This essay is a follow-up and response to the first essay we ever published on this website. If you want to read the first essay in this series, “The Problem with Contemporary Transfeminine Literary Criticism,” you can find it here.

The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature

I have a confession to make, my dear reader. When I posted my first essay last week (link above if you missed it!), I thought that I had found everything there was to find in the realm of transfeminine literary criticism – and let me tell you, I have been absolutely delighted to be proven wrong. You guys have absolutely shown up with the book recommendations, websites, projects, articles; the sheer amount of creativity and enthusiasm has been humbling, and it’s been such an honor to engage with everyone over the last week. But one book that I missed was a much larger oversight than anything else, and it’s important enough that I wanted to dedicate an article to covering it.

The volume in question is the Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, a 523-page chonker of an academic reader that currently costs $280 on Amazon ($58.99 for the e-book) and features forty-three contributors writing across a wide range of literary interests: from contemporary literature to pre-trans genderqueer writers from the centuries prior, spanning mediums as diverse as fiction, performance poetry, manga, comics, fanfiction, and more. The scope of this book is very ambitious, and on that merit it should be lauded.

KJO15, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons1

On the question of its origin, this handbook has a confusing story. The key figure to know here is one of the two lead editors, Douglas A. Vakoch, an American psychotherapist and astrobiologist (yes, you read that correctly), who has dedicated his career to attempting to communicate with extra-terrestrial life. He appears to have come to trans research through his connection to Susan Stryker, who works with him on the board of his organization METI International (Messaging to Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence), which appears to be the connection which led to the production of this volume. Dr. Vakoch has a longstanding interest in the field of ecofeminist ethics, with his first publication on the topic spanning back to 2011 with “Ecofeminist ethics and digital technology: A case study in Microsoft Word”2 and sporadically continuing throughout the 2010s.

Dr. Vakoch’s first publication on trans-related issues came through his 2020 edited volume Transecology: Transgender Perspectives on Environment and Nature, also from Routledge. In Susan Stryker’s introduction, she offers the following thoughts:

I have been asked to write this foreword, I suppose, because more than quarter-century ago, in an essay that expressed my affinity and kinship with Frankenstein’s creature on the basis of my “unnatural” transsexual embodiment, I critiqued notions of Nature that were but bedeviling lies, fictions that cloaked, beneath the pretense of inevitability, the machinations of social power so detrimental to my life and to the lives of those like me. The enemy of my nature is a Nature that is home to Man, but not to me. I asserted then my sense of life as being filled with monstrous potential in which I acknowledged my “egalitarian relationship with nonhuman material being” (Stryker 1994, 240). It hurts, and is dangerous, to be dehierarchized, to lose human status by falling outside of norms and thereby being subjected to violence, but decentering the tangled webs of trans-huManinimality nevertheless offers a better ethical starting place for enacting our relationship to Being than trying to prop up a spurious anthropocentric privilege. This is where transecology begins for me.3

In my first essay, I largely avoided a discussion of Stryker’s work. While it constitutes an important piece of transfeminine literary canon, a critique didn’t suit the piece. In this context, however, it does become relevant to the conceptuality and production of this volume, so we’ll be discussing Stryker later in the essay.

Dr. Vakoch’s liaison with Stryker and his coordination with scholars of Trans Studies from around the globe provided the grounds for a deepening interest in trans voices and literatures. In 2022, Dr. Vakoch edited a second volume entitled Transgender India: Understanding Third Gender Identities and Experiences4, before connecting at some point in the interstitial period with Dr. Sabine Sharp, who had recently completed a PhD in English and American Studies from the University of Manchester, where they are still employed. Using Dr. Sharp’s expertise in the field and Dr. Vakoch’s network (ostensibly developed through Stryker’s decades of organizing work), the pair edited the Handbook of Trans Literature, which was published on April 30th to a silent reception from the broader literary community in academia. As far as I can tell, this essay is the first and only review of any kind of this volume. I have been mindful of that fact during the writing of this article, but keep in mind that you should never listen to a single opinion on a volume of this magnitude. Read critically and mindfully, y’all!

Before I get into my analysis of the scholarship and my assessment of the various ways the Handbook does (and mostly doesn’t) respond to the critiques from my last essay, I wanted to take a moment to appreciate the hard work and dedication that all of these scholars put into this. It’s a disgrace that the academy has paid no attention to it, and Dr. Sharp’s work and Dr. Vakoch’s allyship should be lauded. As I observed in my last essay, many of them are at the beginning of their careers and still finding their theoretical sea legs, working off of a discipline with no attention, infrastructure, or support. Many of the contributors are still students themselves. So, The Transfeminine Review would like to be the first publication to extend an enormous thank you and acknowledgment to Aqdas Aftab, Nicole Anae, Nisarga Bhattacharjee, Katarzyna Burzynska, Kristen Carella, Tesla Cariani, Ananya Chatterjee, Jeremy Chow, Casey A. Cothran, Michelle Deininger, Alexander Eastwood, Tara Etherington, Lenka Filipova, Margaret Galvan, Laura Gazzoli, Aaron Hammes, france rose hartline, Sam Holmqvist, Peter I-min Huang, Sunaina Jain, Alexa Alice Joubin, Sawyer K. Kemp, Chung-Hao Ku, Dean Leetal, Esteban F. López-Medina, Melanie A. Marotta, Nowell Marshall, Michael Mayne, M.A. Miller, Timothy S. Miller, Michael Mlekoday, Todd G. Nordgren, Mariano Quinterno, Emily E. Roach, Eamon Schlotterback, Ayse Sensoy, Sabine Sharp, Tristan Sheridan, Frederick C. Staidum Jr., Kelly Swartz, Jay Szpilka, Erik Wade, Travis L. Wagner, Rowan Wilson, Libe García Zarranz, and Jolene Zigarovich for contributing to this ground-breaking work. Your efforts have not gone unobserved.

That being said, the Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature is a deeply flawed text, one which not only reinforces many of the organizing mythologies that have constrained trans literature in the past, but also one which develops and furthers a variety of new ones. Dissecting and discussing these various cross-article trends shall be the primary subject of this essay.

What the Handbook Gets Right

The goal of this essay is not to diminish the work done by these scholars, but rather to provide a constructive engagement that can furnish the grounds for developing these ideas in the future. To that end, it will serve us to take a brief tour through the Handbook, and discuss several of the things which it does do right.

