Every so often, I’m asked about whether I’ll take a look at a project from a transfeminine artist outside of the literary sphere. Usually it’s writing adjacent – TTRPGs, visual novel games – but I occasionally get requests to cover music, theater, and art too.

I tend to decline these invitations for a number of reasons. I’m not nearly as knowledgeable or qualified to discuss punk rock or impressionism as contemporary literature; and even on the rare occasions when I am, I have some serious workaholic tendencies that I have to actively work against. My giant stack of unread trans novels is already overwhelming enough without adding more artforms!

That’s not to say that I don’t appreciate a solid piece of trans art in other mediums, though. I watched The People’s Joker earlier this year and enjoyed it; 1000 Gecs is still in my regular music library rotation; I’ve tried my hand at Celeste, though I’ve never been good at platformers and didn’t get very far.

The landscape of trans media criticism is already bare enough, but it’s rarer still to find any sort of comparative or inter-disciplinary analysis. It’s a feedback loop – with fewer critics to share the load in any one genre, it becomes harder for any one critic to leave their niche if they want to achieve any depth or rigor of study.

Early trans arts criticism was often multi-disciplinary, not because it had any interesting aesthetic or comparative analysis about the various mediums, but because the authors literally had no other reference points for trans art. In short, the covered works were trans first, and literature or photography or drama second. To my mind, the emergence of dedicated fields of trans criticism that don’t burden analysis of literature upon art or music, etc., is one of the most important indicators of how trans art has come into its own in the last few years. But this new critical moment also creates a good deal of opportunity to return comparative analysis to the conversation – not out of obligation or misplaced cross-identification, but out of a genuine interest for how these aesthetic frameworks manifest differently across the various mediums and fields.

I don’t turn down review copies of non-literary artforms because I find them unworthy of coverage. Anything but. Rather, I believe that one of the most important critical innovations of the contemporary trans era is our ability to treat with artforms on their own merits and principles; to differentiate, to taxonomize, to pose as aesthetic objects independent of the identity of their creators.

All of this to say – when I was presented with a copy of Erica Rutherford’s artbook at Octopus Books last month, I politely declined to buy it (it was also very expensive). A local friend and I were out on a bookstore crawl; I catalogued Erica’s name in the back of my mind and promptly forgot about the whole interaction.

