[TRIGGER WARNING] This article will be discussing DID and all of its various causes, symptoms, and impacts, including but not limited to abuse, childhood sexual assault, rape, incest, suicide, homelessness, and other forms of state and cultural violence against transfeminine and plural individuals. Please read with care, and take breaks if needed.

[DISCLAIMER] I’m not a doctor and none of this is medical advice. If you’re struggling with dissociative symptoms, please consult with a psychologist or a licensed medical professional for guidance, not me. This is media criticism and feminist theory, not psychological guidance.

[AUTHOR’S NOTE #1] As will be elaborated upon later in the article, there’s a very significant divide in the plural community between people who identify more with the “Dissociative Identity Disorder” diagnosis versus the demedicalized “Plural” label. I am writing this article from the personal perspective of identifying with both, and I will also be both discussing and critiquing both at various points. If I am using the words “DID” and “plural” somewhat interchangably, it’s because it A) reflects my personal experiences and B) is the most effective way to communicate the issue to a non-plural audience.

[AUTHOR’S NOTE #2] “Syscourse” between the endogenic and traumagenic plural communities is a discourse constructed around an ongoing debate about the causes and origins of plurality. For reasons that I will discuss extensively later in the article, I believe that this deontological (regarding the causes of being) framework is a fundamentally unproductive paradigm, and that activists are better served focusing on the social and material nature of pluralphobia in its various manifestations. The “DID” or “plurality” I discuss in this article will resemble the conventional understandings of the terms and issues as they manifest in common parlance. I do not care about the deontology of alterhood, and while I respect deontology’s importance to the endogenic and traumagenic communities, I have exactly zero interest in engaging on the topic.

- What is Dissociative Identity Disorder?

- Systemhood and Transfemininity

- The Transmisogyny of Popular Pluralphobia

- “It could be Multiple Personality Disorder”

- CORE_FAILURE

- Endogeneity, Syscourse, and the Plural Community

- System Accountability

- Conclusion

What is Dissociative Identity Disorder?

Transgender women (hereafter “trans women”) are estimated to comprise approximately 0.1%–0.5% of the overall U.S. population; however, trans women are at a far greater risk for experiencing physical or sexual abuse, and/or psychological distress when compared with other adult populations. Over the past decade, survey-based research with trans women has found reported rates of physical abuse ranging from 39% to 47%, and sexual abuse rates ranging from 50% to 59%.

-Kussin-Shoptaw, Fletcher, and Reback, LGBT Health, 20171

Transfemmes are no stranger to trauma, dissociation, and trauma disorders. As a population, transgender women and transfeminine nonbinary people (especially those of color and with other intersecting marginalities) are disproportionately more likely to experience sexual, physical, familial, and societal abuse, homelessness, incarceration, violence, suicidality, and a wide range of other risk factors and forces of violence. As a result, transfeminine people are at a disproportionate risk of developing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a disorder caused by exposure to traumatic events classified under the broader umbrella of dissociative disorders, AKA “mental health conditions that involve experiencing a loss of connection between thoughts, memories, feelings, surroundings, behavior and identity.”2 As the Mayo Clinic writes, “Dissociative disorders usually arise as a reaction to shocking, distressing or painful events and help push away difficult memories.”3 According to a 2017 study by Reisner et al. (which inexplicably specified FTM cases but not MTF), an astonishing 76.9% of individuals living full-time post-transition exhibited symptoms for a clinical PTSD diagnosis.4 What this indicates is that not only are dissociative symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress prevalent in transfeminine population, but also that a majority of individuals under the broader transfeminine umbrella may be suffering from a dissociative disorder to some intensity or degree.

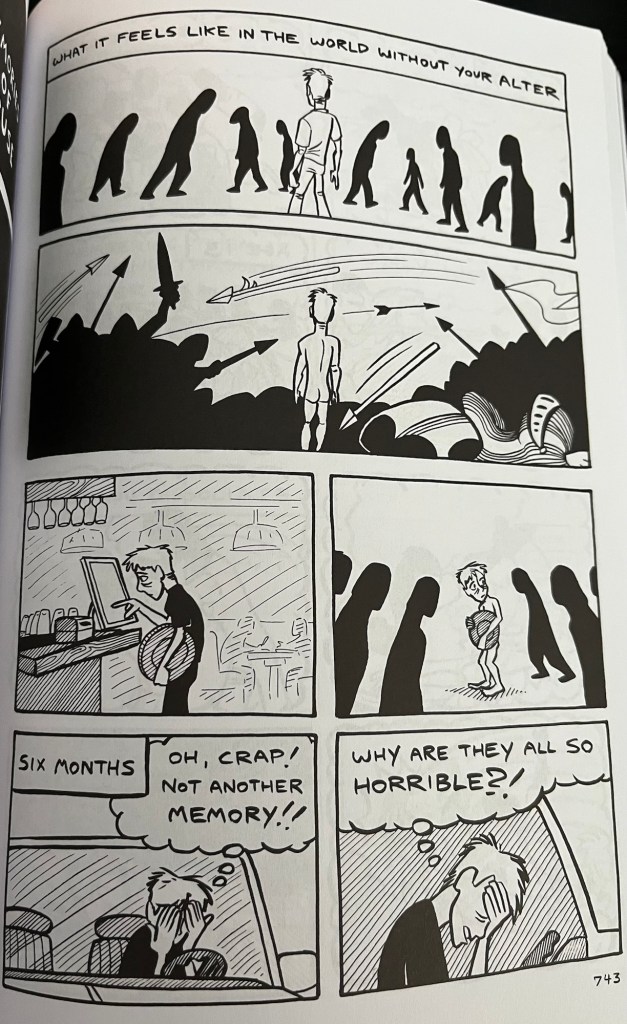

Dissociation is a term that gets cited often, and just as frequently remains poorly understood, even among those who experience it. WebMD describes dissociation as “an involuntary experience that occurs when you feel disconnected from yourself or your environment,”5 and you don’t need to have a full-blown dissociative disorder to have experienced it. Have you ever spaced out during news coverage of a major political event (think 9/11 or a major election) or a particularly stressful conversation with your family or your boss? Have you ever gotten distracted and lost track of time for a while? Any of that could be a dissociative experience. Dissociation is more than anything else a feeling – like staring at a blank wall or having trouble getting yourself to move. You feel distant, unfocused, dilute. Your head gets fuzzy or tight. Sometimes, it feels like you aren’t really living your own life, or like somebody else is moving or talking for you. In colloquial speech, people sometimes call this “being on autopilot.” It happens far more often than most people acknowledge.

Think about it this way. Your brain may work like a fancy biological computer, yes, but as with any computer, there’s hardware that makes the system run at all in the first place. Lots of miseducated critics and bad actors like to suggest that dissociation is a “choice” or a form of “laziness,” a piece of software that your brain has made an active effort to download and execute, and that dissociative symptoms originate within the mind, not the brain. This is not reflected by science or the clinical literature. Dissociation is better understood as a hardware issue, a physical rupture within one’s neurological circuitry between traumatic memories or experiences and their associated emotional responses. Recent research has shown that feeling dissociated may not just involve a disconnect within the brain, but also a synchronous mirroring of stimulus in the posteromedial cortex which can be repeated without its corollary mirrored stimulus (Vesuna et al. 20206). In layman’s terms, this essentially means that the feeling of dissociation, of removal from one’s body, can arise because the feeling actually occurs in two different parts of the brain, a literal removal, and further that in dissociative disorders, the “dissociated” response can then be repeated without the initial stimulus or action that caused it. Dissociative disorders arise when the individual experiences primarily this desynchronized form of dissociation as a recurring and impairing condition which can continue to resurface weeks, months, years, or even decades after that physical trauma response has stopped.

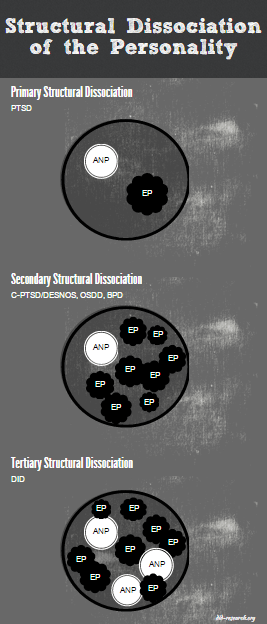

Most people will be aware of PTSD – shellshock, survivor’s guilt, the classic soldier’s burden. However, PTSD is only one disorder along a broader spectrum of dissociative disorders, which can be both less severe (Depersonalization/Derealization, Maladaptive Daydreaming) or more severe (Complex PTSD, OSDD, DID) depending on the individual circumstances. What underlies our contemporary understanding of all of these disorders, however, is what’s known as structural dissociation, a theory outlined by van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele in their 2006 book “The Haunted Self: Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization.”8 Research on structural dissociation has shown that contrary to many classical beliefs, the human mind begins not as a cohesive whole, but rather in a nebulous and fragmentary state – in essence, to be a young child is to be dissociated. Around the age of nine, the average human brain will fully cohere into a single unified whole. However, when someone experiences extreme trauma, this unity can be disrupted and dissociation will be caused as a result. With an individual with PTSD, a dissociated brainstate can emerge that sections off the emotions and sensations of a traumatic memory from the rest of the brain. This is the cause of a flashback. When an individual with PTSD experiences a flashback, their dissociated emotions assume temporary control of the mind, overwhelming all other stimuli.

