immigration during this timeframe. Compared to future waves of immigrants, the 1830s were a relatively inactive period of immigration, but compared to previously, it was significant. Notably, the demographics of who was immigrating to the United States also began to shift away from Northern and Western Europeans toward Central and Southern Europeans. While German immigration wouldn’t take off until the latter half of the 1840s, Missouri in particular was an early hub for German immigration to the United States, and St. Louis was one of its early metropolitan centers.

The Germans defied the current political balance in the country in the 1830s. They were not particularly fond of slavery, but they also had a deeply ingrained drinking culture, and were rather hostile to the temperance movement. This flew in the face of the Evangelical ethic. In addition, many in the first waves of Central European immigration were Catholics, which was of course a far bigger problem in the Evangelical mind.

Let us return to Lyman Beecher’s “A Plea for the West” to see what the general consensus among Evangelicals was toward these immigrant groups:

Four years ago the Catholic population was estimated at half a million, and in the single year of 1832 one hundred and fifty thousand were added, and the numbers every year since have greatly increased, and the Catholics predict still greater numbers the current and coming years. […] But the numerical power, without augmentation, would be too small to accomplish the end ; and, therefore, Catholic Europe is throwing swarm on swarm upon our shores. They come, also, not undirected. There is evidently a supervision abroad — and one here — by which they come, and set down together, in city or country, as a Catholic body, and are led or followed quickly by a Catholic priesthood, who maintain over them in the land of strangers and unknown tongues an ascendency as absolute as they are able to exert in Germany itself. Their embodied and insulated condition, as strangers of another tongue, and their unacquaintance with Protestants, and prejudices against them, and their fears and implicit obedience of their priesthood, and aversion to instruction from book, or tract, or Bible, but with their consent, tend powerfully to prevent assimilation and perpetuate the principles of a powerful cast. Hence, while Protestant children, with unceasing assiduity, are gathered into Catholic schools, their own children, with a vigilance that never sleeps, and is upon them both when they go out and come in, and is conversant with all their ways, are kept extensively from Sabbath schools, from our republican common schools, and from worship in Protestant families, and from all such alliance of affection as might supplant the control of the priesthood over them; so, that, as the bishop of Cincinnati said, to a Protestant, ” We multiply by securing all our Catholic children, so that every family in process of time becomes six.”23

This is nativism at its most virulent. Remember that Ohio and Kentucky were the epicenter for the Second Great Awakening – German immigrants would travel West from the coast seeking fertile land to farm, only to encounter hostile Protestant vitriol and get pushed even further west and north. This is why Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Missouri has such significant German populations – the Whiggish Midwest wanted nothing to do with the new German settlers, and so the Germans went wherever they encountered political resistance the least.

You might imagine, given how strongly the Evangelical voted for the Whig party, why the Germans voted for the Democrats. The perception that the German immigrants both disliked temperance (true) and liked slavery (false) surely was only a reconfirmation for men like Lyman Beecher and his ilk of their moral lack. Ohio and Illinois, which were both free states, were hotbeds for such Evangelical thought; comparatively, Missouri in the late 1830s was far less sympathetic to the Evangelical (cum Abolitionist) cause, and thus was a safe haven for German immigrants looking for a fresh start. The Giessen Emigration Society in Germany had described Missouri as “the American Rhineland24;” the St. Louis Genealogical Society writes:

German immigration into St. Louis began in the 1820s, but numbers continued small until the 1830s. Gottfried Duden came to Missouri in 1824 and stayed until 1827 when he returned to Germany and wrote a book on his experiences in Missouri. This book, along with many others of that period, as well as letters from the early German arrivals, promoted German emigration. At the same time in Germany the organization of emigration aid societies, rulers forcing churches to unite, quicker travel by rail as well as steam instead of sail, and rapidly increasing German taxation all contributed to a desire to emigrate. From the mid-1830s until the World Wars, Germans flooded into St. Louis. Because many forms of transportation centered in St. Louis, some only passed through on their way to other Missouri destinations or other states. But because so many stayed, population in St. Louis more than tripled from 4,977 in 1830 to 16,469 by 1840. The first German church in St. Louis was founded in 1834 by German Evangelical Protestants, but it was quickly followed by German Catholics and German Lutherans, who also formed churches in 1835/6 and 1839.25