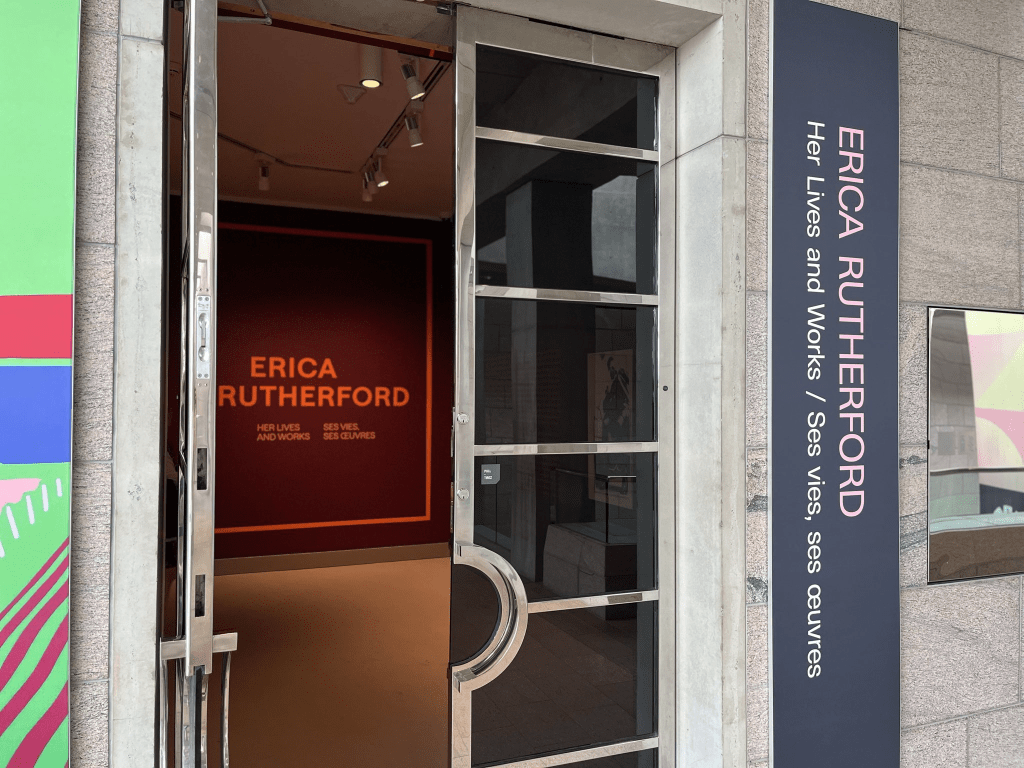

Erica Rutherford (1923-2008) was a transfeminine author, painter, photographer, and filmmaker, whose career spanned decades and took her from the London to Missouri to her eventual home on Prince Edwards Island. While she has been largely obviated from the conversation on 20th Century art, her work is currently experiencing a new resurgence thanks to a special exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada. The exhibition is titled Erica Rutherford: Her Lives and Works, and it will be open until October 13th, 2025.

Though I had been told about it, I had absolutely no recollection that this special exhibit was currently open when I decided to take my grandparents to the National Gallery today. It didn’t click until we had already finished the main exhibit – I was sitting in the atrium, starting up at the Erica Rutherford poster, thinking, ‘Wait a second, I’ve heard that name…’ Lo and behold! Trans art by total coincidence, sitting right in front of me, waiting to be experienced.

It’s hard to stress how unusual and novel this felt. Finding any trans art can be like searching for a needle in a haystack, and for it to happen randomly, at a national gallery no less, was somewhat astonishing to me. I was in DC less than two months ago, where the Smithsonian has been making recent headlines for their early attempts to remove ‘woke’ content from their collections. Coming from that paradigm, this was a total system shock.

While the primary curator of the exhibit, Pan Wendt, is not himself trans, he described in an interview earlier this year how trans voices were central to the creation of this exhibit:

With most exhibition projects I have to contend with my own blind spots and areas of ignorance, but this one in particular I had plenty to learn if I was going to do justice to Erica and her work. For that reason, it really had to be a bit of a collective undertaking. Decisions were often heavily influenced by Erica’s own words, stated in her writings, or by conversations with trans scholar Eva Hayward, who has written extensively on Erica, or with the help of the incredible research of curatorial assistants (especially Lee Richard, who is himself trans); there’s also the Rutherford family. Among my colleagues, Trevor Corkum in particular was generous with advice in areas I wasn’t too sure about, especially with respect to didactic texts. There were other ethical questions associated with this show, and some I’m still grappling with, as we begin to think about publication. For example, how to present the 1949 film Erica produced in South Africa, which had a mostly Black cast and was intended for a Black audience. I relied on the opinions of a Black South African film scholar when I was thinking about how to contextualize this work in the exhibition. He described the film (which looks very problematic now) as both “patronizing” and yet extremely important in the history of Black South African self-expression and the process of eventual political liberation. For this reason, I felt it was important to show, but also to put in context.

This is fantastic on a lot of levels, and I can attest that the “trans lens” was very much present. While gender and trans issues are a theme of the gallery, nothing in the presentation or marketing hawks it as a ‘TRANSGENDER EXHIBIT,’ nor does Rutherford’s trans identity ever feel like more than a supplement to the art itself. Moreover, the lack of romanticization or rosy critique is perhaps even rarer than the understatement and nuance of the trans themes themselves. Wendt’s Erica Rutherford exhibit never shies away from Rutherford’s flaws and shortcomings; it does not sugarcoat or wave off her aesthetic choices. At every room and turn, Rutherford is treated with the same consideration and gravitas as any of the cis artists in the gallery, and that’s an enormous compliment to the curator and his team when it comes to the presentation of trans art.

When I took Sociology of Art in college, one of my primary frustrations with the class was how many of the fundamental assumptions were grounded in art galleries and the museum space. While I took away many of the key frameworks I use today – market, production, and tool focus, historical materialism, field analysis, etc. – I was continually struck by how poorly the physical geography of the gallery space mapped onto the physicality of books. Gallery art was to be seen, not touched or used. Its possession and valuation as a commodity and wealth object seemed distant from mass reproduction of literature, or so I thought.