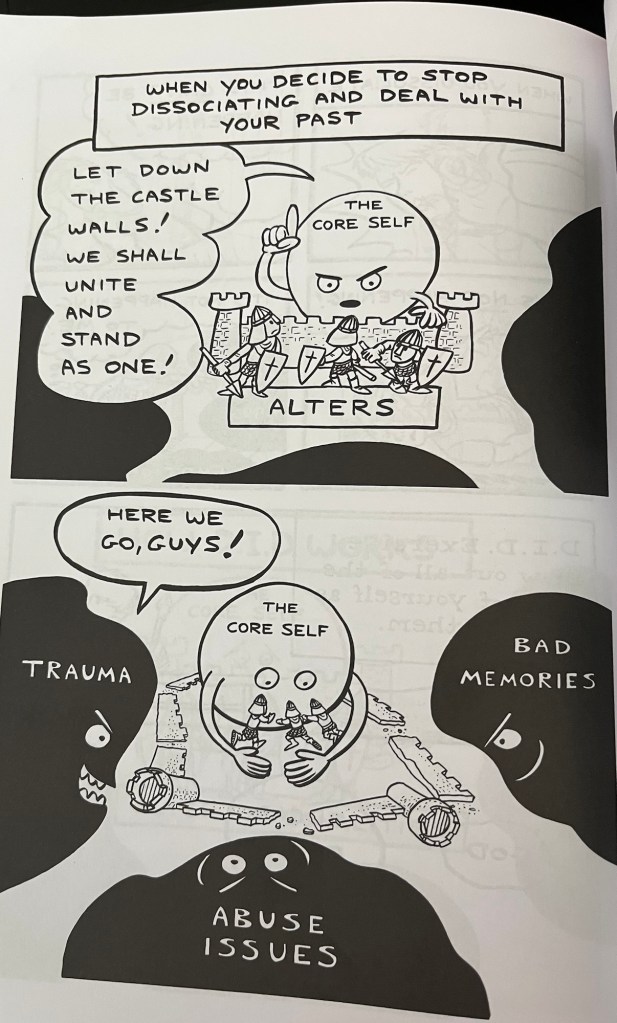

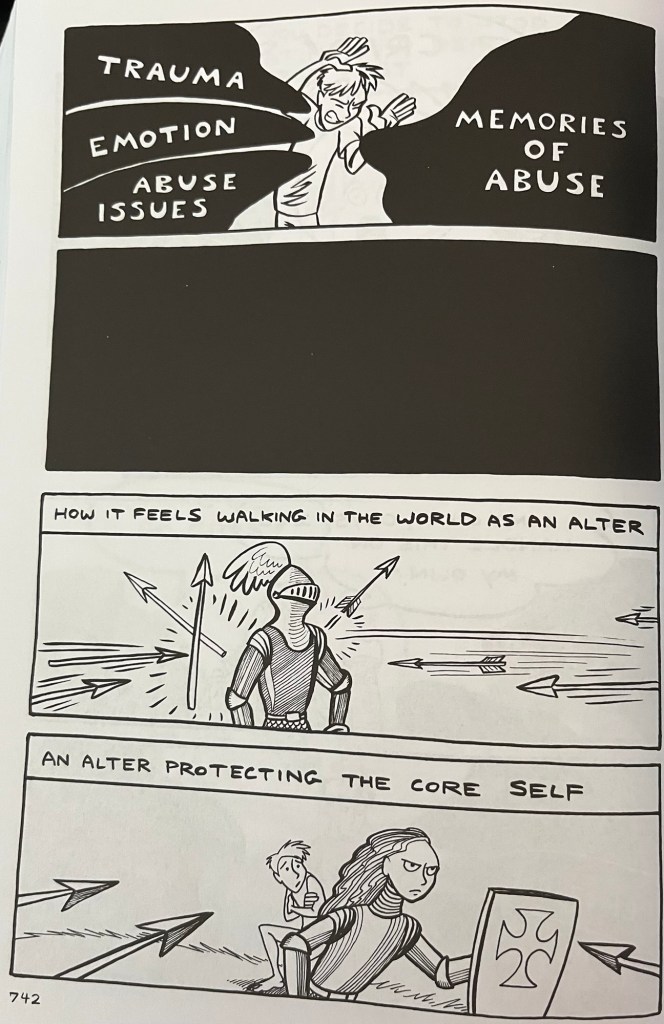

However, the most extreme disorder on the dissociative spectrum is somewhat different from most of its lesser incarnations. Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID, formerly Multiple Personality Disorder) is primarily characterized by the emergence of unique and distinct “personalities,” clinically referred to as “alters,” colloquially often referred to as “headmates.” The way I will be discussing them, however, is as individuals. There is an onto-mythology in the DID clinical sphere of an “original” or “core” alter who is the “real” person, and their “system” whose only purpose is to shield them from trauma. This is reductive and hearkens back to an era of clinical psychology that predates the structural model. In the past, the only viable treatment option for people with DID was a motion toward “integration.” This involved the “host” alter, AKA the “actual person,” attemping to reabsorb all of their “parts” and return to a “normal” brainstate, meaning only having a singular identity or personality occupying their brain. This can only be accomplished through extensive talk therapy, which has a typical prognosis of a decade, requires extremely specialized therapeutic care to be done properly, and ultimately occurs with the goal to “cure” the patient of their dissociative disorder.

Over the last twenty years, the theory of structural dissociation has challenged and unsettled the psychiatric common sense of the 20th Century. Under the current best theory, Dissociative Identity Disorder can only occur when a child is exposed to severe trauma before their mind has fully cohered into a single articulate identity, i.e. before the age of nine or thereabouts. Rather than having “shattered” the coherent mind into pieces, which thus must be healed like a broken bone, structural dissociation proposes that “alters” in DID “systems” (the collective noun often used to refer to all the identities in one body) were in fact never the same person. Rather, the core alters in a system, failing to come together into a single identity due to severe trauma causing dissociation in the young mind, each develop on their own as individual “identities,” “personalities,” or just “people,” depending on your preferred verbiage.

This can be extremely hard to conceptualize if you’re a “singlet,” or an individual whose brain cohered into a unified self. You feel like yourself! It’s one of the fundamental human truths – you don’t have the option to be anyone other than yourself. There’s a popular misconception of Dissociative Identity Disorder, then, that individuals with DID simply “choose” to become another person to escape from their traumatic histories. While this may be accurate in less severe cases, it’s not the whole story. What makes DID so fascinating and challenging from, like, a fundamental metaphysical lens is that each alter in a system has their own sense of selfhood. Katy feels like Katy when she’s out – so Katy must be the core personality, right? But when John’s out, he feels like John. Hell, he might not even know that Katy exists!

The point I’m trying to make here is that there’s real value in understanding alters in dissociative systems not as “personalities,” not as “trauma responses,” but as people who happen to live the odd experience of existing in the same body as other people as part of the same fragmentary consciousness. While this may be difficult for singlets to understand, it’s something that resonates deeply for many people living with Dissociative Identity Disorder and its various manifestations. Relationships with other headmates are often deeply personal (as one might imagine while sharing a body) and inter-personal, social by nature. Headmates are family, friends, colleagues, bitter enemies. It’s for this reason that many dislike the clinical language, and prefer the term “plural” to described their lived experiences as a person sharing brainspace with other people. Throughout this article I’ll be discussing alters in dissociative systems who have developed their own communities, cultures, and networks of care out of necessity and survival. Alters can have their own individual beliefs about their selfhood, origins, and ontological nature. In my experience, it’s rather rare to find a system where everyone in it does agree about those philosophical questions.

Systemhood and Transfemininity

Before we go any further, I want to be very clear: I am both plural and a trans woman. “Bethany Karsten” is an endonym – there are four of us who have been actively working to make this website a reality, each with our own strengths, weaknesses, and personal views on both transfeminine literature and the world. I’m writing this from the #ownvoices perspective as a plural trans reader who’s always searching for better plural trans rep in fiction, and it’s my hope that writing this article will help to elucidate our community, and how silent yet common we are in the broader trans community as a whole.

From personal experience, I’ve known dozens of trans women who are also plural. It’s important to understand that most alters have a unique inner presentation, not dissimilar from a physical body, represented within the mind. Alters can take on a wide variety of appearance traits, among which variant sex and gender are very much included. People squabble about this, but there’s a concept in transfeminism that’s very useful for understanding this paradigm, found through the work of Julia Serano in Whipping Girl:

Throughout this book, I will use the word trans to refer to people who (to varying degrees) struggle with a subconscious understanding or intuition that there is something “wrong” with the sex they were assigned at birth and/or who feel that they should have been born as or wish they could be the other sex. […] For many trans people, the fact that their appearance or behavior may fall outside of societal gender norms is a very real issue, but one that is often seen as secondary to the cognitive dissonance that arises from the fact their their subconscious sex does not match their physical sex. This gender dissonance is usually experienced as a kind of emotional pain or sadness that grows more intense over time, sometimes reaching a point where it can become debilitating.9

Alters much like singlets have subconscious sex. What differentiates them from a singlet, however, is that multiple alters in the same body may have different subconscious sexes, i.e., in a system with seven members, one could have two alters who identify as men, three alters who identify as women, and three alters who identify as non-binary. Alters may also transition internally – one of the unique privileges and blessings of a “headspace,” i.e. the mind palace many systems develop as an imagined space for alters to cohabitate, is that the materia of the physical body is often more malleable than in meat-world (though less so than one might think or expect). It’s much easier to be gender-fluid as an alter in headspace than a physical person.

This can get confusing.

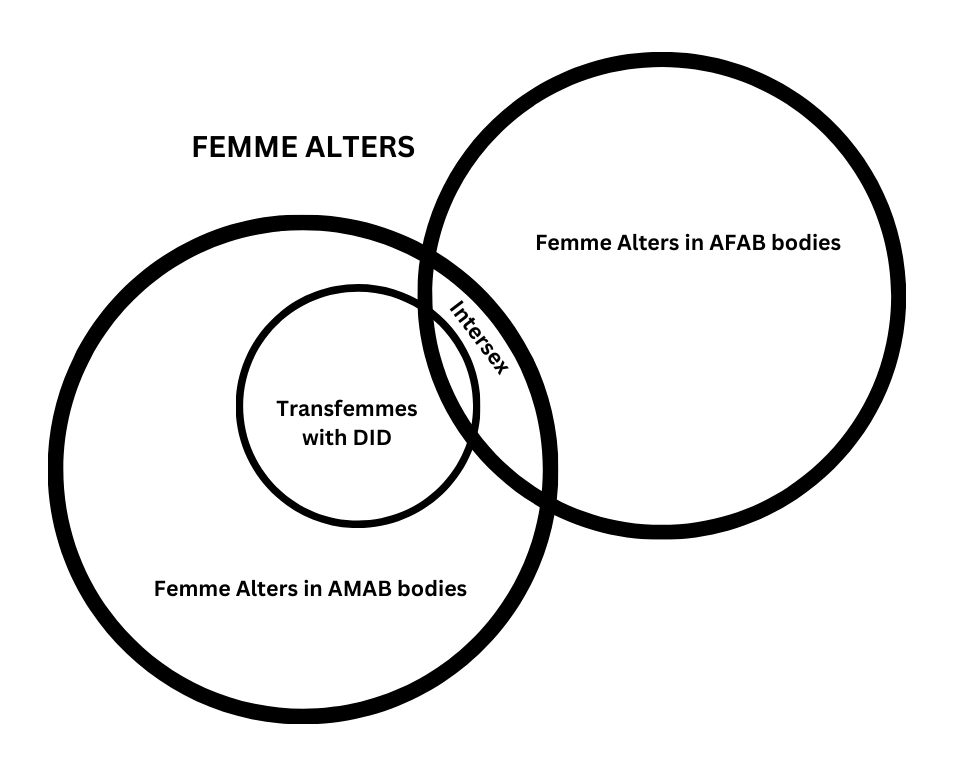

In this section, I’m going to be treating the intersection between plurality and transfemininity in two broad categories. Firstly, I’m going to discuss transfeminine people who happen to have Dissociative Identity Disorder. Secondly, I’m going to discuss the situation of femme-presenting alters who inhabit bodies that have been assigned male at birth. Ergo, first body-to-mind, then secondly mind-to-body. While there are a lot of similarities between transfemmes and femme-presenting alters in AMAB bodies, it’s important to recognize that many femme-presenting alters do not identify as trans. While a strict adherence to Julia Serano’s definition of “trans” would certainly include them as individuals who experience a dissonant subconscious sex, femme-presenting alters are not a gotcha tell-tale sign that the AMAB system as a whole is an egg or a trans woman in denial. There are men with DID who simply have femme-presenting alters while remaining satisfied as a collective with their assigned sex at birth.

One might be tempted to cite the fact that DID is more prevalent in women than men as “evidence” that men with femme alters are trans women in denial. This is bioessentialist bullshit, and it has way, way more to do with the fact that young girls are at a severely higher risk to experience childhood sexual abuse than young boys.

It is crucial to my argument that you understand that alters are people just as much as singlets are people – or, more accurately, that even if the system as a whole is only one “person,” no one alter has a stronger ontological claim to being that “person” than any other alter. Many systems live with the ongoing dissonance of having both a “collective” identity and a “personal” identity. What this means is that it’s possible for an alter to both be A) a trans woman with DID and B) a femme alter in an AMAB body. The two are not exclusive, often overlap, and each provide their own unique challenges. Basically it’s a Venn diagram. Let me visualize this for you:

So basically, all transfemmes with DID have femme alters in AMAB bodies, but not all femme alters in AMAB bodies identify or want to identify as transfemmes with DID. (It should be noted that you could make a near-identical graph for masc alters and the same would hold true).

There are so many commonalities between trans identity and dissociative identity. One of them is a vast statistical underrepresentation arising from a severe and systemic discrimination – both the trans and plural communities are hard to accurately survey because of the secrecy that has often been necessary for survival. We don’t have accurate demographic data, and thus it is neither useful nor important to speculate on their statistical correlations until better research can be performed.

