Last night, I found my community embroiled once again in a debate (a rather lopsided one) about the permissibility of AI covers for self-published fiction. The debate had started during one of my regular dumpster dives through the simulacra trash fire of the Kindle Unlimited marketplace, where I had found a number of tantalizing (and horrifying) little goodies to share with my wonderful readers. Among them were a number of flagrant examples of AI art, ranging from very obvious to subtle, the latter being the topic that sparked the debate.

I have a policy that I do not read or cover books that use AI in any fashion. But that wasn’t always the case. Back in 2023 and early 2024, before I gained a big platform and realized how evil the tech world had become these days, I would absolutely have read a book like this debut novel from Ana Edyn.

Here’s another fact – given my history with AI-influenced fiction, I probably would have panned it.

Across all of my rated books, some of the lowest scores I’ve ever given have been to slop with AI-generated covers from authors like Lilly Lustwood and Nikki Crescent. Both of those authors are very much still putting out regular fiction – but I haven’t covered a book from either of them at all in 2025.

My stance against AI now is an ethical one, and that’s not the point of this article. Rather, the question I want to pose has more to do with the quality of the books in question. When I look at a book with an AI cover, I know immediately that it’s probably not going to be very good. 90% of the time I’m correct.

As a critic with a large platform, should I read the book anyway?

The reason I sparked this AI debate in the first place was because, after a run of very good books, I had been gripped by the unsettled feeling that I was reading too many good books. Part of that is the nature of my current project – I’m writing a recommendations list, of course I’m gonna be hunting for good books. But I have this gut sense that it is not only productive but essential to intersperse my prestige readings with slop; to vary the quality that crosses my desk; to write reviews not only to the best of transfeminine literature, but to the worst of it too.

Let me try to quantify my argument here. This January, I posted an article titled “Bethany’s Top Ten Transfeminine Novels of 2025.” While the primary draw of the article was obviously the book recs, I also included some reading statistics at the top of the piece that are more pertinent to this conversation.

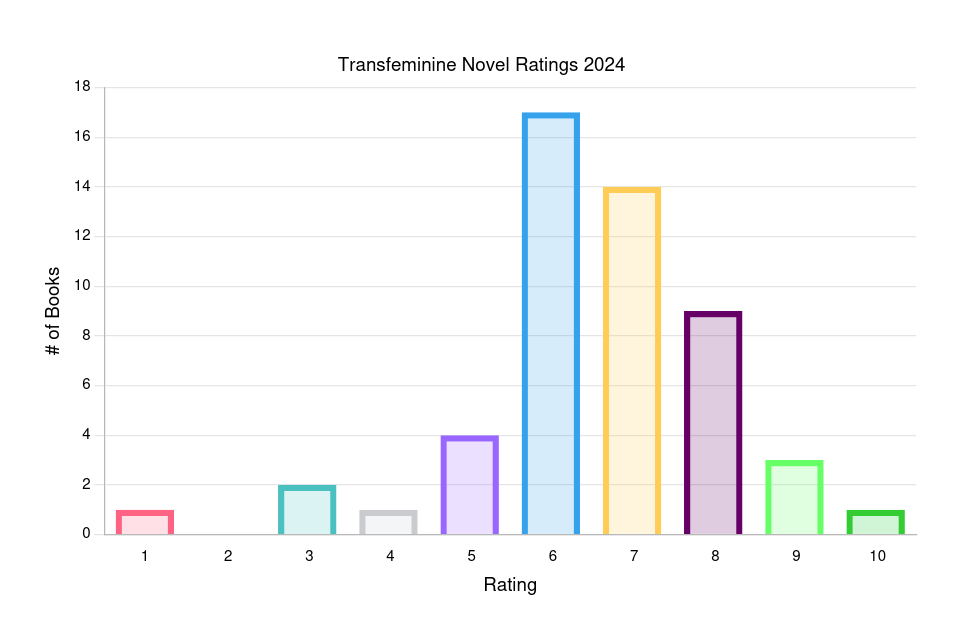

Just from a peak at this graph, you can clearly see that even in my critical system, which is more strict than a lot of reviewers nowadays, my reviews in 2024 skewed towards positive ratings. I wrote about about the statistical breakdown in that article:

My average rating per novel was 6.5/10. My median rating was a 7/10, and my most common rating was a 6/10. It should be noted that my average rating in 2024 was substantially higher than my average rating in 2023, which I think can largely be attributed to the fact that most books I read this year were recommended to me, not scrounged off the depths of the internet.