The more I come to understand the politics of literary value, however, the more I understand that literature isn’t so different from art in a sociological lens; it merely operates on a far smaller economic scale. Inclusion in an austere national gallery space or a sale for millions at a Sothesby auction can be articulated within a similar framework as the politics of inclusion at a chain bookstore or a federal library, dis15 – Should Critics Read Bad Books?parate as they might seem; and there is enormous value in the comparison. An austere and internationally-prestigious special exhibition like this one offers us an unique foil to interrogate the social economies of trans literature, and once I realized what I had stumbled upon, I leaped for the opportunity.

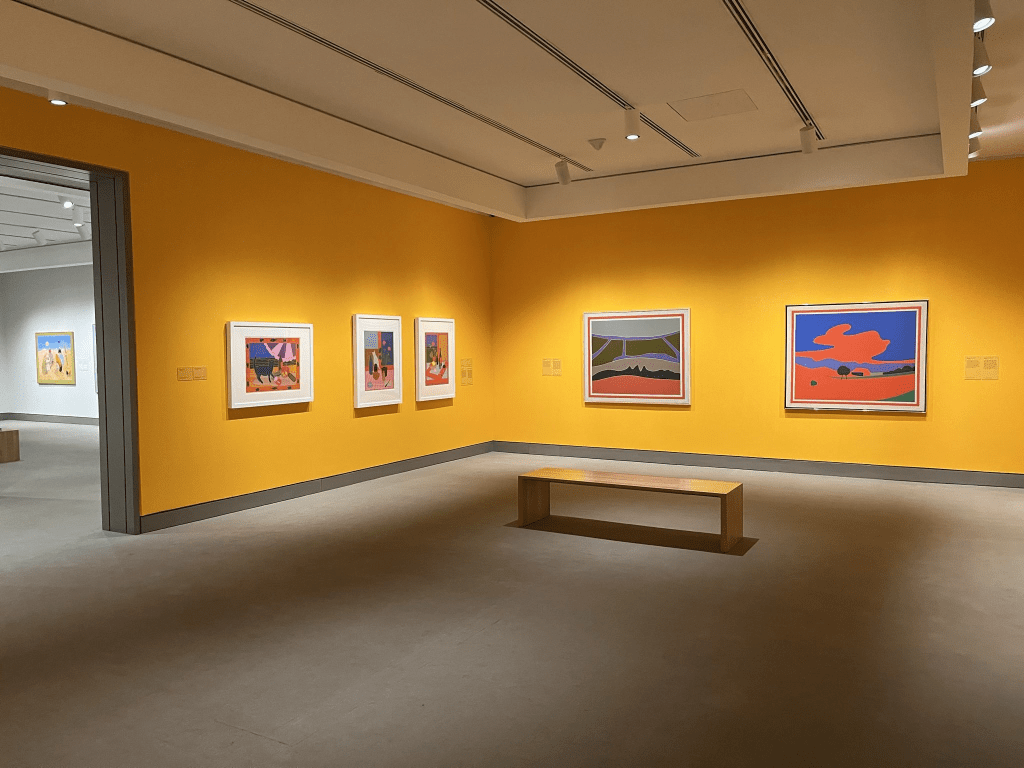

One of the most striking elements of this exhibition was the sheer amount of space devoted to it:

Perhaps more than any of the artwork or curatory text, it was the negative space within the exhibit that struck me as the most radical statement. Rutherford’s work was not confined to a single room, nor did she share the floor with other artists. There were, by my best count, no fewer than seven full rooms in the exhibition entirely dedicated to her work. I honestly can’t think of a single trans artist in any medium that I’ve ever seen such a broad and concentrated spotlight on.

I may sound shocked here, but I think it’s important to note that the museum very much needed every inch of space it used. Rutherford’s work spanned a dozen different styles, multiple mediums, several decades; it covered her filmography and photography; the number of rooms was in this sense unremarkable. The size of the exhibit is rather of remark because it highlights how often trans art is forced into a cramped space; how complexity and nuance are bulldozed by bigotry and social constraint. In a world where this exhibit took up a single room, it would be an absolute bombardment of incoherent styles. Entire chunks of the story would be missing from the picture.