From our first perspective – trans women with DID – it’s clear that much of the “comorbidity” can be attributed to how severely trans children are at risk of significant childhood trauma. Awareness of gender arises young; a common age people cite for when they “knew” they were trans is around four or five, and that awareness of trans identity comes with a childish innocence. How should the trans child know that her father might abuse her for wanting a dress? Even without the slightest bit of psychological knowledge, it should be pretty obvious how easy it is for a trans kid to develop a serious issue with dissociation – they want something gendered, their parents scold them, the desire doesn’t go away, so they keep it to themself. Hide it from themself. Hide it well – really well. Hide it until “they” aren’t the one who’s hiding it at all.

So being trans alone can be sufficient trauma to plant the seeds of a dissociative disorder. That’s a risk factor, but generally not considered an ACE (Adverse Childhood Experience, the metric for severe childhood trauma used by clinical professionals). What it risks are all of the other systemic violences faced by trans women. Sexual abuse and harrassment. Physical violence, both within and without the home. Verbal, emotional, and physical abuse. Physical neglect – and yes, I would argue that allowing your child to wither from dysphoria is a form of neglect. In severe cases, unhousing and homelessness at a young age. Conversion camp. Ritualistic abuse. Abandonment. So on and so forth. Any one of these experiences can cause Dissociative Identity Disorder – even something as simple as bullying can cause DID – and trans women are often subject to a lot of them.

It is extremely common in transfeminine systems for there to be a male alter who develops in order to present the facade of a functional boyhood and keep the collective in denial. What this means is that it is very, very common in transfeminine systems for a power dynamic to form in which femme-presenting alters face violence from male alters in order to preserve the state of denial and keep the egg sealed. But this physical, mental, and sexual omnipresence of violence in the life of the femme-presenting alter goes beyond just trans women – it is a shared experience in the lives of many femme-presenting alters in AMAB bodies, especially when the system formed as a response to sexual abuse.

Whether that violence comes at the hands of a male alter or a masc-presenting transfemme in denial is completely irrelevant – internalized patriarchy is the operative principle of this form of abuse either way.

Nobody talks about intra-system sexual violence. Or if they do, it’s always framed as “oh well they’re just reliving past experiences, if they just heal from that trauma, they won’t have to imagine sexual abuse anymore.” This strips away any semblance of agency from alters who experience intra-system sexual abuse, and completely effaces the possibility of their personhood. In this sense, sexual violence is one of the fundamental forces which undermines the potential personhood of an alter. The abusing alter is not committing sexual trespass – he is a personality, he is a trauma response, he’s just programmed to be that way. And the femme-presenting alter is programmed to lay back and take it.

It’s a misogynistic construction, pure and simple. And the presence of intra-system sexual violence is even more normalized in AMAB systems, where excusing such violences as a “coping mechanism” is almost standard therapeutic practice.

Boys being boys – literally.

Don’t think that society doesn’t recognize this. There is very much an implicit understanding of the shocking and gruesome frequency of intra-system sexual violence in the public imagination of Dissociative Identity Disorder. Does that mean that society has a feminist praxis regarding the autonomy, personhood, and therapeutic protection of femme-presenting alters?

No. Nope. Not at all.

Basically it just means that all plural bodies get treated like (transfeminized) serial killer rapists.

The Transmisogyny of Popular Pluralphobia

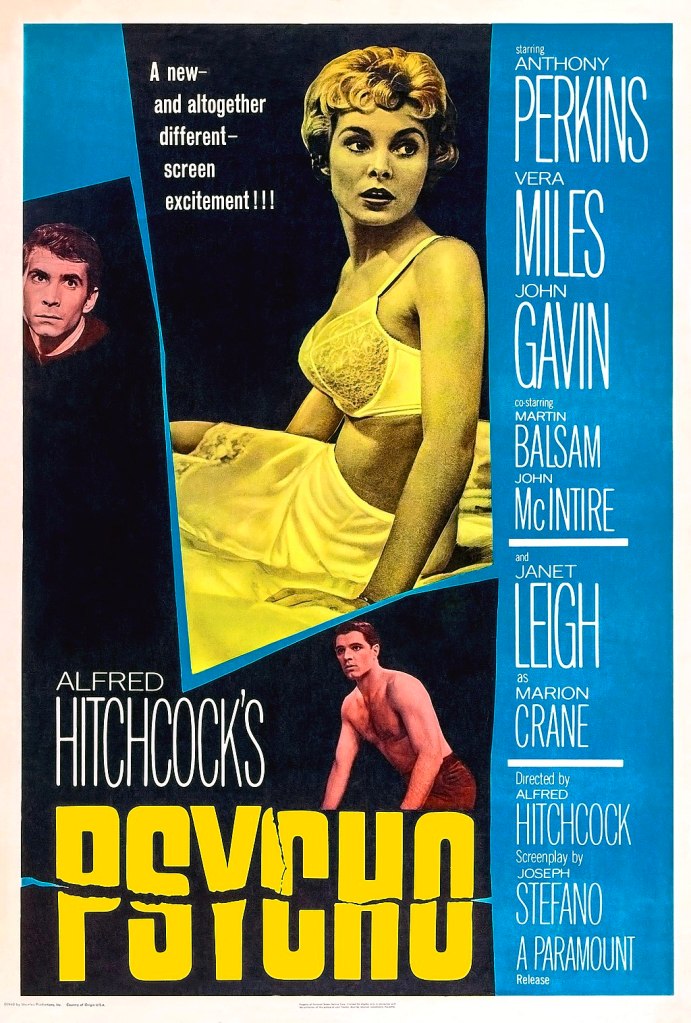

Oh, Alfred Hitchcock. We were going to have to talk about you eventually.

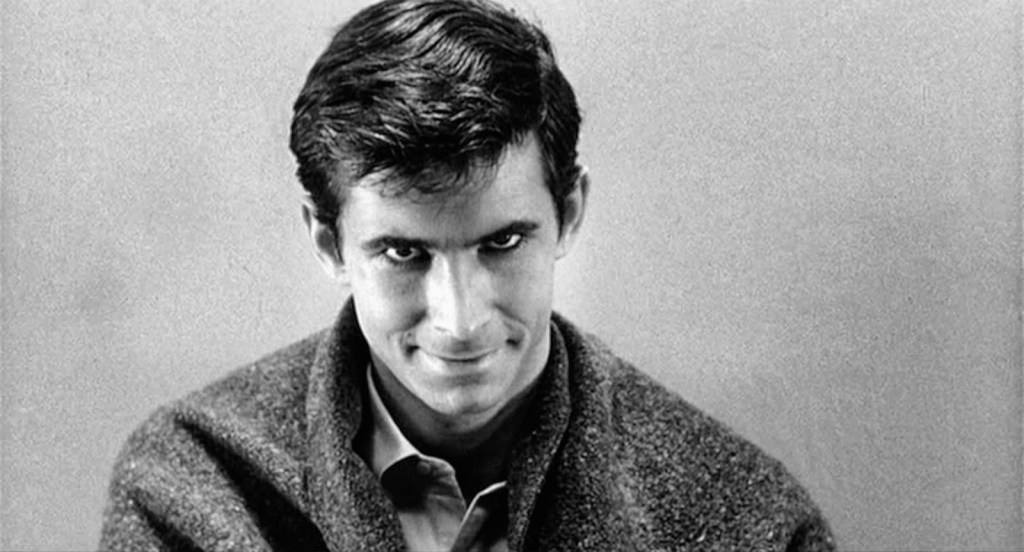

Meet Norman Bates.

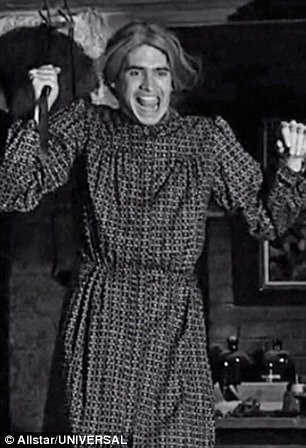

Norman Bates is an evil psychopathic murderer. He also clearly has some form of either schizoaffective or dissociative disorder which has caused him to converse with his “mother,” who also happens to be a serial killer. Norman Bates is a sexual predator who “becomes” the alternate personality of his mother (who he murdered) whenever he is attracted to a woman, who then proceeds to kill said woman out of “jealousy” because his “mother” wants Norman all to herself. Implicit here is the Freudian Oedipal Complex – Norman wants to fuck his mother, he killed his mother, he is his mother. All of the nastiness. Effective horror, right? Norman Bates isn’t just an icon – he is the archetypal psycho, the main character in the film that bears that name.

The poster for Hitchcock’s classic 1960 film Psycho advertises it from the cover – an innocent white lady stripped down to her underclothes with the ominous figure of a male predator lurking in the shadows. Lots of trans readings have been made of this movie, but almost none of them have been plural-sensitive. What I mean is that while Norman’s “mother” is often written as a reflection of Norman’s predatory desire for young woman in the external world, there is a corollary reading wherein Norman’s predatory serial killer behaviors against young woman are a reflection of his inner tendencies toward the rape and murder of the imagined figure of his mother. The two are symbiotic, and while transfeminine activists and writers have been largely successful at unthinking the idea that transitioning to be a woman somehow represents a predatory sentiment toward other women, there has been a broad failure to grapple with the fact that an external mythos of the plural person as a sexual predator completely overwrites the actual reality of post-traumatic sexual violence faced by many femme-presenting alters. This is A) a violence that affects nobody outside of the system, B) is almost always invisible, and C) often emerges due to molestation and childhood sexual assault against young boys, which is a notorious source of shame, secrecy, and violent suppression. It’s victim-blaming pure and simple on multiple levels – both victim-blaming against young male victims of sexual violence, and victim-blaming against the femme-presenting alters who have the misfortune of growing up within those crucibles of violence and repression.

But no, of course Norman Bates only kills his female victims while wearing a dress.

What this produces is a certain collapse of the feminine alter into her male sexual abuser – another clear symptom of society’s inability to conceptualize alterhood – out of which emerges a particularly unholy abomination of the popular conscience: the “killer alter” trope, or the omnipresent image of the plural serial killer.

This is – extremely unfortunately – a trope that gained traction due to a real-life manifestation. In 1977, the serial killer Billy Milligan, better known as the The Campus Rapist, went on extremely public trial for his horrific crimes. Milligan had DID and attributed many of his crimes to his alters, and in doing so, would leave a stain on the entire plural community that still lingers to this day.

One of Milligan’s alters was named Adalana. Adalana was a femme-presenting lesbian in an AMAB body. She was a caretaker alter who took care of the system.

She was also allegedly responsible for all of Milligan’s rapes.

So the woman – more importantly, the lesbian in a male body – is the rapist, and the man is merely the accessory to her crimes, the murderer silencing the victims in her wake. We cannot overstate how prolific this image of plurality became. This is hardly the only reason why Milligan’s story is so destructive to the plural community, though. Billy Milligan’s other claim to notoriety was the fact that because of his DID, he escaped a death sentence and was institutionalized on an insanity defense instead. In essence, Milligan was able to use his DID as a way to avoid accountability for his crimes, which has created the pervasive lie that not only are people with DID dangerous serial murderers and rapists, but also that their DID is a convenient tool to literally get away with murder. This is manifestly false, and we’ll discuss the concept of “system accountability” in the final section of this essay and why it’s so important for authors to portray in plural-informed fiction, but for now I want to keep tugging on this thread of the femme alter in the mythos of the plural serial killer.

Billy Milligan has been immortalized in film and true crime documentaries many times now. One of the more notorious recent depictions of DID was based off of Milligan – M. Night Shaymalan’s 2016 movie Split, where the “caretaker” alter Patricia runs a tyrannical cult in her AMAB body that oppresses her innocent male alters and harnesses the power of “The Beast” to kidnap, murder, and eat teenage girls.