Of the German hostility to temperance, Heidi Mathis writes:

The newly arrived Germans could not have understood that the Temperance movement had a long history and was bound up with the women’s movement and abolition. They only saw that the natives did not want to allow them their Sunday family time, which happened to include beer. Germans arrived with a culture of Sunday picnics (biergartens), where the whole family enjoyed games, dances, and some beer. These were moderate family times, very unlike the male-only culture of American saloons.26

German immigration was not the only religious force driving the Missourian hostility to the Temperance movement. Mormon immigration to northwestern Missouri was another major driver of state politics at the time, and it would end in significant bloodshed during the Missouri Mormon War of 1838.

The Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, AKA Mormonism, is a religious movement founded by Joseph Smith in 1830 at the height of the Second Great Awakening. Joseph Smith proclaimed himself a prophet who had heard the word of God, and wrote a new Third Testament, the Book of Mormon, which described how the holy people (members of his cult) would go to the holy land of Zion at the end of days to enter the kingdom of Heaven.

The Book of Mormon is a truly perplexing piece of American literature, and I am not going to even attempt to interpret it. It’s an incredibly strange piece of Christian fantasy, appropriation of Native American heritage, and apocalyptic scripture. Here’s what you need to know: Mormons believe to this day that the Garden of Eden was in the current-day boundaries of the United States, and that America is the promised holy land of God. They believed that the holy city of Zion would be founded somewhere on the continent – and in 1838, Joseph Smith declared that the city of Zion would be founded in Jackson County, Missouri.

You need to understand how deeply reviled the Mormons were by most other Americans in the 1830s. Joseph Smith was repeatedly arrested; the Mormon church was forced to move from New York, to Ohio, to Illinois, to Missouri, back to Illinois, before finally getting driven halfway across the continent to Utah, where they remain today. From the perspective of people in Missouri, a foreign and fanatical cult of Evangelicals began to move en-masse across Missouri, claimed a large chunk of land, and declared it the holy site of their hostile religion. This was, to put it mildly, a serious recipe for sectarian violence. Widely considered a heretical cult, the Mormons were also characterized for their policy of total abstinence from alcohol, a disdain which was only compounded in the minds of the “old settlers” of Missouri (i.e. the Southern slaveholders who had moved north to the new slave state less than two decades earlier) by the fact that the Evangelical temperance movement had recently begun its shift toward “Teetotalism,” or an ideology within the temperance movement that called for total abstinence instead of moderation.

The Missouri Mormon War ended very poorly for the Mormons. Missouri Digital Heritage describes the event:

It soon became clear that Missouri non-Mormons and Mormons could not live in the same area harmoniously. In 1836 a “separate but equal” proposal was finally devised to solve this problem, whereby the state legislature created a new county, “Caldwell,” in northwest Missouri as a Mormon refuge. But the booming Mormon population, swelled by the immigration of thousands of eastern converts doomed this to failure, as Mormon settlers burst the borders of Caldwell County and spilled into neighboring counties. Violence broke out again at an election riot in 1838. Old Settler mobs and Mormon paramilitary units roamed the countryside. When the Mormons attacked a duly authorized militia under the belief it was an anti-Mormon mob, Missouri’s governor, Lilburn Boggs, ordered the Saints expelled from the state, or “exterminated,” if necessary. The conflict’s viciousness escalated, however, even without official sanction, when, on October 30, 1838, an organized mob launched a surprise attack on the small Mormon community of Haun’s Mill, massacring eighteen unsuspecting men and boys. Over the next year, around eight thousand church members, often ragged and deprived of their property, left Missouri for Illinois.27

Fun fact: Missouri remains to this day one of the most alcohol-friendly states in the entire nation! It all goes back to this perfect storm of politics, religion, racism, and immigration that coalesced into a very hostile political climate for the Whigs.