The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature is split into three sections. The first section, “Core Topics,” takes up the majority of the volume. It provides a overview of a variety of themes, tropes, and schemas of analysis through which trans literature might be read. The second section, “Forms and Genres,” reads various literary genres as trans literature. Finally, the last section “Periods” provides a chronological overview of historical “trans” literatures, looking at genderqueer themes through the latter half of the 20th century.

I want to begin by outlining which parts of the volume I’ll actually be talking about. Aside from the article on Modern Trans Literature, which I found put way too much emphasis on books like Ulysses and The Waste Land instead of networks of genderqueer writers who were producing work at the time, I thought that the final section of the book was excellent and a great primer for anyone who wants a general shape of what current scholarship on trans literature from the 1500s to the 1930s looks like. This project is primarily concerned with contemporary trans literature, so I’ll be leaving that mostly alone. Additionally, I will be focusing the scope of my inquiry where I have the most expertise, the trans novel. This means that I won’t be offering comment on the chapters on comics, manga, performance poetry, or various other mediums that fall beyond my knowledge. Furthermore, there was one chapter on Hijra autobiography and one chapter on trans themes in Chinese literature, which I also don’t have the knowledge to adequately address. All together, that means that in this essay, I’ll only be treating with about thirty-seven articles out of the near-fifty, and that my attention will be mostly concentrated on the essays about the novel and its various trans forms.

There were a few essays that stood out for their exceptional scholarship, and I want to take a moment to appreciate them.

Firstly, I thought that Sharp produced an excellent introduction to the volume, one which hit on my prior concerns. They write:

While this Handbook covers a broad range of creative and critical writing, this only scratches the surface of works available to be read. Turning to my own bookshelves— and focusing on trans-authored fiction of the last 50 years alone—there are dozens of works neither covered in this Handbook, nor discussed in existing trans scholarship. This Handbook offers more than an overview of the landscape of recent literary works published by trans authors—although it does indeed present numerous suggestions for personal reading lists and academic syllabi, as well as starting points for further research. More importantly, however, the chapters assembled in this Handbook work together to disrupt our very understanding of what is meant by “trans literature.” Many of the chapters included here push back against the elitism and conservatism at work in some conceptions of “the literary.” Such chapters analyze works often sidelined or trivialized within the study of literature, such as children’s fiction, fan fiction, slam poetry, self-published novels, mass-market autobiographies, crime fiction, thrillers, comics, and manga. Reading these texts as works of trans literature asserts their significance to trans study, while challenging the idea of “the canon” from which trans writers have so often been excluded.5

This is fantastic. Dr. Sharp acknowledges that the scarcity of trans texts is often an artificial production by a cisnormative industry, and poses a broader world of trans literature that exists beyond the purview of this text. This is a very necessary acknowledgment, but also one that foreshadows many of this book’s biggest problems. Indeed, it is often evident throughout this text that its scholars are aware of a far larger corpus of trans literature than they present to their readers. I wish that we had seen more of that corpus on the page, but acknowledging it is an important step, and I respect that this volume was not trying to be comprehensive and admits so upfront.

The first article in this volume comes from Nicole Anae, who had previously collaborated with Dr. Vakoch in Transecology. “Culture and Trans Literature” is largely a definitional essay, but it makes some of the most important observations in the volume, neatly encapsulating The Transfeminine Review’s mission:

By viewing trans culture as a “tradition,” it is possible to explore the intersections of culture and trans literature as both convention and institution. My purpose here is to incorporate the subjective and objective aspects of trans culture as a human group with distinctive traditions and practices, the subjective side of which underlies the essential core of various trans cultures as expressed with and through literary creation. Trans literatures thus reflect a cultural tradition constituting the distinctive achievements of trans people “including their embodiments in artefacts” (Kroeber and Kluckhohn 1963, 357).6

In my notes, I wrote “YESYESYES” next to this. This is exactly right! So many accounts of trans literature completely ignore the submerged histories of trans literary communities that produced it. I think that Anae hits the nail on the head by centering the human in trans literature. Many of the articles in this volume concern various themes of the trans as a monstrous thing – trans aberration, transhumanism, trans ecology, trans cyberpunk, trans AI, hell, even trans plants and trans water (two themes which inexplicably have their own article in the first section, despite notable absences like the lack of articles about transphobia, sex work, or publishing discrimination). Most of the best articles in this volume, by contrast, firmly and resolutely center the human, posing their transness not as a curiosity to be studied, but as a materially vested interest that arises from the forces which draw the trans person toward fiction in the first place. Anae’s picture of trans literature is a glowing example of the humanity and care that this field has the capacity to embody.

It should be noted that my personal project is dedicated to specifically transfeminine authors, whereas this volume seems more interested in trans topics and themes without paying much attention to the specificity of the various communities within it. There’s a proper mix of transmasc, transfemme, and non-binary scholars, and I’ll be treating with them all in this essay. One excellent essay comes from Travis L. Wagner’s “Archival Speculation and Trans Literature,” which poses an important question about how we extend “trans” literature as a concept into the past. As most of you likely know, “transgender” is a recent term – even when juxtaposed against the literature of the “transsexual,” uneasy tensions begin to gather, never mind older and more forgotten language. Wagner writes:

Trans embodiment possesses an inherently fictive relationship with the past. Although acknowledgment of transgender identity is centuries old, the burden of proof of labeling moments of trans history within the archival record remains contentious. Scholars and historians alike contend with the burdens of ahistoricism, understanding that a lack of context means no figure can be explicitly transgender without declaring themselves as such. Equally, to assert one figure as definitively transgender produces a dangerous precedent for boundary setting that essentializes transgender embodiment within the archival record (Beemyn 2013).7 […]

Until broader concerns around archival truth and its inherent biases can be confronted, trans historiography will remain an act wholly invested in the fictive. Truth, after all, is something trans people have lived throughout history, even if that truth remained hidden from others.8

This passage gets at an important truth that most people in trans literary circles don’t fully grasp. There is a persistent desire to retroactively assign ‘transness’ to figures throughout history – Chevalier D’Eon, Elagabalus, various figures in myth, so on and so forth. This trend is best encapsulated in an article which Rachel Pollack wrote in 1994 entitled “Archetypal Transsexuality,” which talks about the polymorphism of gender in myth, comparing figures as diverse as Inanna, Aphrodite, and the Virgin Mary as a transsexual figure of goddess worship (think Wrath Goddess Sing or Yemaya’s Daughters). One might also remember that Leslie Feinberg draws heavily on mythological imagery of transness in hir famous article “Transgender Liberation,” relying on those histories to stake a claim to the ontological historicity of trans identity. This trend of mythologizing “trans” figures in history is, to my mind, reminiscent of a Campbellian approach toward history, one which seeks an organizing mythology that can generate homology across disparate culture and time. This ‘trans monomyth,’ so to speak, is a common trope. The essential work that Wagner does in this essay is to differentiate an ‘archetypal history’ that embraces such figures as trans from an ‘archival history’ that deals with the actual textural reality of ‘gender’ across time, and problematizes the notion that engaging with the former is a productive motion toward the latter. This is something that scholars of both trans literature and history would do well to observe.