Let’s not cut teeth – Billy Milligan was one of the worst human beings to ever walk the face of this Earth, and anyone who says otherwise or tries to defend his alters needs a hard reality check. He was in no way, however, representative in any way of Dissociative Identity Disorder as a condition, and anyone who tries to claim so is a bigot. What Psycho, Milligan, and Split all obscure is the way that intra-system violence affects alters – how the actual victims are disproportionately not other humans in the physical world, but marginalized alters within closed systems of power that have little to no means of seeking external aid or support. Depictions like this are to the detriment of everyone in a dissociative system – by blaming the femme-presenting alter for the state of sexual violence in headspace, popular media both silences the victim and stigmatizes the perpetrator, driving the system further into denial and rendering ever-more-distant the possibility of healing, restorative justice, and community care.

The clearest illustration of the fact that the general populace has a underlying intuition of intra-system violence comes from the 2003 horror film Identity. This film gets rightfully critiqued for perpetuating the “killer alter” trope, but to this day, it is probably the only piece of popular media to ever take a hard look at intra-system violence, and in a plural-informed audience, becomes an indispensable metric for unthinking system power dynamics. So let’s talk about it.

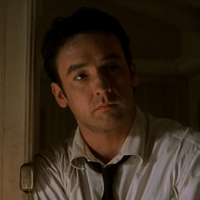

Paris Nevada is a sex worker who’s pulling a reverse Maria Griffiths and driving to Florida to start an orange orchard, and she is one of the most badass trans characters in cinema who gets absolutely no recognition whatsoever. Ed Dakota is a retired ex-cop who finds himself in the midst of a string of inexplicable murders at a motel (which is definitely not just the Bates motel reskinned with Aughties graphics), and the two of them attempt to get to the bottom of the mystery. Paris and Ed also both have the grave misfortune of being alters in the body of serial killer Malcolm Rivers, who is currently sitting on death row getting tested for insanity.

What really makes Identity stand out from movies like Psycho and Split is that is has a staunch commitment to depicting the interiority of life with DID, albeit through the chokingly pluralphobic lens of the mind of a serial killer. Even though the watcher knows from early on that Malcolm has DID, the alters don’t know that, and are stuck in a pantomime of a murder mystery, trying to understand why their world is coming unraveled at the seams. Paris and Ed don’t understand that they’re alters – they’re people, people who are trapped in a horrible violent situation, and they need to find a way out. In plural circles, Identity is rather notorious for perpetuating the idea that one alter can “kill” another – which is complete bogus, for the record – but a far more meaningful way to read this is not as a literal murder but rather as a metaphor for the inescapable dread of intra-system (sexual) violence which so many alters face, especially an alter like Paris Nevada, a sexual protector in an AMAB body that has other alters who have committed unspeakable acts of violence in the real world before.

The point isn’t that people with DID are serial killers who murder even their own alters in their sick, twisted mind. The point is that when the individuals in headspace have spent the entire movie desperately searching for a way out of their situation, the entire emotional crux of the film comes in like a fucking wrecking ball.

They’re alters.

They’ll never be able to escape their body, because they literally inhabit it. They’ll never be able to escape the serial killer – the thread of (sexual) violence – in their own mind.

They’re trapped.

Identity‘s twist isn’t even a surprise for the viewers, but it works – not because it’s shocking that Paris and Ed are both alters of this serial killer, but because the viewer suddenly has to grapple with the sheer dread of realizing that this beautiful plucky badass of a young woman is trapped inside the mind of a vicious male serial killer, forever, and that she is completely at his mercy and there is nothing anyone can do about it. You cannot save her. She cannot save herself. The only person who can offer her mercy is Malcolm, and well- It’s pretty obvious there’s no chance of that. As a film overall, the conceptuality of Identity is voyeuristic and gross. But as a femme alter, I can’t help but find Paris to be deeply relatable. Far more so than recent progressive portrayals of DID in film like Marvel’s Moon Knight (2022), I see myself in her, her struggle, her terror, the inevitability of her fate.

“It could be Multiple Personality Disorder”

I want to take a moment to shout out what is, as far as I can tell, the only other extended scholarly account by a trans plural person that’s ever been written on this topic. Small Cedar Forest’s 2014 article “On Transgender and Plural Experience” was enormously helpful for me while I was figuring out my plurality, and it provided a really crucial groundwork for the plural-informed transfeminism I’ve laid out in this essay. One of the major focuses of Cedar’s article was tracing the similarities between the clinical treatments of DID and gender dysphoria. Cedar wrote:

As with many trans people, those that do not have the “right” way of experiencing their plural identities are treated as suspect. While our own experiences with plurality have not always been positive, we have also found switching to be very positive and healthy for us. People should trust, at the very least, what others report as their subjective experience. Plurality should be defined by the subjective experience of having multiple selves, rather than requiring a specific narrative and formal diagnosis under a pathologizing framework. […] Having your experiences invalidated and pathologized, and being told that your experiences aren’t real (or are less legitimate) if they don’t follow a prescribed narrative, comes with significant personal consequences. All of this gets internalized and can lead us to seeking external validation rather than trusting in our own experiences. This was very much the case for us with respect to being both trans and plural. As we came to understand ourselves as trans, we went through an intense period of obsessively comparing our own experiences of being trans against those of other trans folks, and against mainstream understandings of trans experience. When things deviated from these narratives, we became very worried that our experiences were not legitimate, and that we were making things up to get attention or distract ourselves from other difficult aspects of our life. As we came to understand ourselves as plural, we had a very similar experience with obsessively comparing our narrative against that of others. […] This left us feeling really lost; knowing that we were experiencing aspects of plural selves that we couldn’t deny, but not feeling that we were “really plural”. I’ve heard attitudes towards non-binary gender folks as being as if you can pick the “male box”, “female box”, or “crazy box”. I felt like all I had left with my experiences of plurality were the “crazy box”, not being really plural, but definitely being different from a singlet. However, the more I chatted with plural folks, the more I recognized an incredible diversity of experience and that our experiences were actually more typical than not. It has taken us a long time to trust our own experiences as legitimate in themselves, and not need a great deal of external validation to feel okay.13

Cedar does a great job at observing the links between the clinical literature on DID and dysphoria, but the rabbit hole goes deeper than what they observed. From the early sexological days, male doctors who took an interest in the transsexual phenomenon were aware of the possibility of co-ed dissociative systems with both male and female alters. It would thus become an important part of the screening process for trans people, especially trans women seeking bottom surgery, to ensure that they did not have Multiple Personality Disorder. If a person did have MPD, then if they had even a single male alter, then it was assumed that they “weren’t really” a woman, and their gender affirming care was summarily denied.

This was in no small part due to the Harry Benjamin Standards of Care, the organizing document which provided the rules for all gender affirming healthcare in the later years of the 20th Century, which in turn cited the DSM-III, the then-current version of the core text of clinical psychotherapy which provides the official definition for every mental health condition. The DSM-III had a clinical diagnosis of “transsexualism,” which had the following conditions:

A. Sense of discomfort and inappropriateness about one’s anatomic sex.

B. Wish to be rid of one’s own genitals and to live as a member of the other sex.

C. The disturbance has been continuous (not limited to periods of stress) for at least two years,

D. Absence of physical intersex or genetic abnormality.

E. Not due to another mental disorder, such as schizophrenia.14

Obviously Clause E of this definition would have automatically precluded anyone showing visible signs of plurality from receiving SRS and other gender-affirming care. But there’s a double-embargo against the existence of plural trans folks here, and that’s the requirement of a continuous dysphoria. A male alter fronts twenty-two months into your two-year stretch and decides to be a little shit on main? You can kiss your hormones goodbye.

Plural trans folks in the 20th Century were uniquely positioned to not be able to receive healthcare; if you were openly plural and trans, you were far more likely to get institutionalized than you were to receive hormones. Even as awareness of trans bodies and identities steadily grew in the late 80s and 90s, MPD remained a stubborn sticking point for many gatekeepers of trans healthcare. I find the 1988 case study “A case of concurrent multiple personality disorder and transsexualism” by P. G. Schwartz to be particularly illustrative in this regard. This is a long quote, but I think it’s important to give a thorough picture of the way that MPD and transsexuality orbited each other in the psychological establishment:

It is difficult to accord primacy to either the MPD or the transsexual diagnosis in this case. The history indicates that the development of the two conditions was intertwined from the beginning, and appears to originate in the insistence by mother that her son be treated as a girl, and in the pervasive sexual abuse that has permeated the patient’s life from childhood until the present. The patient appears to have developed a gender identity disorder of childhood that progressed into a fixed transsexual adaptation, and to have developed a childhood form of MPD that became a rather classic and florid adult MPD condition. It would appear that mother’s efforts to give the patient a female name and dress him as a girl prevented the patient’s separating from the mother at an age-appropriate time, with the result that his preferred role model did not undergo the usual male transitional patterns of changing from mother to father (Stoller, 1968, 1985). Sexual reassignment surgery is irreversible. The choice to undertake it or not should be made in an atmosphere of free choice and informed consent, with full awareness of the possible consequences. It is doubtful that most MPD patients can make such a decision in an unencumbered manner. Furthermore, because the alters of an MPD patient may seize control and succeed in representing themselves in a transsexual pattern, and seek sexual reassignment surgery to solidity their claim to be truly and irrevocably in power, it is crucial to rule out MPD in potential candidates for this rather drastic form of intervention. Based upon his experience consulting in situations that involve transsexuals, Kluft (personal communication, September, 1986) concludes that the definitive treatment of the MPD should precede the serious consideration of sexual reassignment surgery. In this situation, it is fortunate that the male alters in this patient concurred with the decision to be female. One possibility that this suggests is that both a true transsexual and a true MPD condition coexisted, and that the same patient would have made the same choice even if there were no question of MPD. However, it remains within the realm of possibility that this preference is the patient’s least narcissistically damaging response to an unwelcome and overwhelming fait accompli. In conclusion, it is evident that a thorough evaluation is essential prior to a patient’s being accepted for sexual reassign- ment surgery. This evaluation should be particularly sensitive to the possibility of concurrent MPD, or to MPD misdiagnosed as transsexualism. Working with dissociative defenses and the consequences of sexual abuse issues must not be overlooked in the required treatment preparatory to undertaking the surgical reassignment.15

I would posit that this historical attitude within the field of psychology (specifically psychoanalysis) elucidates both why so few trans theorists have taken the time to sit down and consider dissociation and femme alters, and why so many femme-presenting alters in AMAB systems are reluctant to claim the “trans” label as a self-descriptor. For the former, disavowing plurality was a matter not just of political convenience but of survival – it didn’t matter how often you blacked out for a few hours, if you let your doctor or therapist know you’d be off hormones faster than you could say “Susan,” and for some folks that was a matter of life and death. The latter group feels reverberations of the DSM-III and the Standards of Care too – definitionally, if you were an alter in an MPD system, you were psychologically incapable of also being a transsexual, and trans women on the internet would be the first people to tell you so. The diagnoses may have changed over the decades, but those sorts of social intuitions tend to linger long after their truth has passed.