This exhibit spoke to me today because it gave me that same sense of purpose that I take into my own critical work, the desire and determination to focus in on a specific subset of trans art to give it the room to breathe. Transfeminine fiction is obviously a broader category than the work of a single artist, but part of what TFR has aimed to circumvent is the ‘cramped room’ phenomenon, where novels of note are cherry-picked and stuffed together out of an artificial demand for scarcity.

At its best, the fine arts can make a powerful statement about cultural values and national priorities. That an exhibit like this found its home in the National Gallery of Canada, essentially claiming Erica Rutherford as a Prestigious Canadian Artist, is a significance that ought not to be overlooked.

(This form of nationalistic claiming reminds me quite a lot of how Quebec champions the work of Gabrielle Bouliane-Tremblay, but I digress).

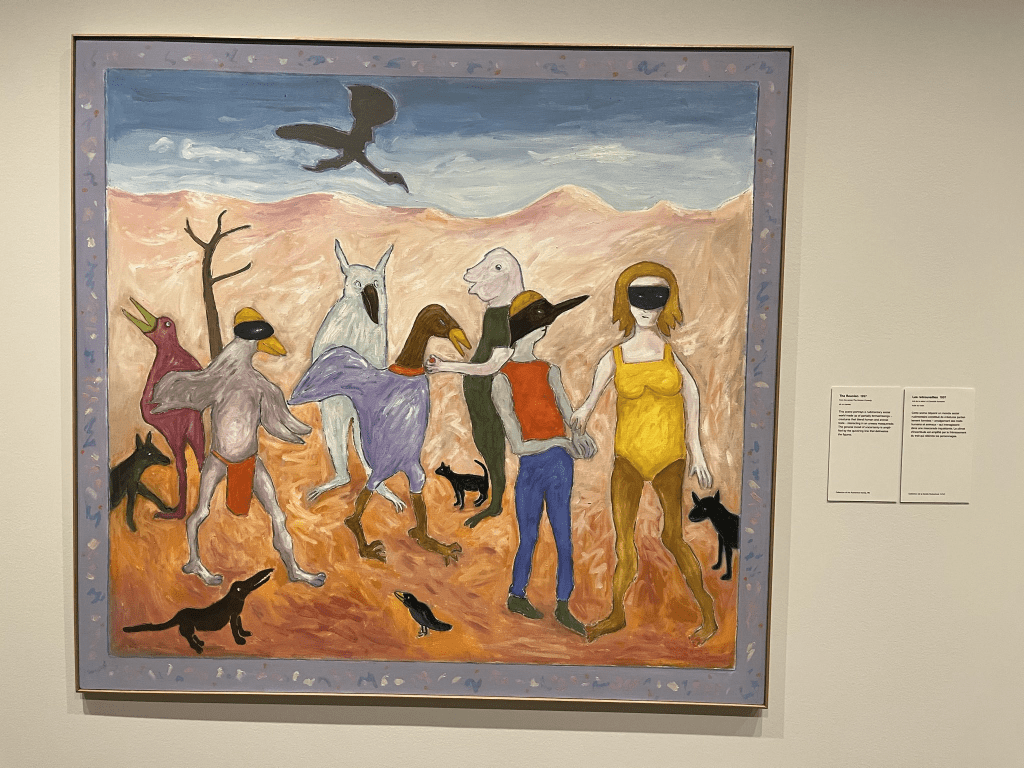

Regardless of whether we read the museum space as a nation-building project, it’s fascinating to see the way that some very explicitly transfeminine art gets interpreted and framed within such an austere and federal setting. Especially toward the middle of her career, Rutherford’s work contains explicit depictions of transfeminine bodies and hermaphroditic (her words) sexual characteristics. I was caught by how the exhibit framed the most sexually-charged paintings around the lone photography section, which contained one thing I genuinely never thought I would see in a museum: an honest-to-god transition timeline.

For a moment, I was genuinely wondering if someone had turned a Reddit post into an art exhibit.