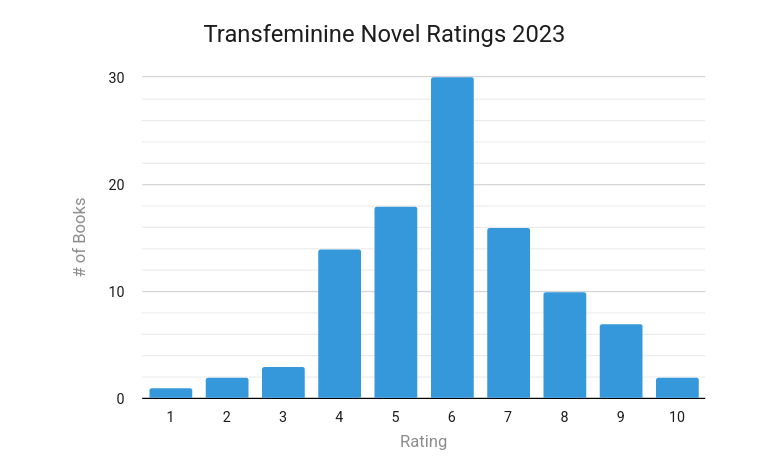

I didn’t actually show the stats for my 2023 reading in that article, but I think it’s important to go back and show them now.

In 2023, I read 103 novels (in contrast to the 54 I read last year). However, it should be pretty evident just by looking at the graph that I had a major shift in ratings between those two years beyond just the quantity of books. My average rating in 2023 was a 6/10. My median rating was 6/10, and my most common rating was a 6/10. Even though this might not seem like that big of a shift, the real story comes once you start to look at the broader statistical distribution of my ratings.

In 2023, my second most common rating was a 5/10, but in 2024, it was a 7/10. In 2023, I rated 14 books a 4/10 – but in 2024, I only gave that rating to one singular book.

I want to emphasize that this shift was not due to an overall industry-wide increase in the quality of transfeminine fiction. It was, rather, a product of the fact that the majority of my reading in 2023 was entirely based on my own research on the internet, whereas in 2024 the majority of my finished books came from book recommendations. By changing my reading process to favor the opinions of my online community, I had effectively added a layer of bias to my reading choices.

Now, bias in this sense is not a bad thing. The bias in question was a disposition to read higher quality literature – and that’s a good thing, right?

Maybe.