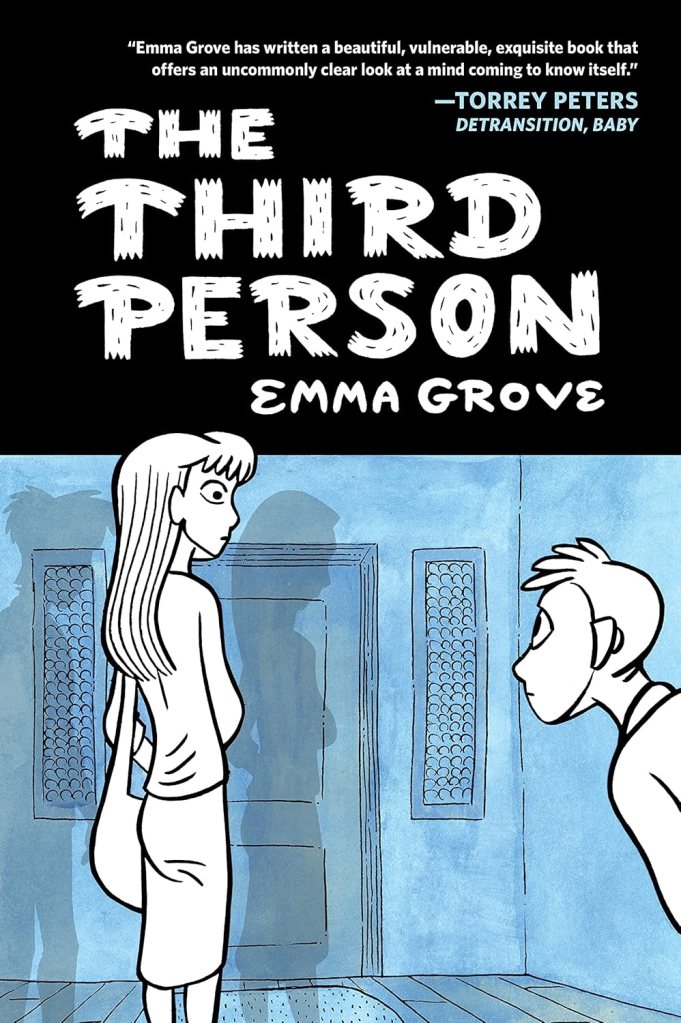

It’s at this point in the article that we finally get to shift gears and talk about depictions of plural identity in transfeminine literature! There are four books I want to talk to you about today, but I want to save the three novels for last. First though, we need to talk about one of the best trans memoirs, Emma Grove’s Lambda award-winning The Third Person, a graphic novel from 2022.

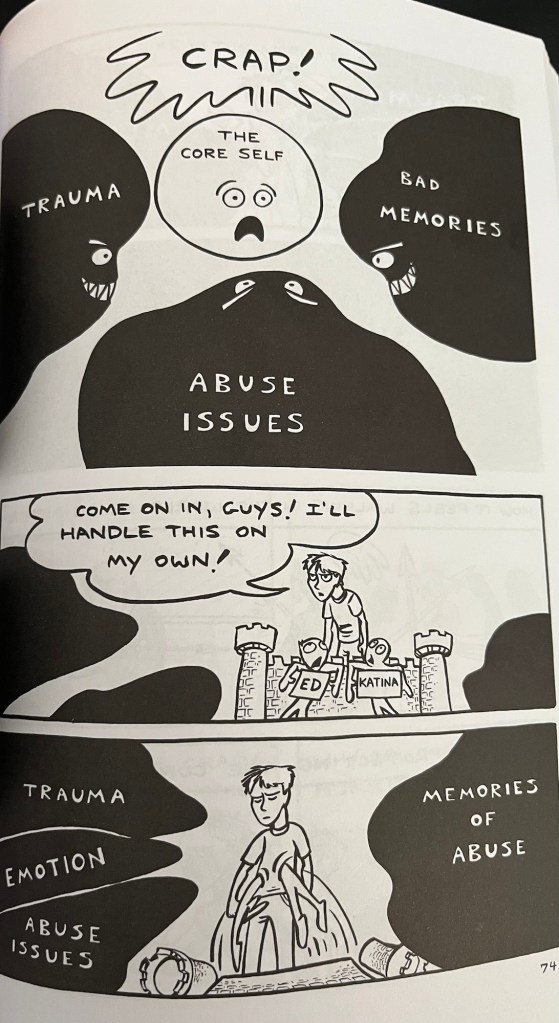

One of the reasons this book is excellent is that it offers a counterpoint to the narrative of plurality I’ve offered you above, and perfectly illustrates the fact that no two systems are alike, and no two healing journeys will run the same course. Emma’s therapy involved a final integration of all her alters, and The Third Person explores in depth what that process looks like, and what a powerful difference it can make in somebody’s life. Emma’s system had three alters – mine has twelve, some systems have dozens. One of the most important takeaways from this article should be that there is no correct way to be trans and plural. There are no litmus tests, no gatekeepers, no rules, no boundaries. Integration, functional multiplicity, something else entirely – at the end of the day, all that matters is your healing, your system, and how you experience your own gender, either collective or personal.

The vast majority of The Third Person follows Emma’s experience with her terrible gender therapist Toby, who is antagonistic, brutally skeptical, and ever so counter-productive to her healing journey. Toby yells, provokes switches, casts constant aspersions on her attempts to self-actualize, and, of course, casts Emma’s identity as a trans woman into doubt – a relationship which only begins in earnest when the therapist “discovers” her male alter Ed for the first time. The year in 2004. The DSM-IV may have been the ruling law of psychology for a decade, and Gender Identity Disorder may have replaced the old dogma of “transsexualism,” but the stains of doubt and ableism still linger upon the diagnosis. Emma is trying to receive gender-affirming healthcare through therapy, but her inability to recall any details from her childhood led her to a quick wall with her first therapist. Downtrodden, Ed tries again, but he’s doubtful that he’ll have any more luck the second time.

Emma’s system has a flawless solution to this problem:

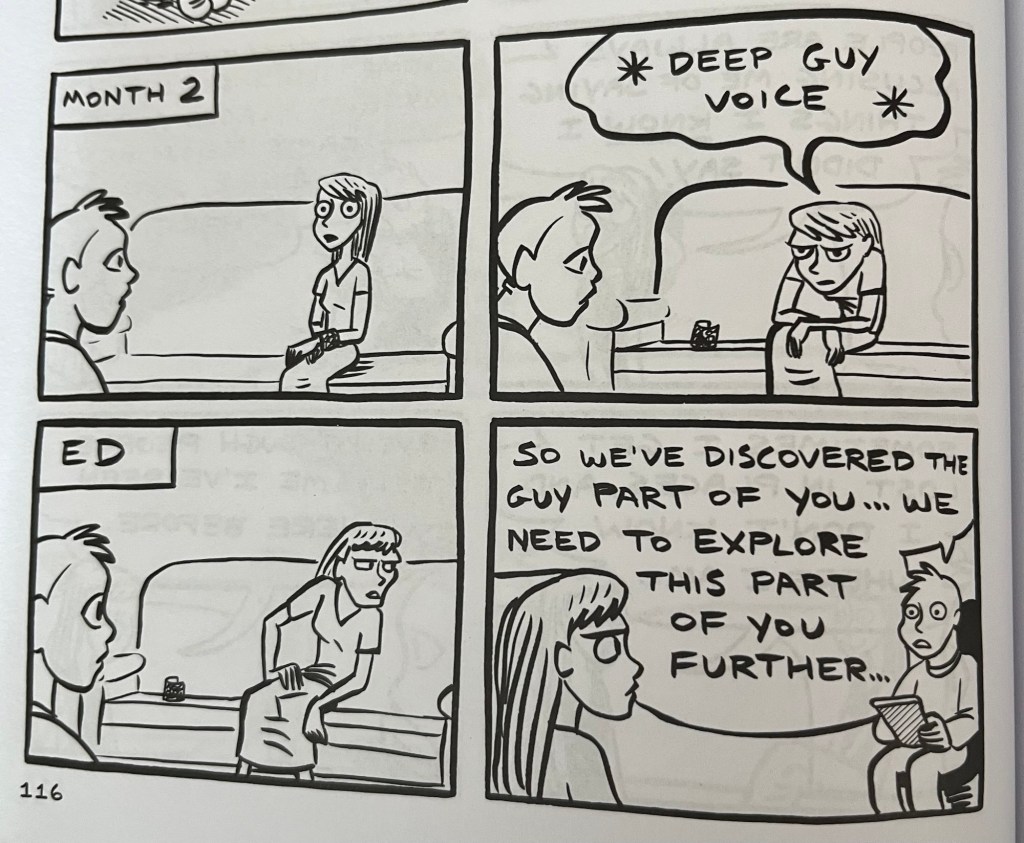

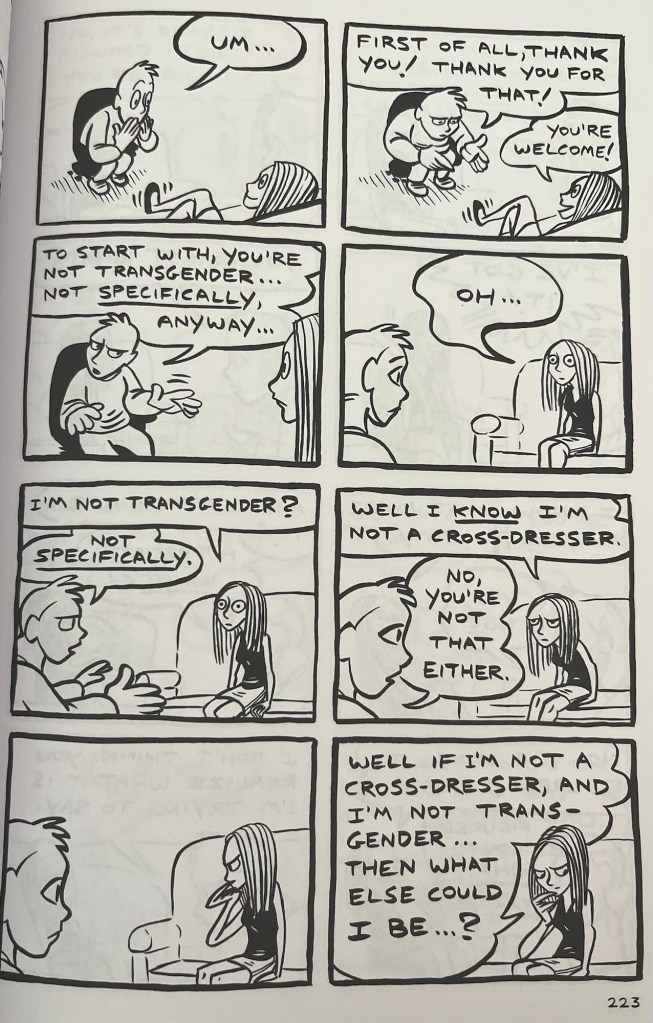

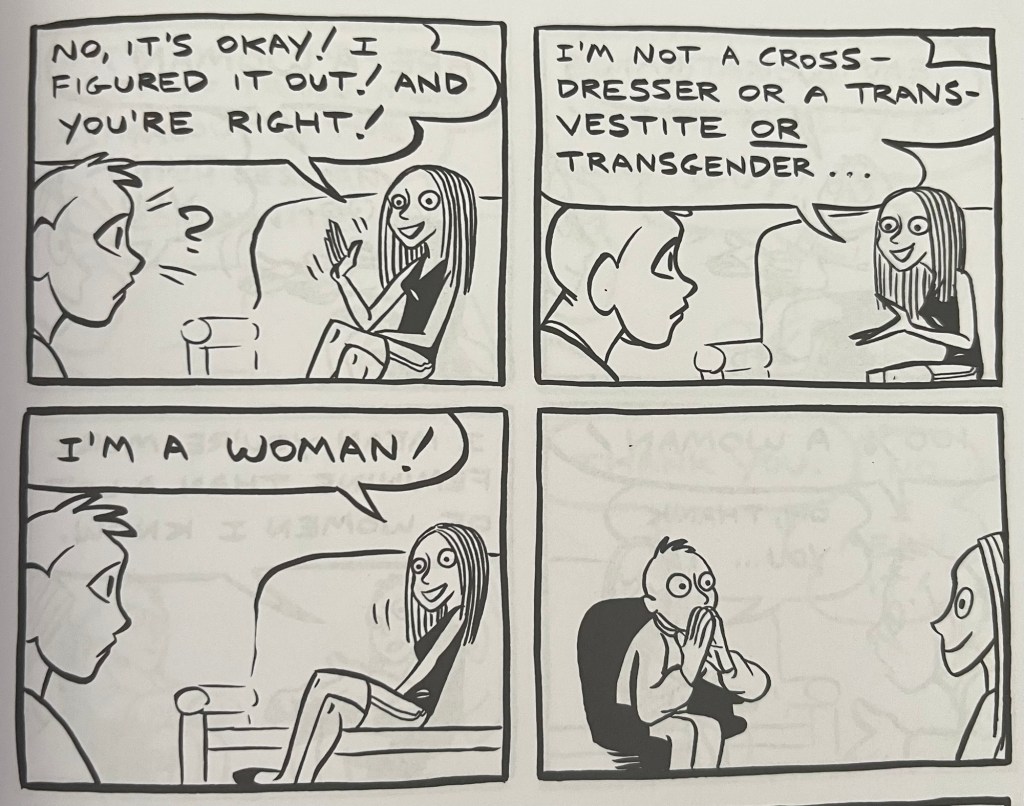

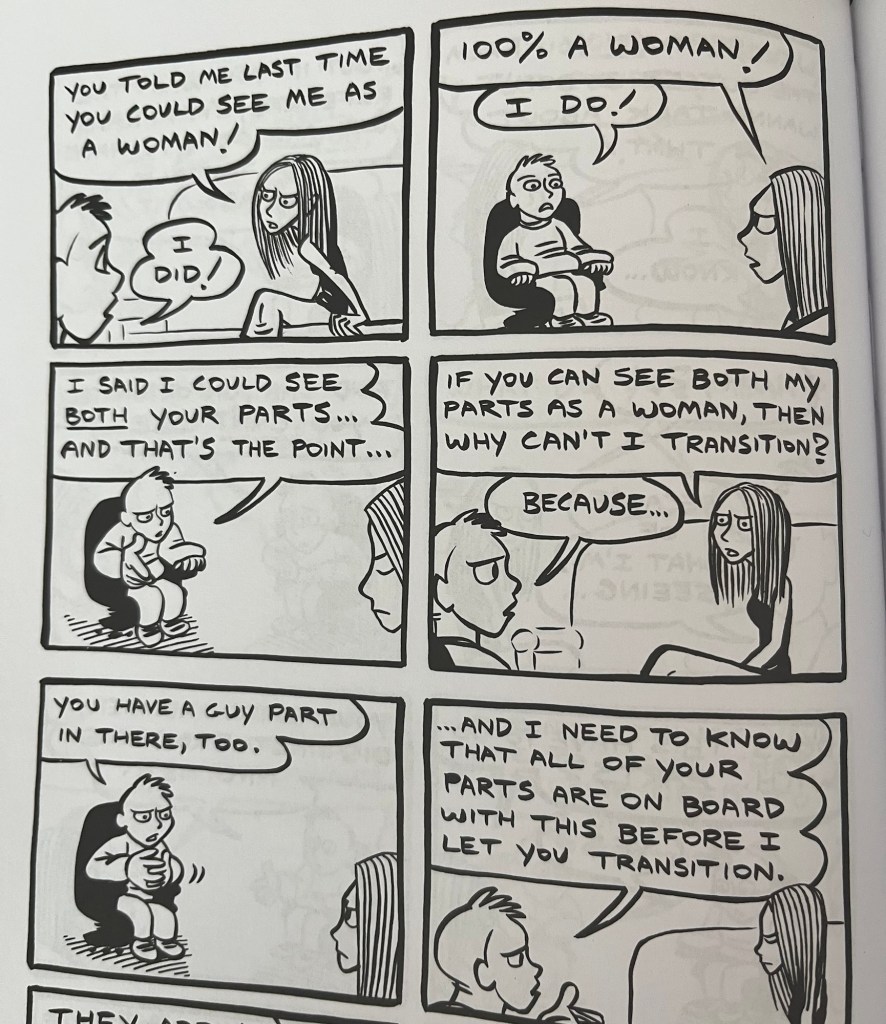

Katina sees Toby alone for two months, but it’s all glossed over – something isn’t right. Toby has been waiting for a “Gotcha!” moment, and, well, he gets it:

Here we get a very, very clear picture of how the rupture from transness happens for femme-presenting alters in AMAB bodies, even for alters who are part of a trans system. It does not always occur because of a lack of self-identification – just as often (sometimes implicitly so), it is a direct response to systemic forces of transmisogyny and disbelief on the part of the various gatekeepers who control trans plural life which leads to femme alters disassociating (and dissociating) themselves from overt declarations of trans identity, only reinforcing an overarching society belief that transfemininity is a fundamentally undesirable or dangerous condition. This odious sense of transfemininity as a stain or taboo lends itself to the production of a social contagion-esque derationalization of transfeminine alters – if even one alter makes the body look trans, the AMAB system rationalizes, then the whole system could appear like a tranny fag by association.

And then, because plural trans women are better than just about anyone else on the planet at rationalizing away all of their problems (the problem in this case being that Toby takes the lone male alter as a sign that they can’t be a trans woman):

The next session, Toby lays this out for her in no uncertain terms:

The implicit ungendering of the fact that Emma’s system A) isn’t trans, B) isn’t a woman, and C) isn’t a man who can say otherwise, even though D) the only reason that A and B have been held is a premising of her ontological manhood, is transmisogyny at its absolute worst. The plural system isn’t any gender. They collapse into themselves. The psychic man and the psychic woman cannot coexist – their only recourse for their sheer implicit impossibility (and the agony presumed) is to kill someone else, or rape each other. Either way, inevitably, they self-destruct.

Hence why The Third Person is a harrowing 900-page odyssey instead of a 20-page feel good comic about a plural transfemme finding herself.

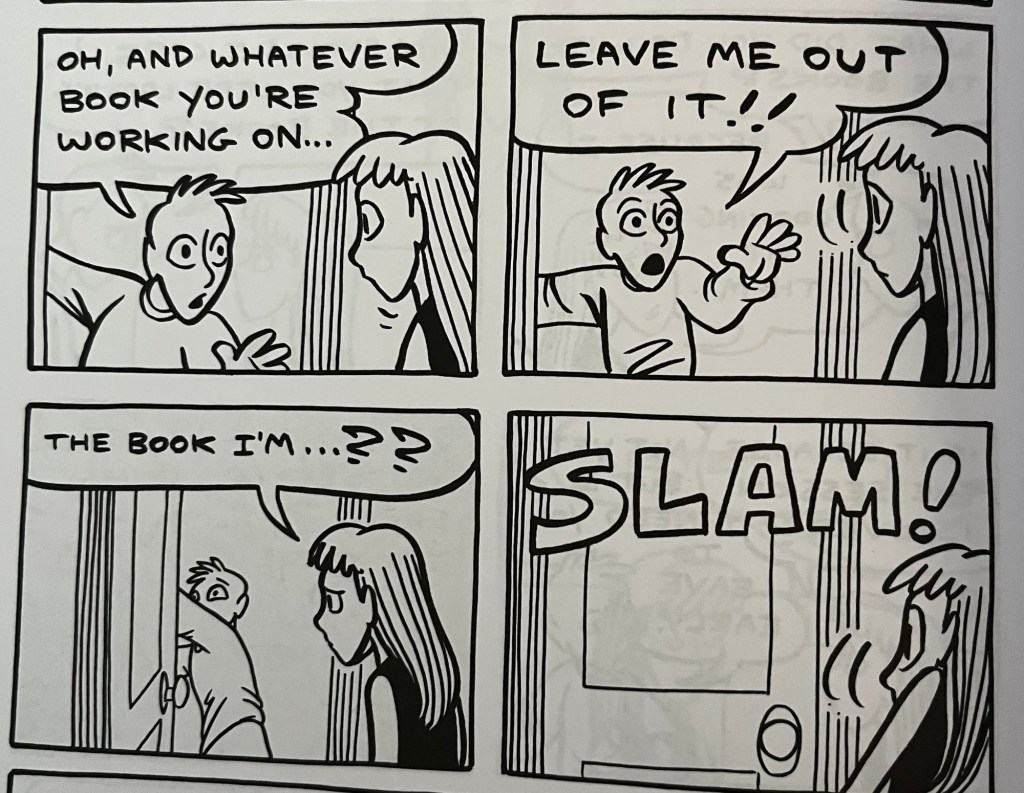

There’s a lot more to be said about Toby’s role in The Third Person, but, well…

The few sections of the book focus on Emma’s integration journey after getting away from Toby’s poor therapeutic practices, and I’ll be the first to confess that it absolutely made me sob when I read it for the first time. It’s done so beautifully well and I won’t spoil it by showing the panels, cause I think that all of you should go read this book, but after almost nine hundred pages of black-and-white illustrations, the final moment of catharsis explodes into vivid color, and it’s a downright spiritual experience.

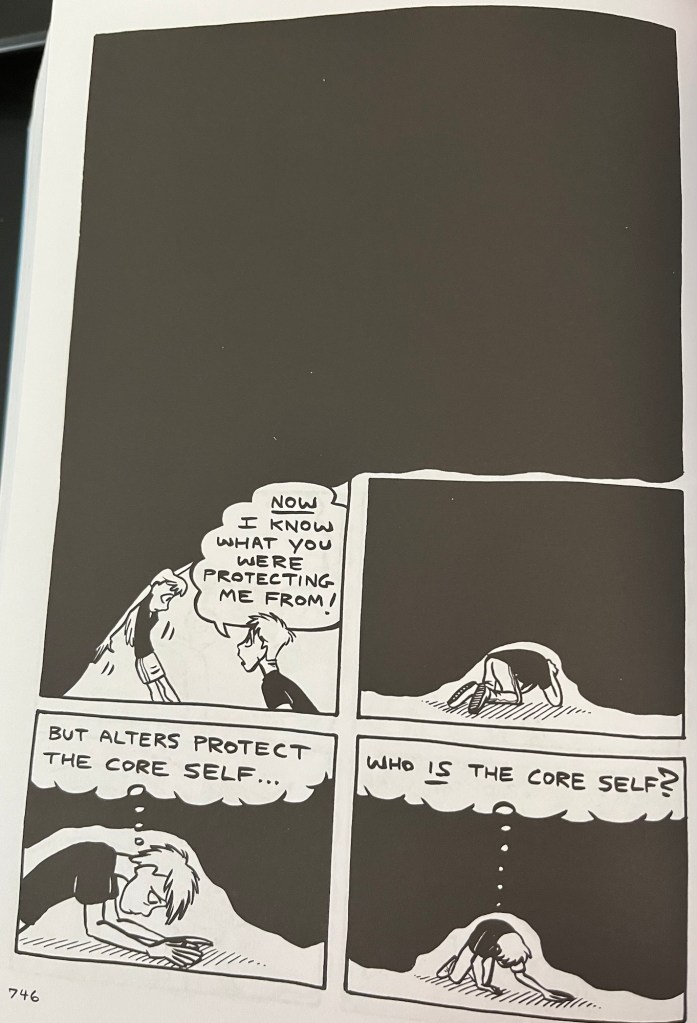

No, instead, the final image I want to show you from The Third Person illustrates how this memoir tells what we might call a “Classic DID” story, i.e. one that, while progressive in its interpretations, still hews to a conventional Post-20th Century wisdom about the prognosis, treatment, and desirable outcomes for patients suffering from Dissociative Identity Disorder. It starts with a life full of confusion and amnesia, continues with a grueling journey in therapy, and concludes with a happy, healthy, newly integrated protagonist who’s finally ready to face the rest of her life like any other singlet would. And we love that for Emma! For a lot of people living with dissociative disorders, integration is the correct goal for their needs and life desires. But before we talk about the diversities of other depictions of plurality in transfeminine media, I want to give Emma the final word about integration, core alters, and whatnot, cause Lord knows she’s a way better resource for the plural transfemme than any of the psychologists I cited in the first half of the essay:

Who indeed?

CORE_FAILURE

“I want to get back to something you said, Scratch,” says Winc around a mouthful of waffles. “Something you were saying about sensory overload.”

Scratch, who I swear looks one minute like everyone’s mother, and the next like some guy in drag, and the very next minute, well, strong and proud, gets all quiet and nods, so Winc keeps talking.“It ties in with something I was saying, about the courage you’ve given me – online. See, I did want to be a woman, Scratch. I really, really thought that was the answer for me. But when I finally did it, it felt like I was still acting.”