There’s an important conversation to be had here about narrativization and the role of the museum. In any exhibition, but especially in one like this organized as a chronological retelling of an artist’s life, the curatorial choices of the museum can have an outsized effect not only upon how its visitors will perceive the art, but on the artist’s legacy too. This is especially true for a relatively obscure artist like Rutherford. Walking away from the exhibit, I’m left with the open question – did Rutherford’s paintings grow more explicitly (trans)sexual as she entered and proceeded through her transition? Or did the exhibit merely organize its pieces in such a way as to frame real photos of a gender transition around abstract imagery of hermaphroditism?

I don’t know the answer, but it’s the sort of thing that entering the physical gallery space forces you to consider in a way that simply viewing an online photo of an artwork never will.

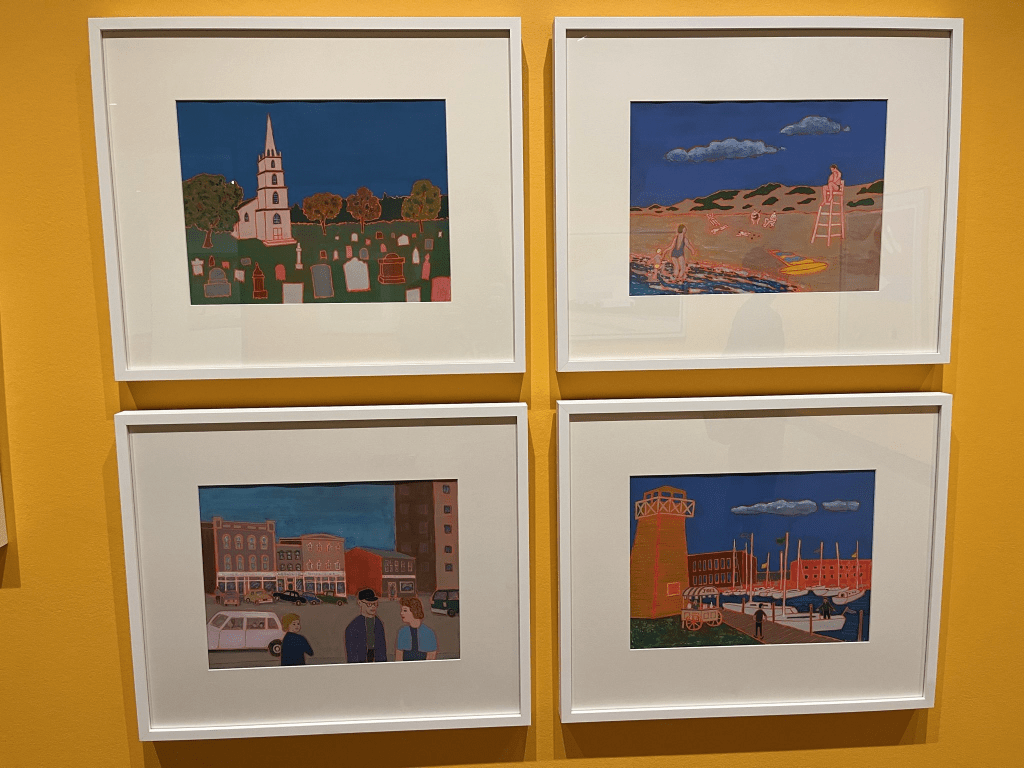

Equally fascinating to me is the way that Rutherford’s work is depicted as a sort of national triptych. Her pre-transition (male) art is situated in London; her transition-era (transsexual) art is situated in America; and then her post-transition (female) art is situated in Canada, where she lived for the rest of her life and eventually passed away. There is a shift once we enter the ‘Canada’ stage of the exhibit where Rutherford’s work loses much of its hermaphroditic edge. The paintings of her American era depict genetalia and grotesque forms; but in Canada, we see the sexed bodies abstracted into distorted animals; we learn that Rutherford illustrated children’s books, and we see pastoral landscapes that she painted in her later years.

I take particular note of the landscapes and other quaint depictions of Canada because it seemed to echo a strong throughline from the permanent exhibition of Canadian art that I had walked through just minutes earlier. The National Gallery of Canada is filled, and I do mean filled, with rosy landscapes of Canadian nature, and waterfalls, and snowy log cabins, and trappers in the woods, and cresting mountains, and moonlit city squares, and all other manners of beautiful panoramas of an idyllic Canadian life. When I speak of the museum-space as a nation-building project, this is exactly what I’m referring to.

