Welp, guess who just got another review censored by Patreon!

Unlike my review of When The Harvest Comes, which contained excerpts of the book depicting CSA, my latest review of Inori’s 2025 light novel Homunculus Tears merely mentions incest and underaged sex. Apparently this is sufficient to label the book as “sexually gratifying work.”

Yep. That’s it. Just mentions it.

Given that the content is way less delicate than last time, I’ve decided that instead of waging a whole battle with Patreon, I’m just gonna publish the review here. As with most of my Patreon reviews, this is a shorter piece than what typically goes on the main site – my primary goal is to ensure that my readership can still access my thoughts without censoring the meat of my critique of the book.

I’m pissed, but I refuse to give them my emotional labor today.

If you want to see all of my reviews, consider supporting me on Patreon starting at $4 a month, where you can find me at The Transfeminine Review.

This article was made possible by our wonderful Sponsors! If you want to contribute to essential transgender journalism like this, then please feel free to go support our work on Patreon – your contributions help us keep Academic Quality Scholarship 100% free and available to the general public.

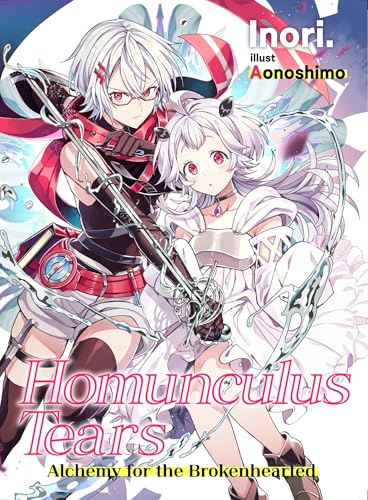

Homunculus Tears: Alchemy for the Brokenhearted by Inori

Date: 4/26/25

Publisher: Self

Genre: Light Novel, Fantasy, Post-Apocalyptic, Yuri

Website: https://inori-0.fanbox.cc/

Bluesky: @inoriiltv.bsky.social

Purchase: Amazon

[TRIGGER WARNING] THIS REVIEW DISCUSSES SUICIDE, ABUSE, AND INCEST. PLEASE READ WITH CARE.

I can’t tell you about this book without talking about how powerful its themes and message are, so we’re gonna start there with this one.

I’ll let Inori do the explaining:

The theme for this novel was anti-anti-natalism. That’s quite the academic-sounding word, but really it just means that this was a story about people who wish they weren’t born and want to disappear (or to put it more bluntly, who wish to die) and how they challenge and overcome those thoughts.

The debate over whether or not euthanasia should be legalized in Japan has rapidly intensified as of late. Some other countries have already implemented it, and more and more people seem on board with the idea by the day. Of course, I understand why those in medical pain might choose assisted suicide from a quality of life perspective, and I hope legislation and implementation is as smooth as can be there, but I can’t help but think that many of the people of Japan who seek euthanasia seek it for different reasons. It’s my belief that those who feel defeated by life and wish for a way out have a truer, more sincere wish deep down that they just can’t voice. That’s where I drew the inspiration for this novel from. To all those who have the misfortune of wishing they hadn’t been brought into this world, I hope the message in this novel could reach you.

Maha is an alchemist who’s been fighting a hopeless war all her life, and the entire crux of the story is about her suicidal ideation and PTSD. Her titular alchemist powers rely on a link with the book’s narrator, an ephemeral once-human alchemist who’s essentially been transcended into the akashic records, and in order to use them, she has to surrender her memories, a power she abuses to avoid feeling her trauma.

The idea of “akashic records” are a term from Theosophy, a new-age American spiritual occult tradition that interpellates Sanskrit terminology from Hindu and Buddhist cosmology, but in this story, it frankly reads more like it’s been lifted from Genshin Impact and Sumeru’s Akasha.

Note: It’s been correctly pointed out to me by others who have broader anime knowledge that this is a fairly common anime trope – I mostly watch romance and slice of life stuff, so mea culpa on that one.

The plot begins when Maha’s absent mother Diriyah creates a homonculus named Ruri, who’s essentially a replacement for Maha, leaving her feeling unmoored without her life’s purpose. Both Maha and Ruri have been trained/created to safeguard a spell that can be used to end the world, a thinly veiled suicide metaphor, and fight against a largely metaphorical horde of ‘demons’ seeking to access it.