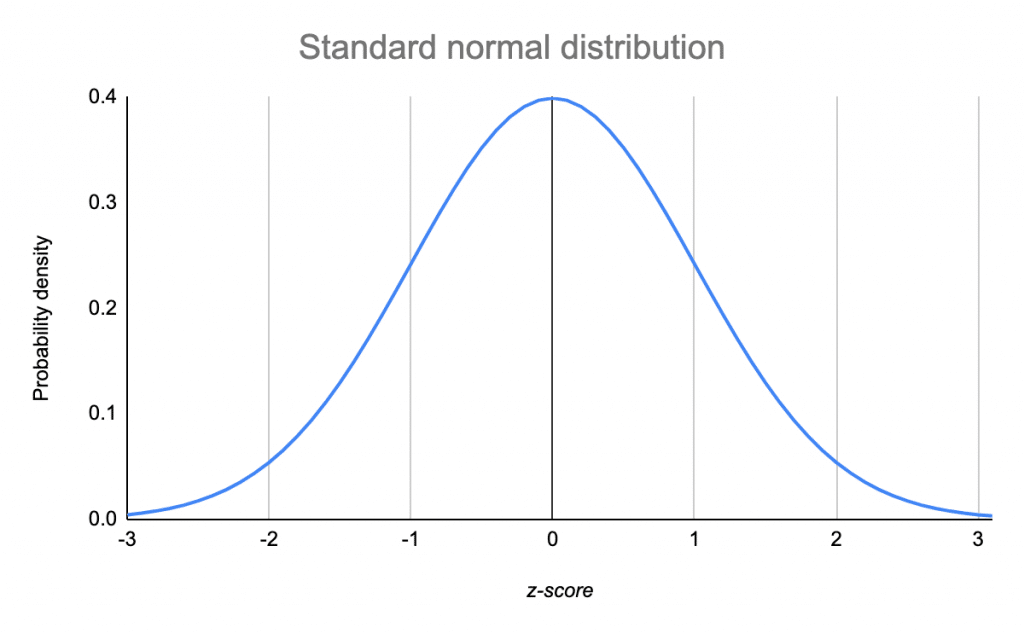

There are two concepts from statistics that I think are important for understanding what I’m trying to get at here. The first one in the idea of a standard distribution, i.e. the average statistical layout of a completely unbiased dataset. This is best recognized through the ‘bell curve,’ which essentially represents that an average dataset will have more responses around the middle and fewer at the margins, or ‘outliers.’

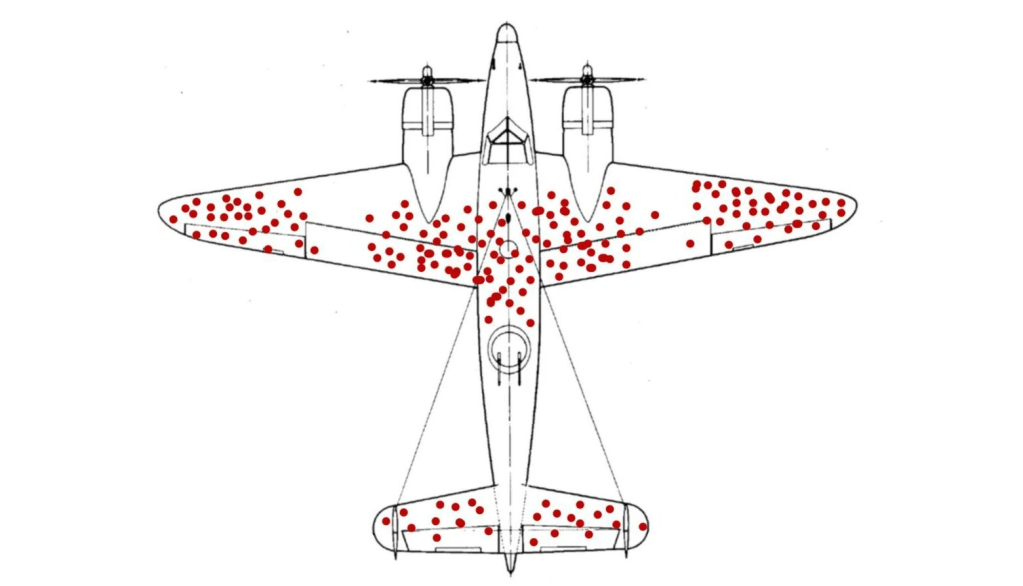

From the standpoint of a statistical analysis, my reading in 2023 hewed far closer to a standard distribution of quality than my reading in 2024 did. We can articulate this as bias to understand why that shift occurred, and I believe that can be attributed largely to survivorship bias.

Survivorship bias refers to a pattern recognized in war planes where all of the planes that survived the war had bullet holes in roughly similar spots. Scientists realized that the reason for this was because the planes that had been shot in the other spots – engines, etc. – had largely been shot down, and their pilots had not survived the war.

Nobody likes receiving a bad review – and there is a definite tendency when you’ve got as big a platform as I do to spark some level of defensiveness and avoidance among authors of bad books. I don’t hear about a lot of the year’s quiet stinkers! My wonderful readers, who also don’t want me to suffer, are significantly less likely to recommend a book they know is awful than a book that they loved.

As an aggregate source for transfeminine literature as a whole, I’m often the engineer inspecting warplanes after a long battle. I don’t see the planes that get shot down. I don’t see the books so rotten that folks think they don’t deserve mention.

On some level, I should like that, right? Fewer bad books to suffer through! But it also makes me sad, because I genuinely love reading bad books. I love reading books from new writers just learning the craft; I love reading breathless slop, I love reading hilariously awful prose. Hell, I even like reading the truly noxious stuff, if only to spare others the trouble.

It’s still a form of bias, and that bothers me.

Should Critics Be Biased?

Now, when you hear talk about ‘bias in criticism’ these days, it’s almost always on the matter of identity-based bias – racial, sexual, political, religious, and the like. And make no mistake, that’s a bias that I’ve been very conscious about in my work. I make a real effort to cover books across identity categories of all matter; authors from all over the world, of every profession and walk of life. While the bias I’m gesturing toward here is certainly not one of discrimination, I do think that looking at discriminatory bias can be useful toward elucidating what I mean here.

Why do we so strongly advocate for the removal of discriminatory bias from publishing? Aside from the obvious answers – equality, economic justice, representation – there’s a quieter issue of how the literary object is treated in the critical eye that helps to produce double standards and glass ceilings. When books by white men receive critical attention, it often comes irrespective of the actual quality of the book. What this means is that you’re just as likely to see a critic panning an awful book from a white man as praising a great one – and when you take an aggregate of review, the average will likely fall somewhere around the middle.

By contrast, books by trans women of color often only receive coverage when they are exceptional – exception, different from the norm. Because the baseline quality needed for critical attention is so much higher, there is a selection process that demands nothing short of perfection from trans authors of color, one which promises harsh consequences for failure. This is a self-perpetrating cycle – higher expectations means fewer reviews means fewer successes means higher expectations, leading to the self-enforcing norm that trans women of color should be allowed to publish less, and to expect nothing short of perfection when they do.

So the question of reviewing bad books is not exterior to the question of discriminatory bias – anything but. When the critic only selects the cream of the racialized crop, he is reinforcing systems of oppression that directly lead to fewer authors of color.

But I don’t want to only question this in identity category terms. My question is broader – does the critic in general have a responsibility to read bad books?

As I’ve motioned to here, it seems somewhat evident to me that a bias against bad books can often dovetail with a bias against books by marginalized authors. But I reject the notion that a bad book by a trans woman of color is qualitatively different than a bad book by a white man. I believe that anyone is capable of truly horrendous writing. I believe in a bad prose, a noxious allegory, an unreadable grammar, and an incomprehensible design that transcends any foolish division of human taxonomy.

My pressing question tonight is this: is reading terrible prose in-and-of-itself a lode-bearing part of the critic’s job?

My answer is yes, it is. And yes they should. Critics must read bad prose – not just because they stumble upon it, not just because they’re forced to read the latest memoir from a rich white man in a position of power, but with the full force of their mind and heart, enthusiastically, with a passion. It is no more extricable from the critic’s toolbox than critique itself.

Yes, critical bias against bad prose can often lead to an implicit bias against marginalized prose. It’s important to recognize that the ‘bias’ in question is not our critique of bad prose, which must be as firm and vicious as ever, but our choice to approach it in the first place. It’s a bias of selection, not interpretation. We must treat all bad prose with just indignation. But a bias against bad prose can also blind us to the true quality of the books we assess.

‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’ is a statement often conflated with something far more insidious – ‘Don’t judge a book by its business practices.’ AI is a business practice; it is a material choice, one that operates on theft, one that disenfranchises the author and the illustrator, one that hastens the degradation of our environment and culture. But labeling all bad books as ‘slop’ and confining them to the refuse bin of history is a business practice too. It is the business of traditional publishing houses to package their books in aesthetic covers and pretty dustjackets; to make them appear accessible, popular, well-regarded, important; to catch the eye from the street or the mall or the internet storefront, to draw a reader’s gaze on the shelf. The economic reproduction of literature relies on these marketing decisions, which themselves prey upon the biases and fickles of their readers. This, too, is a matter of business practices – it is good business for major corporations when critics refuse to give ‘unprofessional’ or ‘ugly’ self-published titles the time of day.

The critic has a duty to work against this prima facie approach to literature, precisely because it is the duty of the critic to critique the business of publishing with equal rigor as its products.