The Erica Rutherford exhibition does a remarkable job at showcasing a transfeminine artist to a degree that I’ve basically never seen before in a national art institution. But its primary aim seems to be establishing Rutherford’s Canadian identity and her place within the Canadian national aesthetic project. In this sense, transfemininity is merely adjunct to the broader aims of the exhibit; it serves as a subtle narrative device to build a vision of Rutherford as a Canadian Artist who upholds Canadian Values, and even in its remarkable breadth, still has not escaped those quiet undercurrents of instrumentalization by the state.

Despite all this, I still found Rutherford’s Canada-era work to have that distinct flair of the fin-du-siècle transfeminine scribble style. Her later painting especially reminded me of Sybil Lamb’s drawings, or of the illustrations on Rachel Pollack’s signature Shining Tribe Tarot deck.

Ultimately, no matter what conclusions we draw about the exhibit itself, it’s tremendously cool to see a transfeminine artist given such a significant platform at a venerable institution, and cooler still that I went into it completely blind. It really made my day, so I wanted to do this quick little write-up to share it with y’all, and hopefully leave you with the same thoughts and questions on my mind tonight.

If you’re in Ottawa at any point before October 13th, I would highly recommend stopping by the National Gallery and giving this special exhibit a look. It’s absolutely worth the trip.

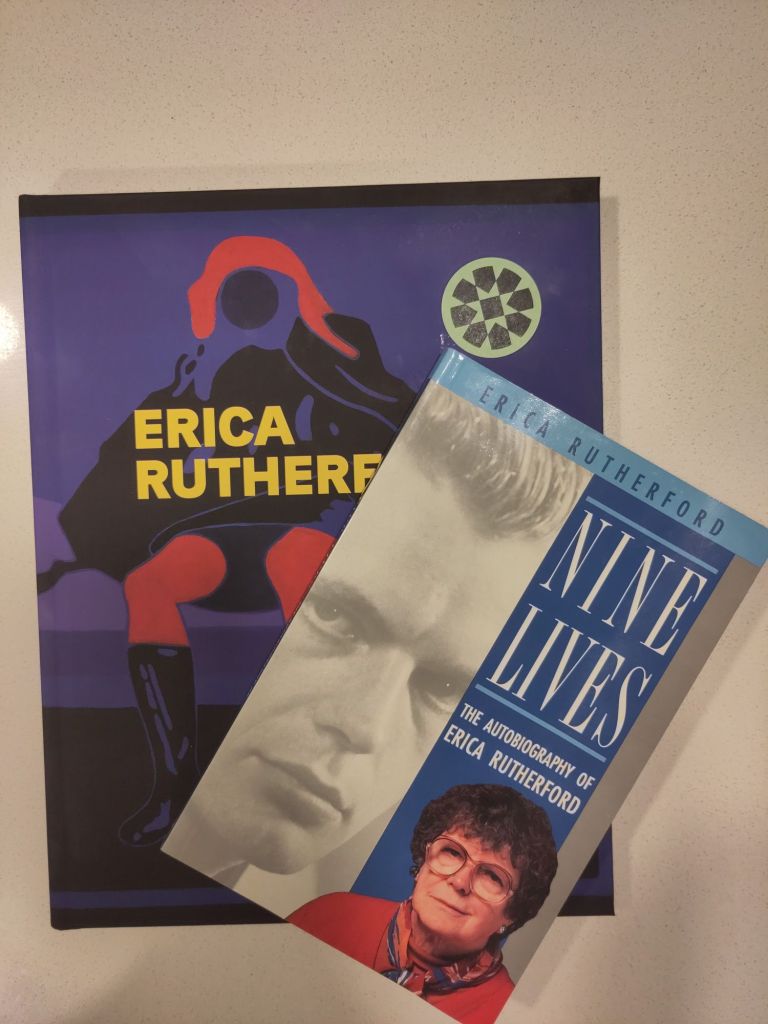

Oh, and I picked up some goodies in the gift shop on my way out:

What can I say? The art was just that good!

Happy reading, Beth 💕

LAST WEDNESDAY: #13 – Showcasing the Transfeminine Nominees for the 2025 Lambda Awards

NEXT WEDNESDAY: #15 – Should Critics Read Bad Books?

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.