By my token, the best essay in this entire volume is “Teaching English as a Foreign Language and Trans Literature” by Esteban F. López-Medina and Mariano H. Quinterno. López-Medina and Quinterno deliver us a fascinating experiment in which fiction from Jenny Finney Boylan and Camila Sosa Villada were used to teach ESL, accompanied by an array of data about the impacts on students and observations about potential implications for a trans-informed pedagogy moving forward. Not only is this article done extremely well, but it also strikes at a much broader issue beyond just the ESL classroom – the importance and impact of teaching trans literature in schools, and why it matters that conservatives and fascists around the globe keep banning our books. Their research offers a real material look into how exposure to trans themes in literature can shape outlooks on trans rights, and it should be essential reading for anyone who’s invested in fighting against the wave of book-bannings that have been plaguing the United States.9

I found that by the second section of this reader, most of the articles were merely replicating analysis from the first section with a narrower scope. In this sense, I have less to say about the theoretical underpinnings of these explorations – it becomes much more a question of how well each respective genre is handled. Almost every article in this volume touches on the trans autobiography in one form or another, but by far the most successful is the article dedicated to it, “Life Writing as Trans Literature” by Eamon Schlotterback10. If you’re looking for a piece about the trans autobiography to cite, this is the one. The best article in the genre section is Sabine Sharp’s “Science Fiction and Trans Literature,”11 which gives a very exciting window into what the upcoming Routledge Handbook of Science Fiction and Fantasy might look like. Michelle Deininger’s “Young Adult Literature as Trans Literature”12 was also quite good. Finally, I thought that “Minor Literature as Trans Literature”13 by Aaron Hammes provides us with a much clearer Deleuzean picture, one far more adequate as capturing the minor elements of trans literature as a genre. If you’re looking for a “trans literature is minor literature” argument, I would recommend this article over Salah.

“X as Trans Literature”

And now we come to the issues. You may have noticed by this point that every essay in this book takes on the rhetorical form of “X as/and Trans Literature,” wherein a concept is presented before the metric of “trans literature” and evaluated at such. There are a number of issues with this approach, and we will go through them one by one.

Firstly, by posing every single concept against a homogenous “trans literature,” there is not a single article in this entire book where “trans literature” is posited as beginning from any unique traits which cannot be found and describe in pre-existing literary terms. There is a certain framework of subordination, then, where no matter how stark or unique an author’s observations about transness are, it must be taken in the context of a cis idea. There is, for example, no article about the “sad girl trans novel” in this volume – there are articles that use the idea, but because they cannot premise them upon it, an entire genre of contemporary trans literature is diluted across dozens of articles, its cohesiveness disrupted altogether.

What effect does this have upon the text? Firstly, it produces an enormous amount of bloat, which perhaps this volume’s biggest problem. When every single scholar must start from a cis idea and arrive at a trans idea, it creates unnecessary explaining and groundwork to justify the mere idea of a ‘trans’ version of that trope/genre/theme. Perhaps in an individual article, this would be excusable. However, it sinks this collection of essays because of the sheer repetitiveness of the endeavor.

The issue is not that the article recites the history of the cis gender novel, the history of the transition narrative, the history of trans studies. No. The issue is that nearly every article in this volume – often even if it has little to nothing to do with its topic – recites the same history about these three things.

Repetition of the same lines about Conundrum. Repetition of the same lines about Sandy Stone. Repetition of the same lines about Nevada. Repetition of the same lines about transphobia. Repetition of the same lines, the same ideas, the same histories, the same mythologies, as though nearly every author in this entire volume got handed the same hundreds books and was told, “Okay, go do theory with this now.”

This is a structural problem with the conceptuality of the Handbook. It could have been prevented by making the first chapter of the book an article titled “A Cisnormative History of Trans Literature,” and then having every article in the book cite that. Instead, even when authors are heavily critical of the colonial and imperial project of the cishet gender novel or the trans memoir, their rote parroting of details taken as gospel reinforces those narratological histories rather than breaking them apart.

Secondly, because no original concepts about “trans literature” can ever be premised, the act of defining trans literature – and indeed transness itself – becomes a near impossibility. Unlike “Girls Like Us” and “Transgender and Transgenre Writing,” two articles that I cited in the first essay of this series which both attempted to provide innovative and detailed explanations for the particularity of trans literature, the Routledge Handbook exists in a state of suspended animation, caught in transit, so to speak, between a defined cis normativity and an ambiguous transliterary object. It is neither cis nor trans, but rather trapped in between, committing to neither and ultimately serving none. The Handbook falls into a pattern of description wherein a topic is proposed and elaborated on first, read into the literary text by a trans person second. Trans books in this volume cannot be described as proposing or dictating the topic of literary analysis – they merely exemplify a literary ideal, and in doing so, allows the author of the essay to say: “This, too, is trans literature.” Books written by trans people are always transgressive or boundary-breaking, never original. They cannot be understood outside of the context of the cis books which preceded them.

In this constant need to overdetermine the trans novel, the novels themselves lose much of their particularity and vigor. What do I mean by this? Let’s take Nevada by Imogen Binnie as an example. Here is a complete list of everything that the Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature claimed Nevada was, in no particular order.

In fact, let’s substitute “Trans Literature” for “Nevada,” just to make it really evident:

- HOME AND NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormative spatiality that shatters norms.

- BDSM AND NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormative demonization or mystification of BDSM that shatters norms. (This article was really interesting for the record, probably the best of the seven).

- DISABILITY AND NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormative ableist ideas about trans healthcare and trans bodies that shatters norms.