The bias I am concerned with isn’t just a bias against bad books – it’s a bias toward what kinds of bad books the critic ends up reading. More often than not, we’re ‘disappointed’ on the rare occasion we read a real stinker. It’s a letdown – but why? This is because even when a critic reads a bad book, it’s often because doing so was good business. Good business can be on the publisher’s end through successful marketing, or on the critic’s end through the accumulation of prestige, attention, or money through their reading choices.

But what critic worthy of the name only reads books when it’s good business? True criticism is often bad business for everyone involved – ruinous for authors and corporations, unflattering and dangerous for the critic herself.

I don’t trust a critic who treats her reading choices solely as a business practice, and neither should you.

Rejecting a prima facie criticism also means embracing the ability of bad books to surprise us. This goes both for seemingly ‘bad’ books that turn out to be hidden masterpieces, and for books that are far, far worse than they appear at first glance. You can’t know for certain until you’ve read the book, and you’ll deprive yourself of the experience if you’re never willing to try.

Beyond Entertainment

Beyond all of these considerations of bias, though, there’s a much simpler issue at hand: why should we bother to read books that aren’t enjoyable? Why should we make ourselves suffer with terrible fiction?

First off, the premise that all bad books are miserable experiences is false. I’ve read terrible books that were great fun, and excellent books that made me want to crawl into bed and watch paint dry. But there’s a deeper issue here about the value of literature as entertainment itself.

In this age of digital literature, there’s been a rise of thinking about art and artistic labor as ‘content,’ digestible packages for the idle amusement. While this isn’t nearly as new or original as many in our time seem to think, it is an issue that’s been exacerbated by shortform content, broken attention spans, and a glut of AI-generated slop flooding the market. In this sea of shitty low-effort content, it often takes a cognizant effort to tear oneself away from the slurry and focus on the ‘real’ art. What this produces in the ‘literary’ type is a tendency to disavow anything that so much as smells like low-effort content (again, not nearly as original a trend as the self-assured type might think).

Here’s a statement that might be radical in 2025: ‘bad art’ is still art, not content or slop. “But what about AI?” What about it? It demands that we interrogate the definition of art itself, and therefore here is mine: art is a practice, not a product.

Art is not something we consume. Art is something we do.

Artificially-generated ‘art’ does not fall beyond the purview of our definition of art because it lacks aesthetic merit. It has nothing to do with aesthetics. AI ‘art’ is not art because it is not something that the ‘artist’ has done.

Criticism is an art and a practice, too. It is not a passive commentary or a gestured commitment, but an active engagement; an enmeshment, a contract between critic, reader, and author. The critic’s labor – and it is labor, make no mistake – demands a full practice of literature, not just a partial one, and part of that work is engaging with bad books by authors who are themselves fully engaged with the practice of art. Without it, I see my critical work as incomplete. It falls upon us not only to articulate the successes of art but its failures and predatory tactics as well – its pitfalls, its denigration, its subterranean depths. It falls upon us to be able to recognize exploitation, wage theft, and plagiarism in all its forms; to advocate for the practices of working authors, to articulate the material relations of publishing and its varied business practices. Art deserves nothing less.

On these grounds, I reject the notion that bad art is merely ‘content’ or ‘slop.’ I reject the idea that bad art exists merely as entertainment, posed in contrast to an idealized ‘literature’ that touches on the true spectrum of the soul. Rather, I want to posit that the aesthetic quality of literature can both be found in its practice – how it was made – and its experience – how the reader moves through it. When we take art as a practice, bad art becomes just as important to understanding literature as good art. Because practice is a human universal; anyone can write, anyone can make art. To categorically reject bad art is to place aesthetic before craft – art as practice flips this old order on its head, and opens the doors for new modes of literary thought.

So yes – critics should read bad books. We should write about them too.

Good critical practice demands nothing less.

LAST WEDNESDAY: #14 – An Afternoon with Erica Rutherford

NEXT WEDNESDAY: #16 – 12 Chilling Books by Transfemmes to Read This Halloween

Join the discussion! All comments are moderated. No bigotry, no slurs, no links, please be kind to each other.