It was weird hearing all this come from a doode with a mustache.

“All my life, I played at being a boy, and when I finally became a woman – and that’s what I did, Scratch, I became a woman – I found I was playing at that too. It was too tight. Too many rules on both sides of that gender fence, and I just don’t get along well with rules.”

Scratch looked a little more like what I think ze really looks like then. “So online,” ze says, “you got to escape?” Winc nodded, and then Winc took a deep breath.

“I fell in love with you a lot of ways, Scratch. I loved being boy to your riot grrl. I loved being nasty gay man to your nasty gay man. I even loved when you were a vampire and I was… um… food. I fell so deep and hard when we were Frankie and Johnny. And then Razorfun and Gyrl…”

I felt embarrassed but thought that what ze was saying would maybe save this whole thing.

Hir voice trailed off, and Scratch’s eyes got a little wet and ze just nodded some more. Winc went on. “What I’m realizing now,” ze said, “is that I was falling with a safety net.”

Winc was getting sadder and sadder, but ze kept talking. “I was finding a way to be all the different me’s I could be, with you. But it wasn’t with all of you, not really. A lot of it was in my head. It wasn’t really you. It was the you I wanted you to be.”

Ze just stopped and looked down, and took another bite of hir waffle, but I don’t think ze was hungry. Scratch took up the slack.

“So you were becoming who I wanted you to be?”

“Sort of.”

Scratch looked disgusted with hirself.

“It was always someone I wanted to be too,” Winc went on. “I loved that no matter who we became, you were right there with me. We both had the safety net. I… I didn’t have to worry about looking like a freak to other folks. You didn’t know you’d be with a freak.”

Right then, the waitress comes back and asks Winc if “the table” wants more coffee. So Winc says, in this girly voice ze usually uses, “Thanks, hon, yes please,” and the waitress just stares at hir, pours the coffee quick and gets outta there.

“You’re a freak?” Scratch said when she was gone. “You think you’re the only one? Don’t you know I’m one, too? Why do you think there’s so many of us online. Not just queers either, but lots of people are freaks out there.”

Ze looked around the diner. “I mean, out here.”

Winc looked kind of surprised, but didn’t say anything. Ze had a kind of “tell me more” look in hir eyes.

“You were trying to make me complete some kind of fantasy, right?” Scratch added. “Something to make you look more normal?”

Winc nodded, tears spilling out of hir right onto the waffle.

“You sort of used me, Winc,” says Scratch, real quiet. Winc was crying now; ze just nodded and said ze was sorry.23

Nearly Roadkill by Kate Bornstein and Caitlin Sullivan occupies an odd position in the broader transliterary sphere. Published in 1996, the novel is long out of print. Most transfemmes have probably at least tangentially heard of Bornstein’s work, yet basically nobody knows that they wrote one of the first real tradpub novels to get into the nitty-gritty of an actually progressive look at gender identity and trans issues. Similarly, basically none of the other scholars of trans literature have been able to make heads or tails of it, and tend to get relegated to the requisite “Oh, and here’s all the other books from before Topside that I want to mention but don’t know how to discuss” paragraph. As a work of fiction, Nearly Roadkill manages to be simultaneously dated to the point of unreadability and still ahead of even our present moment almost thirty years later. I’m not going to attempt to explain how this book works, or why there’s so many awful cyber sex scenes, or how you should read or even acquire it. It’s a proper Experience, and I don’t really think I’ll be able to do it justice. Rather, what I want to talk about is Bornstein’s radical depiction of plurality and how astonishing it is for a book written in 1996.

Textually, Winc is not plural, or at least it’s insinuated that ze aren’t, not in the formal sense of Multiple Personality Disorder. That being said, I would argue that Winc’s relationship with Scratch gives us a really interesting look at the other side of the transmisogyny/pluralphobia dynamic. In Emma’s case, the discovery of plurality delegitimizes Emma’s desire to receive gender-affirming healthcare. In Winc’s case, however, it’s the discovery of transfemininity that delegitimizes both Winc and Scratch’s belief that Winc’s polymorphism and identity-play could ever have been an act of true freedom or radical unsettlement in the first place, suddenly turning Winc’s identity-play from an act of rebellion to a statement upon hir character (or lack thereof).

Let’s rewind to a bit before the long quote above. Winc and Scratch are notorious cybercriminals, the terrors of the early internet. They descend upon random chatrooms and have extremely long, elaborate, and public cybersex roleplay scenes. Most of the time they don’t know who the other person is until halfway through – they’re essentially digital soulmates. Doesn’t matter what name they’re using or what role they’re playing, they’re gonna end up fucking each other in public (and yes, the premise is exactly as ridiculous as it sounds).

What keeps Nearly Roadkill from being a bizarre relic of 90s erotica comes in the middle of the book, when Winc and Scratch, now on the run from the law, meet each other in person for the first time. Suddenly they are not disembodied spirits, ever shifting in the void; suddenly they are here, present, physical; suddenly, their bodies matter. And, well…

“Okay, okay,” says Scratch. “Here’s what I am.”24

Once again, the ontological imperative is announced by the arrival of the flesh. Here are two characters who have been everyone and anyone for the last two hundred pages – for all we know, they don’t even have bodies! When I read Nearly Roadkill for the first time, I had absolutely no mental image of either Scratch or Winc until this scene. Each of their incarnations seemed a person(ality) unto themselves. But the first thing – the first thing – that Scratch does when the two of them finally have a moment to speak in person is to declare hir biological allegiances:

“Okay,” ze finally said, all the breath pushing out of hir in a whoosh. “I’m a girl, woman, crone, maiden, chick, bitch, cow, dyke, babe, sweet-pea, female person. This week I wanna look like Johnny Depp and last week it was Garbo. I wish I were black because I hate my skin and probably next week being a wolf would be even better.

Ze kept looking down, but the words kept pouring out.

“I’m not afraid to walk down the street alone because I am all those things inside without thinking about it; then somebody calls my name or rather, my sex, and I feel like I’m in a borrowed body, the body I was born into, easily recognizable, to other people, not to me. They want to sculpt it and dress it and reduce it and extend it but it’s worked against me a lot or has had itself worked against.”

“I’m a female,” ze finished in a lower voice that trailed off. “And now my freedom’s over.” […]

“Pushing forty, I started dressing and acting how I felt and realized it’s my life and I’d been wasting a whole lot of time acting like it’s someone else’s.”

Ze paused. “Do you know what happened when I started doing that?” But ze wasn’t really waiting for our answer. “Nothing. Except,” and Scratch started blushing, “I got a whole lot more dates from women.”

For some reason I blushed, too.

“I feel I’m finally in my body,” Scratch went on. “Which is funny because the second I went online I started being in a whole lot of other bodies, too.”

“And how!” Winc said very quietly to hirself, but Scratch heard it and kind of shifted like ze was uncomfortable.25

There’s an interesting thread to draw upon here about the gender-as-performance argument as seen through the lens of plurality. Judith Butler (the feminist theorist responsible for pioneering the performance theory to the mainstream) writes in Gender Trouble a few years after the publication of Nearly Roadkill:

What can be meant by “identity,” then, and what grounds the presumption that identities are self-identical, persisting through time as the same, unified and internally coherent? More importantly, how do these assumptions inform the discourses on “gender identity”? It would be wrong to think that the discussion of “identity” ought to proceed prior to a discussion of gender identity for the simple reason that “persons” only become intelligible through becoming gendered in conformity with recognizable standards of gender intelligibility.26

Butler’s writing style is notoriously unreadable; there are two things in this passage you should note. Firstly, Butler’s problematization of the notion of “identity” presumes the continuity of that identity, i.e. that conventional wisdom assumes that your “identity” will always be the same. Butler then suggests that gender dynamics pose a challenge to notions of stable identity, fracturing the illusion of continuity. This is very much in line with our discussion about how the presence of femme alters in AMAB systems can challenge the notion that the system “has” a stable identity in the first place. But the second issue is perhaps more important: part of the complexity of this issue is that in 1996, neither transness nor plurality constituted “recognizable standards of gender intelligibility” (and plurality still doesn’t). Butler continues by noting that the internal coherence of gender identity in the popular conscience is framed around the heterosexual desire as its congealing force:

Gender can denote a unity of experience, of sex, gender, and desire, only when sex can be understood in some sense to necessitate gender—where gender is a psychic and/or cultural designation of the self—and desire—where desire is heterosexual and therefore differentiates itself through an oppositional relation to that other gender it desires. The internal coherence or unity of either gender, man or woman, thereby requires both a stable and oppositional heterosexuality. That institutional heterosexuality both requires and produces the univocity of each of the gendered terms that constitute the limit of gendered possibilities within an oppositional, binary gender system. This conception of gender presupposes not only a causal relation among sex, gender, and desire, but suggests as well that desire reflects or expresses gender and that gender reflects or expresses desire. The metaphysical unity of the three is assumed to be truly known and expressed in a differentiating desire for an oppositional gender—that is, in a form of oppositional heterosexuality. Whether as a naturalistic paradigm which establishes a causal continuity among sex, gender, and desire, or as an authentic-expressive paradigm in which some true self is said to be revealed simultaneously or successively in sex, gender, and desire, here “the old dream of symmetry,” as Irigaray has called it, is presupposed, reified, and rationalized.27

Butler’s account of gender tends to focus on sexuality instead of transgender experience. I am hardly the first trans theorist to attempt to commentate on the shortcomings of Butler when it comes to conceptualizing the trans self, and honestly, I’m not really interested in wading into that discourse. Some people see themselves in Butler’s work, and others don’t, and I’ve always found it to be somewhat of an immature theoretical stake to attempt to claim that one side is more philosophically or metaphysically “right” than the other. These passages are of primary interest to us because of the way Butler has framed “identity” and “personhood” as a phenomenon which arises only after the subject has gained visible gender in society, a process that begins before birth (think gender reveal parties). What Butler describes here about gender ontology as a matrix of heterosexual desire in the social conscience mirrors really well onto the way that Scratch describes hir former sense of self (where ze tried to escape being female at any cost), and I find that where Butler further takes this argument maps well onto Scratch’s new declaration that each act of gendered non-conformity only makes hir more secure in hir embodied position as a unitary actor.

In this sense, gender is not a noun, but neither is it a set of free-floating attributes, for we have seen that the substantive effect of gender is performatively produced and compelled by the regulatory practices of gender coherence. Hence, within the inherited discourse of the metaphysics of substance, gender proves to be performative— that is, constituting the identity it is purported to be. In this sense, gender is always a doing, though not a doing by a subject who might be said to preexist the deed. The challenge for rethinking gender categories outside of the metaphysics of substance will have to consider the relevance of Nietzsche’s claim in On the Genealogy of Morals that “there is no ‘being’ behind doing, effecting, becoming; ‘the doer’ is merely a fiction added to the deed—the deed is everything.” In an application that Nietzsche himself would not have anticipated or condoned, we might state as a corollary: There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very “expressions” that are said to be its results.28

From a plural lens, there are a lot of problems with this argument. What goes unstated and implicit in this argument is that irrespective of the deed/doer rhetoric as a frame device, the “doer” being discussed here is not a physical doer, i.e. a body, but a metaphysical doer, i.e. a brainstate, a person, a mind. Gender as performativity frames, in a sense, the body as stage; the body is the instrument of performance, the canvas; it underlies, it is the mode of articulation. All that matters is how action manifests upon the body and creates the illusion of an identity underneath.