- TRANS POETICS AND NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormative ideas about autogynephilia that shatters norms.

- NATURE WRITING AS NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormative ideas about the natural scenery of the West and road travel that shatters norms.

- THE RADICAL NOVEL AS NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormativity that shatters norms.

- MINOR LITERATURE AS NEVADA: Nevada is a groundbreaking novel with a disregard for cisnormative territorialization that shatters norms.

Sure, all of these articles have real things to say about Nevada. I do buy that Nevada is about all of these things! It’s practically a swiss-army knife of a novel! But let’s not pretend like any of these articles are saying anything groundbreaking or unique. It’s the same argument copy-pasted into seven different places with the content switched out for whatever topic the author happens to be discussing in the moment. I’m not saying it’s not interesting. I’m not saying that it’s not potentially useful if, say, you’re writing a paper about how Nevada is the great American road trip novel for our generation. Whatever. What I’m saying is that there is very little argumentation in this entire collection that cannot be boiled down to “X TRANS BOOK IS A TRANS VERSION OF Y CIS IDEA.”

That’s a missed opportunity. But it also hews right back to one of the key arguments I made in my first essay in this series, which I believe now needs elaboration in the context of the handbook.

“Trans as Method”

We turn back here to our quote from last time, where Andrea Long Chu and Emmett Harsin Drager are in conversation over the future of Trans Studies:

[W]hat’s happening [in The Empire Strikes Back] is that Stone is, like most scholars of gender in the nineties (and the aughts, and our own decade), molding her object to fit her theory, which is not by coincidence the same as the then fashionable theory. In other words, the basic narratological form of the medical discourse—what Stone calls a “plausible history”—has in fact remained largely intact. All Stone’s done is switch out the original content of that history (disease, diagnosis, cure) for a different content, namely, the prevailing elements of gender theory in the nineties (performativity, disruption, transgression). In fact, she’s laying the groundwork for the long-standing intellectual move in which the trans person, just through the act of existing, becomes a kind of living incubator for other people’s theories of gender.14

Chu would have an absolute field day with this essay collection. It’s not even ambiguous – the book literally asks us to consider trans literature “as” over forty other things. At no point does it ask, “What is trans literature, anyway?” No, it’s always about the big tent – it’s always, “Why can’t we make this trans too?”

In this picture, “trans literature” is a vacuous entity that contains anything that takes on “trans” characteristics. What does that mean? There is not a coherent answer in this collection. Some essays examine the history of gender ambiguity in all literature and end with trans lit; some essays talk only about literature by trans authors and eschews the cis; some essays ignore trans authors altogether, and simply talk about cis writers instead. One of the more baffling things about this collection is that, more than once, an essay will ponder for several paragraphs on cis literature, and then, instead of talking about trans literature, will bring up a trans television show or movie instead. In more than one essay, there arises this bizarre dichotomy where a literary cis text is juxtaposed against a visual trans text; suggesting, somehow, that a trans literature does not exist on the page, as the cis authors in this collection are thusly taken, but rather in the space of GENDER, which also happens to have books (and trans people) in it sometimes. This may sound familiar, and Chu offers us a cogent explanation of this process while spit-roasting the work of Karen Barad like a turkey on Thanksgiving:

In trans studies, which is so poor in theory to begin with, new materialist–style work somehow manages to take up a disproportionate amount of space while also, quite frankly, not making a lick of sense. […] Trans is doing zero theoretical work in this essay; it is employed here purely as an au courant garnish. […] Well, which is it, Karen? Is matter queer or is matter trans? Both, of course, because for her, like for most people who claim to be working in trans studies, queer and trans are obviously synonyms. If I sound angry about this, good. I am.15

And there we cut to the real core of the issue: “trans” in this volume is essentially a stand-in word for queer. This is not an omnibus of “trans literature” as it claims on the cover. Contrary to the assertions of the editors, there is a real thing that we can call and describe as “trans literature” – not because it reinforces a rigid definition of gender or transness, but because it arises out of the conditions of discrimination, marginalization, and community-based organizing through which trans people have struggled to write in the first place. Rather, if I had to give this book a title, it would be the Routledge Handbook of Queer Literature about Trans People.

This core of queer theory seems to manifest out of an approach that is nearly identical to the “queering the reading” movement of the 80s and 90s. In this approach, even if a text is not explicitly gay or trans, if the characters act or perform in a queer manner, then one can make a “queer reading” of that text that proposes new methods of understanding about queerness. This approach of “transing” the reading of various cis genres necessitates the inclusion of texts which are not written by trans people, a decision which is justified by Sharp in their introduction, which states the following:

When trying to locate trans literature as comprised only by authors known publicly to be trans, we risk assuming that there is a proper way to be identifiable as such: excluded are those who are “not yet out” as trans, whose gender variance is illegible to the dominant Western framework, who lived before the availability of “trans” as a category for self-description, or whose sense of gendered self remains opaque.16

This is super based. And I’ll admit – on my first reading of this text, I was like, oh, yeah, that makes sense! Where it begins to fall apart, though, is when we arrive at the texts we’re taking airtime from trans authors to include:

This Handbook also features chapters examining creative works by authors not known to be trans or with no explicitly “trans” characters. Some works seem at first glance to be entirely unrelated to common trans issues or experiences. While some might object to the inclusion of works by nontrans authors in studies of trans literature, as many of the contributors to this volume demonstrate, holding the “trans” in “trans literature” open allows us to approach trans issues from new vantage points. […] This approach further serves to unsettle assumptions as to “trans content.” What does it mean to include characters who do not appear to be “trans,” but who nonetheless speak to ideas of sex and gender relevant to trans enquiry? What should we make of works usually read as relating to other axes of oppression, but that demonstrate gender’s entanglement with race, class, disability, and sexuality? More provocative still are works whose formal or structural qualities offer novel approaches to trans theorization without having much to do with sex or gender at all.

Again, I know that this passage was written like this to preempt the commentary of people like me: random trans women on the internet complaining about the lack of trans representation in the book about trans literature. And again, I don’t want to contest that this is a fair approach. There is value in reading books by nontrans authors through a trans lens, and trans scholars should absolutely be able to make such inquiries without academic pushback. I’m not contesting their relevance; what I am questioning is how we ought to handle those texts and ideas in the context of a volume that, ostensibly, is about defining a field of “trans literature” and the various contestations within. I walked away from reading this introduction thinking – and maybe this was my first mistake – that readings of books by cis people and other non-trans queer folks would be organized in service of deepening and challenging our readings and understandings of trans literature. What I found in my reading was quite the opposite – many of these essays gave well over fifty percent of their airtime to literature by non-trans authors. And again; I want to clarify that I am paying specific attention to where novels were discussed; my expertise lies in this area, and it is the only domain where I have any sort of qualification to make such observations.

Nevertheless, I found novels by trans authors being used to deepen the readings of novels by cis authors as often as than the other way around. This is not inherently a bad thing, but I found that it consistently hampered the depth to which trans novels were discussed. This was only furthered by the deployment of one of my least favorite tactics in trans studies: the modular “trans-” or “trans*,” which can be affixed to any term it wants. Transgender, transvestite, transsexual – sure. But transracial, transnational, translational – all of this becomes transsexuality too. This is, I think, one of the arenas in which Susan Stryker’s fingerprints on this volume become the most evident. However floral or pretty the language used to dress it up, the rationale ultimately boils down to something very reminiscent of Stryker’s 2008 piece “Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?” with Paisley Currah and Lisa Jean Moore:

In seeking to promote cutting-edge feminist work that builds on existing transgender-oriented scholarship to articulate new generational and analytical perspectives, we didn’t want to perpetuate a minoritizing or ghettoizing use of ‘transgender’ to delimit and contain the relationship of ‘trans-‘ conceptual operations to ‘-gender’ statuses and practices in the way that rendered them the exclusive property of a tiny class of marginalized individuals. Precisely because we believe some vital and more generally relevant critical/political questions are compacted within the theoretical articulations and lived social realities of ‘transgender’ embodiments, subjectivities, and communities, we felt that the time was ripe for bursting ‘transgender’ wide open, and linking the questions of space and movement that that term implies to other critical crossings of categorical territories.17

And this again echoes Trish Salah’s argument that instead of producing a minority literature, trans literary scholars need to theorize a minor literature.

We must reemphasize our criticism from our first essay – focusing on the corpus of literature written by trans people is not an act of minoritization, but a method of inquiry grounded in the real, material conditions and discrimination unique to trans authors and the books which they produce. I have always found Stryker’s language of “exclusive property” to be in extremely poor taste. From a standpoint of class, trans authors are not only poorer, less likely to make a living wage off their writing, less likely to find a publisher, less likely to become a midlist author, less likely to be reviewed, and less likely to be critiqued than our cis counterparts – half the time we’re barred from the damn industry altogether. Property – what property? The discrimination in publishing against trans people was so severe that we essentially had to build our own miniature publishing industry before the conventional publishers started paying attention to us. How many trans authors have been homeless? Sex workers? Working multiple other jobs to pay their bills? It is an absurdity to claim that by discussing trans books, the trans academic will be minoritizing themself. We’re already minoritized – that’s the reason we need more trans academic scholarship in the first place! Does it become a stain by association? Is it slumming it in the “ghetto” of trans literature to want to talk about trans books that don’t have a golden cis stamp of approval on them?

Let me flip it around – by not discussing trans books, there will be a perpetuation of the minoritization of the trans author, who in all likelihood will continue to receive no attention from the cis academic. This rhetoric relies on an identification between the class status of the trans author and the trans academic, and I cannot help but feel that in the pursuit of “bursting ‘transgender’ wide open” and playing liberal respectability politics by taking an agnostic approach to trans authorship, the trans academic has staked their priorities as one above the other.

This anger, my dearest reader, arises out of the observation that even in the one place which ostensibly purports to center trans literature, there seems to be a relentless drive to play it at equal hand with cis literary production. Ultimately, this comes down to the difference between equality and equity. The Routledge Handbook for Trans Literature is very careful to take an equal amount of everything – equal mediums, equal genders, equally trans and not. But in doing so, it portrays the field of “trans literature” as a two-sided coin, where both cis and trans authors have treated their transgender characters in a manner that can be studied similarly – and often uncritically – as analogous to each other. This both-sides approach is frustrating not in the least because it seems to sugarcoat the fact that cis books about trans people and trans books about trans people are not treated the same in the publishing industry, have never been considered equals in the eyes of the literary gatekeepers, and indeed have quite often seen their cis incarnations weaponized against their trans cousins.

It’s telling that despite many of articles in this volume citing at least one Gender Novel – AKA a novel by a cis or non-trans queer author that uses the trans body either as a symbol of suffering, a sexual object, a perversion, or otherwise a vehicle for the author’s particular critiques of the state of the world – only two articles in the entire volume cite Casey Plett’s 2015 critique “The Rise of the Gender Novel,” which laid out in unflinching terms the harms which these novels do to trans communities.

And – wouldn’t you know it – many of Plett’s critiques of the Gender Novel seem eerily similar to our critiques of the interchangeability of trans literary criticism:

All of which is frustrating but unsurprising. What’s surprising, even flat-out weird, is how alike all the protagonists are. Their lives unfold almost identically: they grow up in unsupportive families; their fathers are domineering or distant; their mothers are kind but frail. When they come of age, they leave humble hometowns to find new lives in the big city. They rent crappy apartments, work menial jobs, detach from their families, and fall in with crowds good and bad. Most of them are physically or sexually brutalized. […] These novels aren’t just clichéd by the standards of transgender literature—they’re clichéd by any standard. Meanwhile, the sections of these books that don’t deal with gender variance are often vivid and fully realized, particularly in Middlesex and Moving Forward. It’s not that Fu, Winter, Mootoo, and Eugenides aren’t talented writers. So what does it say that four very different authors set out to write four very different people—and came up with the same non-person? And why are cisgender readers so moved by such one-dimensional characters?18

I stated in my last essay that I believe the field of trans literary criticism is lagging about a decade behind the field of trans literature. Fitting, then, that approximately nine years and six months after the publication of this article, I’m sitting here asking the exact same questions about trans literary scholarship.

All of the faults and short-comings of this approach are best encapsulated in the second article in this volume, “Performativity and Trans Literature” by Alexa Alice Joubin:

Trans as method, a systemic method of interpreting the performativity of speech acts, serves disempowered communities rather than services compulsory normativity because I acknowledge the space inhabited by atypical bodies while avoiding replicating the miscategorization of trans individuals. Performativity opens narratives up for new interpretations that attend to speech act. Attending to performativity enables us to expand the scope of trans literature, to attend to the materiality of transness, and to turn gender variance from merely what is mistakenly seen as a plot device into an integral part of embodied mimesis. This view of trans literature can be more inclusive and demonstrates that transness concerns everyone, especially when there is already an increasing number of documented incidents of cis women being harassed for “not looking feminine enough” (Mahdawi 2023). By trans inclusiveness I refer to conscientious and intentioned engagement with transness rather than a superficial form of encyclopedic comprehensiveness that essentially serves as euphemism for institutions such as schools, workplaces, and literary canons. It is not truly inclusive if we reduce trans theory to a simplified extension of existing gender theory.19

This is, once again, a passage that I nodded along to the first time that I read it. But there’s a crucial flaw here upon which everything else in this volume turns: Joubin, like most of the other scholars in this book, isn’t thinking about trans literature when worrying about minoritizing the field; she’s thinking about trans scholarship. Read that last sentence again – trans theory is what these scholars are worried about marginalizing. It’s the same story as it was with Susan Stryker fifteen years earlier – the trans academic is more worried about their place within the academy than they are about accurately representing the lived and textural positionalities of trans writers and trans texts without it. This whole argument, the whole premise of trans as method, arises out of an anxiety that persists within the (usually white) trans academic – an anxiety of exclusion, of losing work, of not getting reviews and citations and tenure and by-lines. And, well – it’s not an unfair anxiety. Like I said at the beginning of this essay, there has not been a singular piece of secondary scholarship produced about this handbook within or without the academy.

But let’s not cut teeth. This has nothing to do with the situation of the trans writer, and everything to do with the situation of the trans academic and their desire to appease and find acceptance among their cis literary colleagues. Don’t get me wrong – I want there to be a place for contemporary scholars of trans literature in the English department. Hell, there’s a world where that’s my job in a decade. But this isn’t good scholarship, it doesn’t accurately represent the work of trans novelists, and most importantly, it’s terrible class praxis.

Don’t take my word for it, though. Let me walk you through how this ‘trans as method’ approach pans out for the trans novel in a sustained body of critical scholarship, and why this turns out to be such a dismal reality for the trans writer.

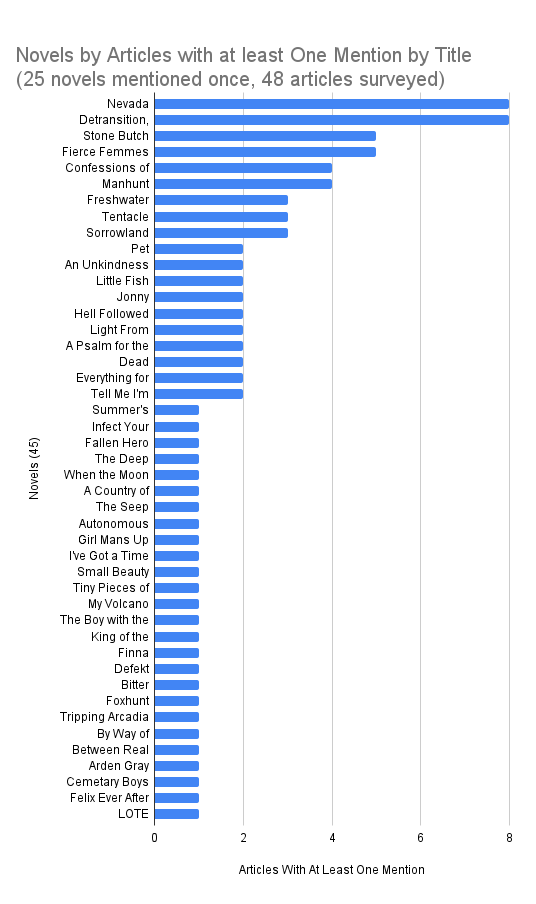

Novels in the Handbook by the Numbers

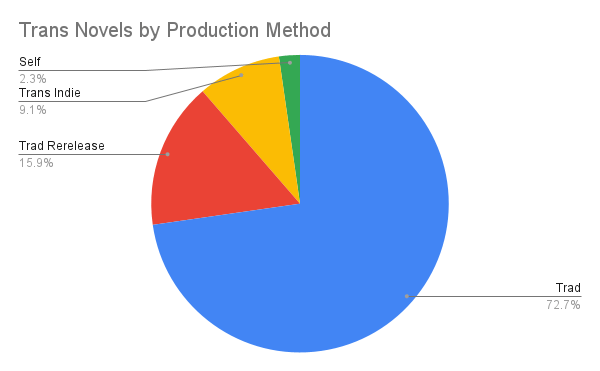

What I’m about to show you is a graph of every trans novel discussed in the Handbook, according to the numbers of articles it was featured in. Keep in mind that these are mentions, not thorough discussions. Moreover, the novels that were discussed more often tended to be the ones that got in-depth discussion. Nevada, for example, received at least one paragraph of analysis for 7/8 times it was discussed. A large chunk of these books were only mentioned in passing. There were 45 total novels by trans people discussed; Detransition Baby, Nevada, Stone Butch Blues, and Fierce Femmes were discussed more often than 25 of the books on this list were mentioned – over half.

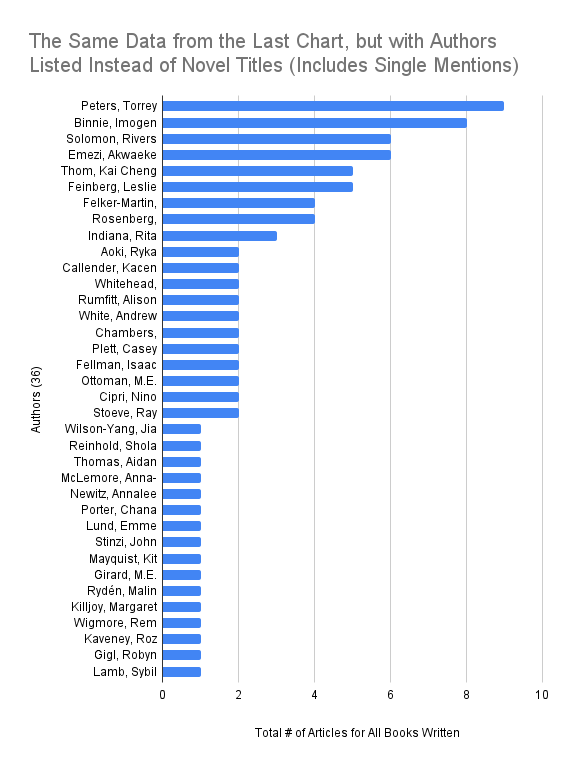

I want to acknowledge both that many articles juxtapose the trans novel against short stories, poetry, film, television, and performance art by trans people. I also want to acknowledge that, on the whole, trans novels received more substantive discussion than cis novels. However, both of these truths belie some of the more startling imbalances in this corpus of scholarship. Firstly, even this graph, which already shows how lopsided the scholarship was, doesn’t really convey how often the essays in this volume repeat the same ideas and phrasings. For example, the selectivity of trans authors discussed becomes evident when you look at a graph of authors:

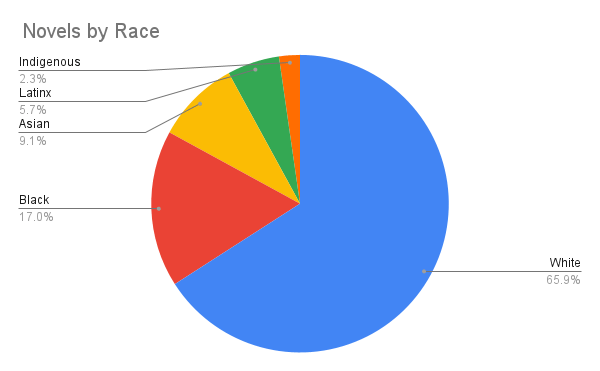

As you can clearly see, over a 523 page volume, just eight authors received over 50% of all discussion in cases where trans novels were discussed. But it’s not just a question of how many authors, but also of which authors – how they were chosen, and why. I would be remiss if I didn’t include some demographic stats about this group:

This is actually pretty good! Publishing skews heavily white, and this distribution maps fairly closely onto the racial demographics of the United States and Canada, where the vast majority of these books are written. However, what you’ve got to remember is that with a sample size of only 45 books, this is actually a very, very narrow selection of books by TPOC. That 17% of books from Black authors? That’s only four authors (and that’s with an entire chapter dedicated to “Black Studies and Trans Literature.” There are only three Asian and Latinx authors discussed. Joshua Whitehead is the only indigenous author, and he self-identifies as Two-Spirit, explicitly not trans, which means that he probably doesn’t even belong on this list in the first place.

But this is actually the least problematic of the demographics we need to examine about these authors. Let’s now consider, for example, the graph of which decades were most heavily represented by novels discussed:

I know that there wasn’t a lot out there before Nevada. But the fact that only two books from before 2013 were so much as mentioned is a completely embarrassing display of recency bias from this collection. Guess how many trans-authored novels from before 2013 Trish Salah mentioned in “Transgender and Transgenre Writing?” Six novel in twenty-one pages. The Routledge Handbook manages two in five hundred and twenty seven. Let us be very clear that the handbook did discuss novels from before 2013 – and all of them were either novels by authors who never self-identified as trans or autobiographies. This omnipresent substitution is incredibly sloppy, and it’s clearly not because the authors weren’t aware of earlier texts; scholars mention trans people who wrote novels before Nevada many times. But for a layperson reading this book, you could be excused if, apart from Stone Butch Blues, you thought that Nevada was the first novel ever published by a trans person. Mentioning an author off-handedly without even the name of their books is not a sufficient record of the cultural output of trans people before our contemporary age.

I think the most important statistic we can pull from this survey is not a question of what books were discussed, but rather how they were published:

For the purposes of this survey, “traditionally published” means “published by a cis publishing company.” “Traditional rerelease” includes books that were published in indie trans circles, then received a second printing from a cis publishing company. This category includes Nevada, which accounts for over 60% of its volume.

It’s hard to capture how poorly this depicts the reality of the publishing industry for trans people. Or, perhaps more accurately – for transfemmes. Those indie publishing stats? Every single one of those authors (save Joshua Whitehead) is a trans woman. As far as I could tell, every single novel by a transmasc or nonbinary author was traditionally published. But the bleakest statistic of all is that only two self-published novels were discussed in the entire volume, one of which was a Torrey Peters novella that’s getting a rerelease from Penguin/Random House in 2025, the other of which is an interactive novel that’s debatably not even a novel at all. As far as I can tell, the #1 factor that resulted in a book by a trans author getting discussed in this volume was their proximity and acceptability to cisheteronormative gatekeeping in the publishing industry. There was not a single book discussed in this entire volume that is “underground” in any meaningful way. This goes hand in hand with the exclusion of any book published in the West before 2013 except Stone Butch Blues – in 2013, the publishing industry suddenly decided the trans author was an acceptable client, and then and ONLY then does the academic record of trans novelists begin. Even in articles that purported to discuss “underground” literatures, like the “Fanfiction” and “Radical Novel” articles, I was astonished by the sheer lack of discussion about anything deserving of the term.

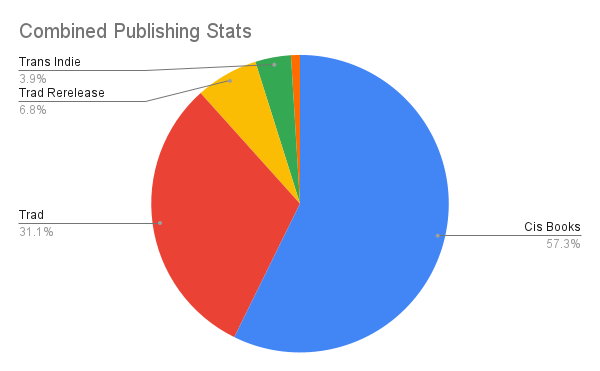

All of this is, of course, without factoring in the skew produced by the “trans as method” doctrine these articles adhere to. So let’s factor in what these stat distributions look like when we include the cis novels that were also discussed in this book. Note that these are just the books where the author was cis AKA Famous Novelists and their ilk – I left out some ambiguous edge cases so as to not skew the data:

When you read a lot of literary criticism, you find a lot of “survey” paragraphs that mention a bunch of books off-hand, but don’t go into detail. While they may seem superfluous, I actually think they’re super important when you’re talking about a historically marginalized literature. There are books I’ve read for this project where the only reason I was aware of them was because of a survey paragraph. One of the biggest problems with this book is that, in those survey paragraphs where novels are named, it is almost always without exception a list of novels by cis authors, even if the rest of the article concerns trans texts. This produces a siloing effect where, even though the discussion of trans texts takes up the majority of the airtime, one walks away with the distinct impression of their isolation and exceptionalism, even when there are very obvious examples to the contrary.

To get a sense of how much more diverse the selection of cis authors was, we can compare against the trans novel sample size. Eighty-three (83) novels by cis people were mentioned at least once in the Handbook, compared to forty-five (45) novels by trans people. When looking at the authorship stats, there were significantly fewer cis authors who had multiple texts discussed (83/78 = 1.06 novels per cis author; 45/36 = 1.2 novels per trans author). The eight most discussed cis authors received only 27.4% of the total discussion, as opposed to 53.3% for the trans authors. Considering that the ratio of cis novels mentioned to trans novels mentioned is about 2:1, this means that actual discussion of trans books outside of a select few cis-approved authors is severely constrained within the book. And once again, it must be emphasized that this compression has a disproportionate effect on the most marginalized elements of trans literature. Let’s take another look at the publishing graph with cis novels factored in:

So there you have it – with cis books factored in, less than 10% of this volume is dedicated to the trans indie publishing phenomenon. Of that airtime, the majority is dedicated to Nevada and Fierce Femmes. See that tiny little orange sliver? The one that’s so small that Google Sheets didn’t think it needed a label? That’s self-published novels. The sum total of time spent in this book discussing self-published trans novels is less than a single page.

When I spoke about “mythology” in my first essay, it’s easy to think that’s an airy concept that isn’t represented in the literary criticism I’m discussing. No. The mythology is produced by a series of decisions on the part of the academic – often subconscious or informed by a lack of access or education – to talk about some books and ignore others. It is also produced by the fact that this volume seems to pay little attention to the developmental history of trans publishing, and focus instead on individual books cherry-picked by their applicability to traditional literary scholarship.

None of this data accurately captures what was erased from the literary record, either. We don’t get any sense of the tropes or themes of 20th century fiction by trans people – only the vaguest suggestion that they might have existed. I was truly shocked that the “Fanfiction as Trans Literature” article did not cite a single fanfiction of any sort, let alone one written by a trans person. Taking this in view of the absence of analysis of self-published trans literature, AKA the majority of everything that trans people have ever managed to publish, it leaves the distinct impression of an academia reassured in its most flaccid instincts. This is how a “canon” of literature is produced – through the grave repetition of a small elite cadre of texts at the rigid expense of an accurate or wholesale survey of the genre and industry. Reading this text is like watching in real time as books like Stone Butch Blues, Nevada, Detransition, Baby, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, and Manhunt begin to form the rock-hard underbelly of a transliterary canon, one both all-encompassing in its polymorphism and beyond a historically grounded analysis of their production and development. All in all, it leaves a sour taste in my mouth.

Overall Thoughts

Reading this handbook has confirmed many of my worst fears about the current trajectory of transliterary academia. Unless you’re specifically looking for scholarship about “canonical” trans texts, you’re not gonna find much information about trans authors beyond what’s already readily available on the internet, and you risk walking away from the Handbook with a worse understanding of the current state of trans writers in publishing than you began with.

The Academy has long played power broker and gatekeeper to the mantle of the literary legacy. Much of what we now think of as the “classics” or “the Canon” are the products of universities like Cambridge and Oxford producing sets of every book they think worthy of the title; in other words, the academy as a publishing company rather than a observer of historical or material truth. The trans academic seems to be perilously teetering on the precipice of reproducing this ancient power structure within their analysis and work. And make no mistake – producing this volume will have a reverberating effect that echoes back into the field of trans publishing. A transliterary academy that fails to grapple with the nuance, depth, and complexity of a marginalized literature is part of a broader historical force that will inevitably flatten those literatures of their interesting features, before inevitably forgetting them altogether.

It is my earnest hope that in the future, the trans academic will take up more trans books and authors in their study, that they will engage with the trans author communities to better understand how and why those books were produced, and that their scholarship might thusly play an invaluable role in the preservation of our literary histories. For now, though, as Travis L. Wagner observed earlier, the Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature‘s assessment of trans literature as a genre provides its trans reader with little more than a fiction.

- Jones, Kassi. “Dr. Douglas Vakoch.” 2021. Digital JPEG. Wikipedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dr._Douglas_Vakoch._Credit_to_Kassi_Jones.jpg ↩︎

- Romberger, Julia E., and D. Vakoch. “Ecofeminist ethics and digital technology: A case study of Microsoft Word.” Ecofeminism and rhetoric: Critical perspectives on sex, technology and discourse (2011): 117-114. ↩︎

- Stryker, Susan. “Introduction.” In Transecology: Transgender Perspectives on Environment and Nature, ed. Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2020. xviii. ↩︎

- Transgender India: Understanding Third Gender Identities and Experiences, ed. Douglas Vakoch. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022. ↩︎

- Sharp, Sabine. “Introduction.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 4. ↩︎

- Anae, Nicole. “Culture and Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 21. ↩︎

- Wagner, Travis L. “Archival Speculation and Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 72. ↩︎

- Ibid, 80. ↩︎

- López-Medina, Esteban F. and Quinterno, Mariano H. “Teaching English as a Foreign Language and Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 208-220. ↩︎

- Schlotterback, Eamon. “Life Writing as Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 269-279. ↩︎

- Sharp, Sabine. “Science Fiction and Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 311-320. ↩︎

- Deininger, Michelle. “Young Adult Literature as Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 376-386. ↩︎

- Hammes, Aaron. “Minor Literature as Trans Literature.” In The Routledge Handbook of Trans Literature, ed. Sabine Sharp and Douglas Vakoch. New York: Routledge, 2024. 448-457. ↩︎

- Chu, Andrea Long and Drager, Emmett Harsin. “After Trans Studies.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 6, no. 1 (2019). 110. ↩︎

- Ibid, 111-112. ↩︎

- Sharp, “Introduction,” 4. ↩︎

- Stryker, Susan, Paisley Currah, and Lisa Jean Moore. “Introduction: Trans-, Trans, or Transgender?” Women’s Studies Quarterly 36, no. 3/4 (2008): 11-12. ↩︎

- Plett, Casey. “Rise of the Gender Novel. The Walrus, March 18th, 2015. ↩︎

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.