Between the nebulous relationship between Maha, Ruri, her mental companion Metako, and her rival/antagonist Ney, the main quartet of characters in this book feel less like individuals and more like a psychological portrait of a plural person, or the mental headspace of someone experiencing severe dissociative or post-traumatic symptoms. This atmosphere is fleshed out through the themes of amnesia and depression; the oppressive subtext of Diriyah’s abusive parenting; and more broadly the sparseness of the text.

Ruri is a literal re-embodiment of Maha, created from her ‘sister’s’ blood, and as such provides a perfect foil for Maha’s suicidal ideation. As she comes to care about Ruri, Maha becomes increasingly more alarmed to see her own suicidal thoughts reflected in her homonculus. It’s through this realization that she can’t bear to see Ruri die that she realizes that others feel the same way about her, giving the whole psycho-sexual narrative a powerful theme of self-love and healing from depressive tendencies.

I say all of this to indicate that this book is interesting. It has a really compelling and contemporary set of themes, and it has a lot to say about its core message of suicide and healing. Moreover, there’s some really interesting perspective play by writing the narrative in a typical third-person limited manner, but framing that as from the perspective of Metako, who offers a peculiar lens on the story. I think this choice works specifically because it allows us to see Maha’s suicidal ideation without ever forcing the reader into that perspective. For the whole book, even when Maha is at her lowest, we always see her life from the perspective of someone who wants her to get better and understands her interiority, and I think that’s really powerful.

All that being said.

The translation for this book is, to put it bluntly, terrible. It completely lacks the prose quality or clarity of past Inori books I’ve read – for example, compared with I’m in Love with the Villainess, which came out six years ago, this feels like a sloppy project done by amateurs in their free time, not a published product. It’s worse than some of the fan translations for manga on sites like Mangakakalot, and that’s saying something.

If it were consistently bad, it would be a lot easier to handwave off as an unfortunate detriment, but regrettably it’s also unevenly bad. There are passages that come across really well, and others that are obtuse and uncommunicative. There are chapters with perfect grammar, and others that have basic grammar errors like dropping articles.

Frequently, I found myself wishing I could read the original Japanese, because there were places where you could tell that the prose was meant to mean something or carry some weight, and it was impossible to parse the original intent.

It’s worth noting that this is Inori’s first time self-publishing, and apparently the English version was released at the same time as the Japanese version:

This novel involved a number of firsts for me. One of which is the fact we are doing a simultaneous release together with the English, Spanish, and German translation of the novel; another is the fact that I’m self-publishing. Not going through a publisher means losing a lot of advertising potential. The themes in this book are more of the kind of thing you might prefer to keep close to your heart instead of sharing publicly, but if it’s all the same to you, it would be of considerable help if you could share your thoughts on this book online to help get the word out. Wouldn’t it be amazing if we, together, could make this novel a big hit with word of mouth alone?

This does offer us an explanation, but I’m left with the sense that the translated versions of the book may have been rushed for the global release. An extra two or three months of polish on the English translation would have gone a long way.

Another major issue I had were the more gratuitous tropes of Japanese anime humor. There is a consistent throughline where the main antagonist Ney is referred to as a ‘loli,’ which is not only uncomfortable, but also confusing given that Aonoshimo’s illustrations make her look significantly more mature than Maha. Additionally, for a fifteen-year-old protagonist, Maha’s characterization strays far too close to ecchi schoolgirl themes at times. Our narrator Metako, who is fully an adult, spends basically the entire book making sexual comments about how Maha should get into relationships, and while I’ve engaged with enough anime and manga to recognize this as a stereotypical genre trope, it’s still unsettling to me.

Furthermore, the book seems deeply vested in ambiguity about how, exactly, we’re supposed to read the relationship between Maha and Ruri. One chapter they’re sisters; the next chapter they’re wives. They share blood and a mother, yet everyone seems to ship them. But they’re not technically related cause Ruri isn’t human, I think.

Is that incest? I’m like, 90% sure that’s incest.

The translation quality and ecchi tropes are a shame, because there’s a really powerful book about mental health and suicide buried under all of it. But in its current state, I just can’t see myself fully recommending it.

6/10

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.