So, let’s recap. By 1837, there was a constant movement of Blacks, Mormons, Germans, and all other manner of settlers and travelers along the Missouri river, making St. Louis one of the most important transit hubs in the country. Moreover, Missouri had begun to establish a significant record of deporting “undesirable” citizens; first the Indians, then free Blacks who failed the Freedom License test, and finally the Mormons in blood. But despite all of this hostility to foreign movement, the number of people flowing through and across Missouri each year was only increasing exponentially (and would continue to do so for the next century).

Prior measures to control the public and their movement through Missouri had become a critical priority for the state. Drastic measures were required.

The 1837 Murder of Elijah Lovejoy

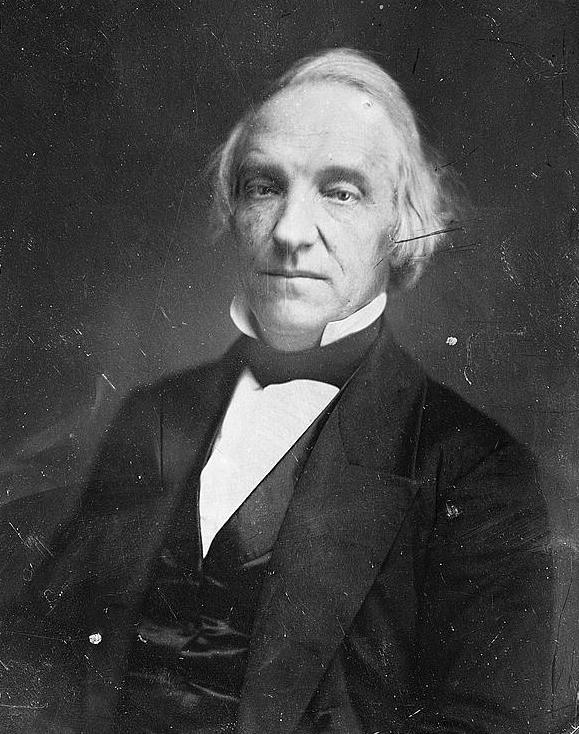

Missouri’s policing against abolitionist politics in St. Louis would slowly escalate over the coming years, and it would become increasingly dangerous to be either an abolitionist or a Free Black in the state. One extremely important piece of abolitionist history in the city of St. Louis was the murder of abolitionist newspaper editor Elijah Lovejoy, who was a friend of Edward Beecher and the AA-SS, and was far better liked on the national abolitionist circuit than he was in the State of Missouri. His positions grew more and more radical over the 1830s until, in 1837, he professed his belief in total abolition. Missourians took this poorly:

Lovejoy’s editorials raised local anger, despite the fact that they increased the paper’s national circulation. A group of local citizens, including future Senator Thomas Hart Benton, declared that freedom of speech did not include the right to speak against slavery. As mob violence grew over the issue of emancipation, Lovejoy, now a husband and father, decided to move his family to the town of Alton, across the Mississippi River, and in the free state of Illinois, where he believed he could write without fear. When his printing press was shipped to Alton, however, local thugs smashed it when it arrived at the docks. In spite of this, local citizens raised money for a new press, and Lovejoy published successfully for another year. His position on slavery continued to be unequivocal, and on July 6, 1837, he published another editorial condemning the practice. His press was destroyed again that night, as well as his later replacement. Sensing the importance of his work and its accompanying danger, friends of Lovejoy organized a militia in order to secretly buy and install yet another press. The violence escalated further in November 1837. A mob formed at the site of the arrival of the Missouri Fulton, the steamboat carrying the press. They greeted the ship and tried to set fire to warehouse where the equipment was being stored, driving out the militia. As Lovejoy ran to defend the site from impending flames, he was shot. […] Hailed by John Quincy Adams as the “first American martyr to the freedom of the press and the freedom of the slave,” the cruel circumstances of Lovejoy’s death inspired abolitionists across the country, and he became a symbol of reform. Many historians have pointed to his death as a primary catalyst in the fight against slavery. History also remembers Lovejoy as a defender of the First Amendment freedom of the press, for which he is remembered as the first of more than 2,200 names on Washington, D.C.’s Newseum’s Journalists Memorial.28

Lovejoy’s murder is important for a couple reasons. Firstly, Elijah Lovejoy lived and published in Illinois, not Missouri. His death across state lines reveals an increasing belief among White Missourians that their local politics could not just revolve around their own state; any effective pro-slavery regime would need to control the state politics of Illinois as well. Secondly, the murder reflects an extension of Southern policing practices that placed the death penalty upon anyone trying to disseminate abolitionist literature. This was not an extra-judicial killing in the minds of Southern democrats; it was master’s duty to kill a slave found with the tools of his liberation. That it was a white man in Illinois made little difference when they saw him as a threat to their livelihoods and way of life.

Thirdly, I want to draw your attention to the central role of the steamboat in this narrative. For slave owners in St. Louis in 1837, here was a direct example of foreign malfeasance creating an armed abolitionist militia to transport inflamatory publishing materials in secret, using the Mississippi River to do it. If Lovejoy could “hijack” the steamboat waterways to bring those abolitionist Evangelical ideals into Missouri, then that meant that anyone could do the same. It stood to reason, then, that so long as the Illinois Evangelicals had leeway to come and go from the state as they pleased, there would always be the possibility of enslaved Blacks simply boarding a steamboat and leaving for safer waters.

Fourthly, as Molly Wicker mentioned, Elijah Lovejoy became a nationwide martyr for the abolitionist cause among Evangelicals in the years following his death. His murder attracted national attention, but perhaps the most significant commentary came from one Illinois State Senator Abraham Lincoln, at that point a rising star in the Whig Party. Wicker observes:

In 1837, officials in Illinois made little comment about Lovejoy’s death, with one notable exception. Twenty-eight year old State Representative Abraham Lincoln stated publicly: “Let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own, and his children’s liberty . . . Let reverence for the laws be breathed by every American mother . . . in short, let it become the political religion of the nation . . .” The unjust murder of Lovejoy seems to have been a seminal event in the formation of Lincoln’s political views. Twenty years after Lovejoy’s death – and before becoming president – Lincoln wrote to his friend, the Reverend James Lemen, reflecting, “Lovejoy’s tragic death for freedom in every sense marked his sad ending as the most important single event that ever happened in the new world.” (March 2, 1857). He went on to say, “The madness and pitiless determination with which the mob steadily pursued Lovejoy to his doom marks it as one of the most unreasoning and unreasonable in all time, except that which doomed the Savior to the cross.”29

I agree with President Lincoln’s assessment: the 1837 murder of Elijah Lovejoy is one of the most important turning points in American history, though with the benefit of hindsight I do believe that it was more symptom than cause. This was perhaps the first time in American history that we begin to see the South’s vision for a Peelian police state in the North unfold; a mandate of censorship on private citizens, patrolled by the mob of the public rather than the federal jurisdiction of the state. When Lincoln is alarmed at the disregard for the law, he is recognizing the earliest symptoms of what would ultimately become the ruling mandate of the Confederacy; small wonder, perhaps, that he would proceed to dedicate his entire life and career to fighting that Confederate ideology, right up to the day that it shot him in the back of the head.

St. Louis, MO: America’s First Crossdressing Ban

I have spent a ridiculous amount of time explaining the history and politics of Missouri in the 1830s to you because it’s crucial you understand that Southern Democrats used the state of Missouri as an incubator, just as national Republicans continue to do to this day. Missouri is a deeply right-wing state, but it also shares many characteristics and political imperatives with its more liberal neighbors in Illinois, Ohio, and Kentucky. The implementation of successful conservative policy in Missouri can therefore be exported across the broader Midwest, even to liberal states who might otherwise balk at a right-wing suggestion. Missouri’s lingering DNA as a “northern” or “border” state combined with its unique geography and colonial history have positioned it perfectly as a testing grounds for an American politik of recuperation. It is a very old strategy, and one that continues to deliver results to this day for American Conservatives.

Elijah Lovejoy’s murder in 1837, much like the Freedom Licenses of 1835, was a Southern Democratic experiment to see how much repressive violence the people of North would tolerate on their own soil. If a mob of white Missourians could murder an white abolitionist in Illinois and get away with it, there was very good reason that Missouri’s new program for policing private citizens could be replicated even in Whig strongholds like Illinois and used to keep abolitionist speech under strict control and out of the public circulation.

Fortunately for the Southern Democrats, the Tory administration in the UK had demonstrated a very clear roadmap for taking “vagrant” violence and turning it into a militarized metropolitan police force, one which lawmakers in Missouri did not hesitate to follow.

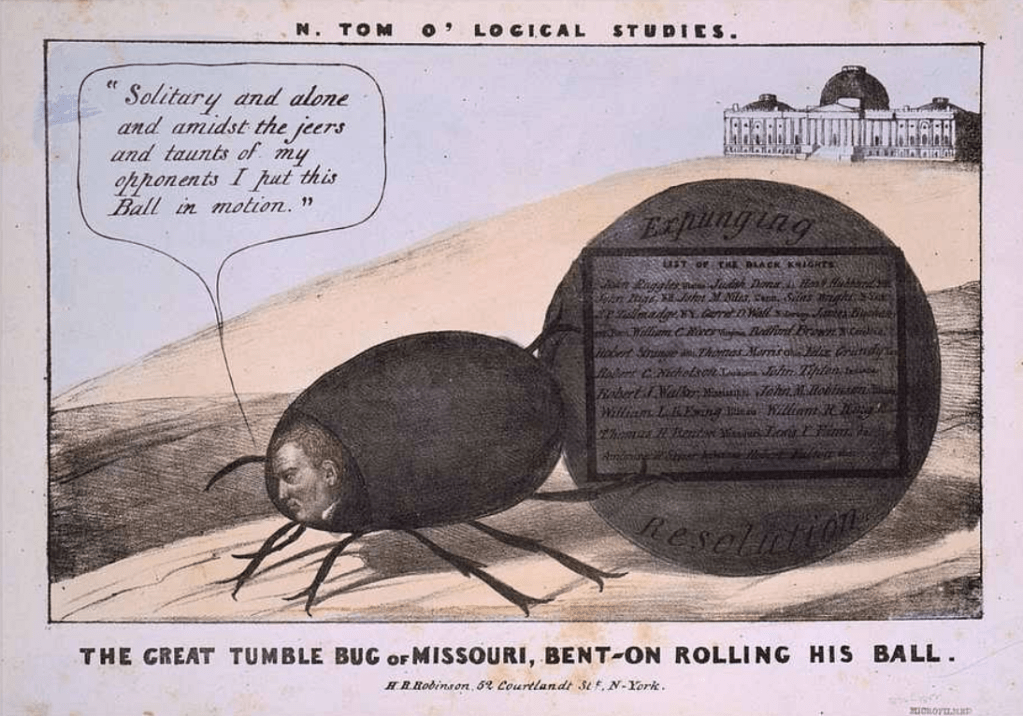

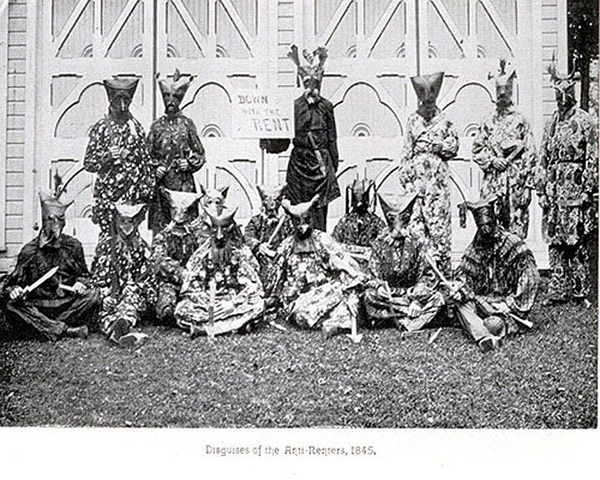

Racialized Cross-Dressing in Early American Minstrelsy