So when a body’s performance sharply differs after a “switch,” when two alters change who controls the body, gender as performativity does posit that neither action indicates a core identity more than the other! That’s undeniably a step up from the “core self” argument of the 20th Century psychologist. But it leaves a gaping void in its wake. The manifestation of multiple personalities in the world is just that, an “expression” of personality rather than any sort of indication of selfhood. Switching alters is no different from changing your clothes or playing a role in a school play. It’s hard not to see that the one thing which stays “consistent” in this sense is not the doer, not the deed, but the stage of action, the platform, which is nothing more than the body itself. One stage, one continuity of deed – one can only presuppose one actor, or an actor-by-absence, the singular shadow that remains when one possesses no actor at all.

This line of argument becomes explicitly destructive when applied to plural audiences. When alterhood is conceptualized as nothing more than a “performance,” “expression,” or “act,” it puts the onus of deciding whether a person is experiencing DID not upon the person actually experiencing the disorder, but upon the “audience,” whose job thus becomes determining whether the system is a “real” plural system or just “faking” it, an action known in the plural community as “fakeclaiming.” This inspires a truly cataclysmic level of anxiety and self-doubt in the system, which only serves to reinforce their denial and resistance to care. I’ve witnessed the impacts of this mindset firsthand, and let me tell you, it can fuck people up.

The worst part about this is that Butler has a point! So much of how we understand “identity” hinges upon having a stable gender, a legal gender, one given by the state. Those who attempt to exist outside of the framework of socially acceptable gender (like alters) face harsh censure from their peers; it’s not that they don’t have a gender, it’s that society treats them as though they don’t, or as a different gender altogether. The problem arises from the fact that taking an uncritical version of the performativity picture of gender would also demand us to take a fundamentally asocial, even anti-social, definition of how plurality and DID work. Much as gender is an ordering principle beyond systems, it’s also an ordering principle within systems, and can be one of the most critical pieces in the implicit social norms and strictures of headspace. Butler’s analysis is important for unthinking that. But by arguing about the complete ontological lack of an actor, the onus of action itself is subtly shifted from the person to the body, which then becomes held as prior, if not primary, to any sense or articulation of personhood. A Butlerian view is only useful to the plural commentator insofar as alterhood can be articulated from the lens of an internal body, necessarily a mental body, which is definitionally impossible from the same view. This complete erasure of the possibility of intra-system relationships suggests not only that the subject with DID is suffering from “episodes” of “personality shifts,” but also poses that the idea of multiple alters communicating with each other, a basic tenant of plural life, is an act verging on narcissism or schizophrenia. A plural-informed performativity argument could totally argue that gendered performance in headspace should be a critical piece of rethinking system dynamics, but that’s completely impossible in the anti-metaphysical picture of performance forwarded by the Post-Modernist singlet mainstream.

A particularly noxious 1998 article from Anthony Kubiak drives home how easily the Butlerian argument of performativity can be weaponized into pluralphobia:

Soon an ensemble of voices and clashing personalities emerges, a theatre of therapeutike, which replays the events of the trauma. The individual, in other words, now disindividuated, now more collective than unitary, acts in a microtheatre of cruelty within which she both reenacts and prevents the enacting of the trauma that gave her theatre its birth. Taken together, this is what is popularly known as multiple personality syndrome, or multiple personality disorder, now called DID-dissociative identity disorder, the name change ironically recapitulating the shifting, dissociative thing itself. This disorder has a rather short history, and one that is worth recounting briefly here, if for no other reason than to point out that multiplicity, too, has its history (Hacking 1995).29

The “microtheater of cruelty,” as Kubiak so callously puts it, is precisely what I have been trying to isolate and interrogate over the course of this article (and don’t think I’m overlooking the way he assigns “her” as female). He’s right, it is a common problem for people with dissociative issues, but it is hardly a problem without recourse. There’s absolutely no reason that systems need to mirror toxic dynamics of sexism, abuse, violence, and all of the other issues I have here brought to light, but the way that we unthink that is by talking about it, processing, coming up with new tactics and methods for systems to reach healthier equilibriums. But Anthony Kubiak has absolutely no interest or investment in healing those cruelties.

Rather, his “solution” is to question – fakeclaim – whether DID is even a “real” phenomenon in the first place.

Once memories can be recovered through the narratives and words of the various alters, the patients can be reintegrated. Therein lies the second of the great controversies of DID and recovered memory: How does one know, barring outside confirmation, that one’s memories are in fact “true”? Does the import of one’s memories depend on their external confirmation by others, or on the subjective impact they have in forming identity? Further, doesn’t conflating memory and identity in this way obscure the deeper and more difficult problem of subjectivity? And isn’t the multiplication of identities, and the ability to switch identities merely a multiplication and obfuscation of the original problem? If identity-gendered, racial, classed-is decentered and unstable, how does mere multiplication or the ability to switch identity/race/gender change the fundamental problem of identity and subjectivity? How, precisely, is this-as many what I call “new Column” DID sufferers claim-liberatory, or even evolutionarily superior? And finally, even though the pathologies of DID are clearly not what gender theorists have in mind when they question cultural assumptions about the stability of identity, what does DID itself suggest about such assumptions? Might the positing of some hegemonic idea of identity-stability be a straw-man argument? The prevalence of DID might suggest so, as might the currency of multiplicity in movies and TV.30

Ah yes, because obviously the number one reason people are plural is because they want to be “evolutionarily superior.” Kubiak’s distaste for plural people becomes even more evident in subsequent paragraphs:

What, in fact, makes DID unbelievable, or at least arguable, to many observers is its failure, like Finley’s performance, as theatre. While on the one hand many object to the substantive claims of DID because it seems like so much bad acting, many suspicions seem to center on DID’s very insistence on its own nontheatricality, on its “reality.” Thus while the poststructural world continues to present us with theories of the insubstantiality of self, DID is trying, like some gender theory itself, to convince us of the self’s (multiple) reality. Indeed, outside gender theory, experts in consciousness and identity such as Daniel Dennet see multiplicity-as-identity as inevitable, a healthy and predictable response to modern fragmentation. But modern fragmentation and the painful decenteredness of identity has little to do with the indeterminacy of genders or races-it has to do with the suspicion that I might be no-one at all. We are not talking about the “humanist” fear of shifting identity, ultimately, but the fear of non-being, of death.

Corollary to this, what are we to make of the resistance among many in the DID community to reintegration? Many refuse to see themselves as anything other than normal but still wish to insist on the mutual nonresponsibility among alters for any one alter’s actions-if my alter “Bill,” for example, exposes himself to a woman in a hotel room, should my other alters be held responsible for it? It depends, of course, on who is asking the question, one’s therapist or the state prosecutor.’31

The notion that some plural people don’t want to pursue integration because they want to be able to get away with rape is a wild leap – and I can’t help but feel like the author calls himself out by suggesting that his own “alter” would be the rapist. What would be his alter’s full name, Bill Mills? Similarly, this notion of a “failure to theater,” i.e. the idea that it’s the system’s job to convince singlets of their personhood, and that a failure to do so is sufficient grounds to take DID as an “unbelievable” disorder, reads in so many shades of the Real Life Test for trans women. If you can’t jump right into the deep-end of full-time girlmoding, if you can’t pass as a cis woman before you even begin to transition medically, then are you even a woman? And this idea that systemhood is a manifestation of a nihilist fear of oblivion – that’s just not comprehensible to me. Most systems struggle with having too much selfhood going on in their brain, not a void thereof. The verbiage of “theater” or the “therapeutike” used in this article are, I think, just hollow shades of the rhetoric of the trial, just as Kubiak’s imagined plural subject is quite clearly a failing wannabe of Billy Milligan (literally) and the position of the singlet theorist stands as judge, jurist, and executioner supreme.

Let’s bring our argument back around to Scratch and Winc. What’s so striking about this scene is that these two characters, who have appeared so very similar for the whole book, suddenly show up as wildly different people the moment they come together in person. Scratch is in many ways the ideal provocateur of a Butlerian gender trouble – through performance, through a rejection of ontological womanhood, everything ze does on the internet only increases hir comfort with using hir body as a stage. By contrast, Winc represents a certain failure to see gender through a performative lens. Winc has spent the entire first half of the book investing a certain level of selfhood into not just hir own characters, but Scratch’s characters too. It’s not just who hir wants to be or chooses to perform, it manifests in some crucial way who ze is. And this brings up one of the key flaws with this paradigm – on some level, gender-as-performativity is framed as an ethical paradigm, not just a metaphysical one.

If the body is the stage for the disembodied performance of gender, the medium, the paintbrush, then Winc’s attempts to use hir chatlogging and criminal cybersexing to escape that (dyphoric, transfeminized) body becomes not just a failure to actually perform gender, presupposedly the thing that ze’s best at, but an actual ethical shortcoming, a social deficit that Winc must now apologize to Scratch for. It was all a masquerade for Scratch – but not for Winc.

Never for Winc.

Normally in transfeminine fiction, one of my least favorite tropes is when the author interrupts the flow of the novel to infodump about medical or social transition for several pages, but I think it works in Nearly Roadkill because it nails home how Winc suddenly has to extensively prove and explain hirself – hir real-world self – to Scratch to maintain their relationship. Scratch opens hir email to Winc with “I love you, I want to be with you somehow, but the words are still fucked up, I have questions that are stupid but I have to ask them of *somebody.*”32 What ensues: Winc explains to Scratch what it’s like to be a non-binary transfemme, Scratch explains to Winc what it’s like to be a dyke, they’ve talked their shit out, they’re on a level-playing field again.

This conflict may have played out through the late-90s lens of performativity, but this rupture hints at a more fundamental truth about human subjectivity and our inability to conceptualize plurality or transfemininity on the societal level. Butler’s philosophy is so persuasive because it is hard for us to conceptualize or perceive the interiority of other human beings. It’s tempting, almost sexy, to think that we as people could be nothing more than how we display ourselves. There’s a post-modernist panache to the concept. But I don’t think that performativity changes the presumption of a subjective representation of personhood, just dislocates it into the eyes of the audience. Both Scratch and Winc expected the other to perceive them in the same way as they perceived themselves, and when there was a mutual failure for that to happen, it caused a serious rupture in their relationship, and societal power dynamics immediately took over.

In the performativity model of gender expression, theatrical expressions of gendered selfhood are privileged, and private notions of gendered ontology are called into question, challenging the idea of a heterosexist gender conformity as the primary metric for establishing a gendered identity. But when selfhood is hidden/withheld by necessity (transness) or by design (plurality), the silent trans plural subject is erased by their failure to show up as “trans” or “feminine” or to exhibit “multiple personalities” before the masses. This is further exacerbated through the creation of systems (read: DSM-III) which directly punish overt expressions of plural transfemininity or genderqueer alterhood. The lack of action or paralysis this produces can then be read as “proof” that the trans plural subject was “faking it” all along, and used to write off their subjectivity (that classic tactic of domination) in the process. This overt erasure of the bodily potential of the alter in headspace – i.e., the impossibility of gender identity for the subject dissociated from their body – is a bioessentialist paradigm, a product of the supposition of flesh, either gendered or not. There’s a reason that plural folks sometimes call singlets “meat people” – the condition of existing within a system of multiples has an alienating effect upon one’s ability to claim embodiment on several levels, both within and without. Even the trans woman singlet, even the enby can on some level describe their gendered self through a relationship to embodiment. But when the alter has been rendered disembodied and fragmentary, she loses the verbiage to describe the ways that her social condition still reflects embodied hierarchies of domination and subordination within the confines of her ephemeral mind. Even when you’re fronting, even when you have access to a physical body, that alienation still lingers with a vengeance.

Now is an important moment to recall that the cause of Dissociative Identity Disorder is severe abuse of a physical, sexual, emotional, verbal, or neglectful nature experienced from a very young age. That is an active violence which produces this condition within the child, an active force of malice that provides the conditions for this alienation. Alters aren’t just affected by these hierarchies of subordination and domination – they’re often their worst victims.

And we wonder why people who fall under the transfeminine umbrella struggle so chronically with dissociative issues.

I’m reminded of this passage from Eduardo Nicol about the problematic of consciousness: